December 9, 2025

SEOUL – The English portion of this year’s College Scholastic Ability Test, or Suneung, saw its smallest pool of top scorers since absolute grading was introduced in 2018, raising fresh doubts over whether Korea’s exam system can ever truly reduce its reliance on private education.

According to data released Friday by the Ministry of Education, only 3.11 percent of test-takers earned Level 1 — a score of 90 or above out of 100. Under what officials consider an “appropriate” difficulty level, roughly 7 percent of students typically achieve the top grade.

This year’s proportion is the lowest since 2018, when the English section shifted from relative to absolute grading as part of a government push to curb excessive competition and reduce private education spending.

Education experts argue that the Korea Institute for Curriculum and Evaluation has failed to meet that goal.

“They ultimately failed in controlling the exam’s difficulty, even though they had the best experts convene to create the questions,” the Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education told The Korea Herald.

Although the city’s education office acknowledged that the record difficulty in this year’s English section could draw students and parents toward private education, they warned it was not a new phenomenon and the absolute grading system was not to blame.

“This can happen in any subject. In the long run, we must move away from this multiple-choice-centered exam.”

Concerns run deeper outside Seoul, where access to private academies is far more limited.

“The purpose of the absolute grading scale is to allow students to prepare for college entrance with public education alone,” said an official at the Gwangju Metropolitan Education Office. “If we do not strengthen public education, students in rural areas — who already lack access to private education — will be at a disadvantage.”

Regional breakdowns of Level 1 scorers have not yet been released. But one high school in South Jeolla Province reported that none of its 74 students received a Level 1 score, deepening worries that many students will not be able to meet the minimum score for early admissions.

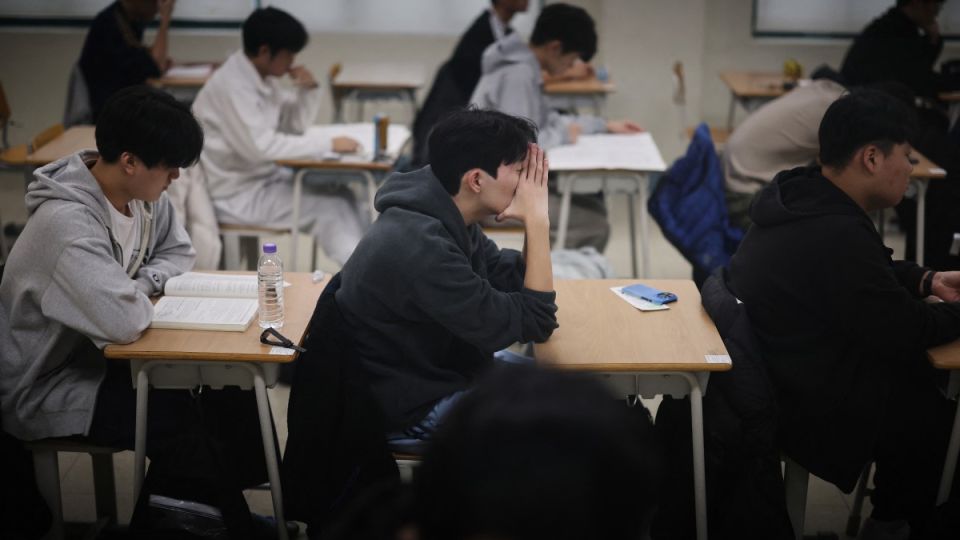

The unexpected difficulty is also fueling anxiety among parents, many of whom now feel pressured to expand their children’s enrollment in private academies.

“Which private academy should I send my 11th grade daughter to? She usually gets Level 1 in mock exams,” wrote a parent on DSchool, an online community for parents. “We’ve been focusing on math and science, but after seeing this year’s Suneung results, I think she needs English classes too.”

Another parent wrote: “Only 3.11 percent of students got Level 1 in the English section. This shows we can’t overlook English when choosing private academies.”

Local private academies are already seeing an uptick in inquiries.

Kim Joo-hyung, deputy head of Gwangju Daeseong D-Quantum, told Yonhap News Agency that “even top-performing students unexpectedly received lower grades in English and failed to meet minimum admission requirements,” adding, “We’ve been getting consultation calls since the score reports were released on the Friday.”

KICE Director Oh Seung-geol also issued a rare statement acknowledging the issue, saying he “regrets” that the test failed to meet its intended purpose of evaluating students’ mastery of the curriculum under an absolute grading system. He added that KICE would aim for a 6-10 percent Level 1 rate when setting future exam directions.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Education announced Friday that it would conduct “a comprehensive investigation” into KICE’s test-making process in December.

The country’s top education authority conducts routine inspections after each year’s college entrance exam. The Education Ministry said it would use this channel to determine why KICE failed to manage the difficulty level and identify areas for improvement. The review is set to begin in December.

Still, education officials emphasize that the challenge extends beyond English — and that an overarching overhaul on the testing system is necessary.

“This year’s English results do not mean the absolute grading system itself is flawed,” a Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education official said. “This nine-tier relative grading system makes students constantly compete. It is our stance that we should move toward the absolute grading system for other subjects.”

“We need to keep the (absolute) system (in English) so students feel less burdened by the Suneung, and expand university admissions criteria to better reflect diverse school activities.”