August 1, 2022

TOKYO – From heads of state to ordinary citizens, people from all walks of life make their thoughts known through social media, which has become a vital tool for expression in modern society.

Currently, the deletion and monitoring of postings remain the responsibility of the platform operators that manage social media.

But a battle is raging over transparency and accountability on these platforms.

In February last year, Masato Fujisaki, 38, a part-time university lecturer who writes a column for a magazine, was stunned to receive a notice from Twitter saying that due to an allegation of copyright infringement, his account had been frozen.

He could not open his Twitter account, and had no idea what he had done.

But reading between the lines of the notice and Twitter’s regulations, he determined that the image of a brand-new travel bag he had posted a few days earlier had been a DMCA violation.

The DMCA is the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which took effect in the United States in 2000.

The act exempts social media companies from legal liability as long as they remove postings claimed to be copyright infringements.

Twitter has been freezing the accounts against which the claims were made, without being required to verify the authenticity of the allegations.

There have been many cases in which this situation was exploited, with someone filing a false claim of copyright infringement to purposely get another person’s account frozen. Fujisaki was the victim of such an act.

His account was unfrozen four days later. Presumably the fake allegation had been withdrawn, but Twitter offered no explanation beyond the initial notice.

“The person making the fake report is the bad guy, but I find it unacceptable that a place for discussion and commentary can be taken away without explanation,” Fujisaki said indignantly. “It is also strange that we are being affected by U.S. law.”

Responsibility for disclosure

In many developed countries including Japan, the removal and monitoring of harmful information is left up to the discretion of platforms such as Twitter and Facebook.

This is because some harmful information is not necessarily illegal, and legal restrictions could infringe on freedom of speech.

Twitter freezes 1.5 million accounts a year worldwide, and Facebook deleted 95.5 million posts last year for slander and hate speech alone. That said, neither company has ever disclosed how they monitor information and other regulatory factors.

This stance is facing criticism in Japan as well. In February of this year, the Internal Affairs and Communications Ministry’s council examining platform services held an online meeting with employees of platform operators.

Pressed by council members to disclose the number of staff members tasked with monitoring postings in Japan, “We cannot say because of safety issues with our staff” was a common response.

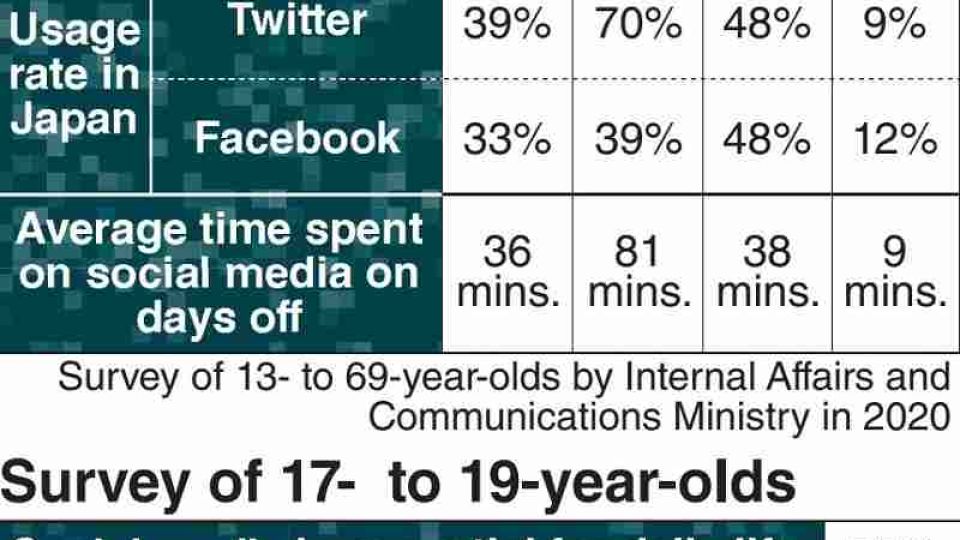

Twitter and Google refused to even disclose the number of users in Japan. That drew a strong rebuke from Ryoji Mori, a lawyer on the council, who said, “As long as they do business in Japan, they have a responsibility to disclose information.”

Facebook’s ‘Supreme Court’

In the face of snowballing criticism, Facebook has finally begun to move toward greater transparency.

The company established an Oversight Board to review appeals from users, and in May last year announced 20 experts from Europe, the United States and Asia who would serve on it.

It has been dubbed a “Supreme Court” because it has the power to overturn Facebook’s decisions.

In January, the board announced the results of its first review, in which it invalidated four of five cases of deletion.

It ruled that criticism of France’s measures against the novel coronavirus and images of women’s breasts to raise awareness of breast cancer were not violations of the rules.

Kuniko Ogawa, director of the division in charge of consumer policy at the ministry, keeps a close eye on the moves of platform operators.

“If they continue to be reluctant to disclose information, the movement to force accountability through laws will grow around the world,” Ogawa said. “We are at a crossroads right now.”