March 14, 2023

MANILA —The Philippines still lagged in the latest Safety Perceptions Index (SPI) despite improving 16 places to 112th out of 121 countries compared to last year’s 128th.

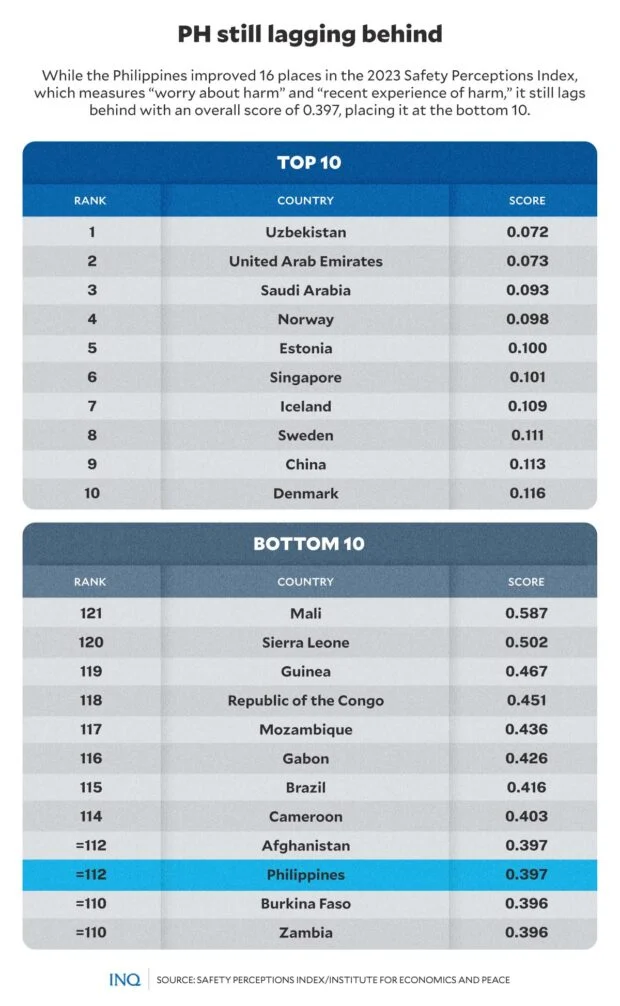

Based on the SPI, which is produced by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) to provide a “comprehensive assessment” of worries about and experiences of risks across 121 countries, the Philippines had an overall score of 0.397.

The 0.397 even exceeded the global average of 0.2376, making the Philippines one of the countries with the highest scores. As explained by the Lloyd’s Register Foundation (LRF) and IEP, a score closer to 1 indicates a higher level of risk impact.

With the Philippines at the bottom 10, or the countries with the highest scores, were Mali (0.587), Sierra Leone (0.502), Guinea (0.467), Republic of Congo (0.451), Mozambique (0.436), Gabon (0.426), Brazil (0.416), Cameroon (0.403), Afghanistan (0.397), Burkina Faso (0.396), and Zambia (0.396).

As the LRF said, Mali, which is suffering from a “violent internal conflict” and saw its government overthrown in successful coups in 2020 and 2021, is the most risk-impacted country, while Uzbekistan, which had a rate of 0.072, is the least.

With Uzbekistan in the top 10, or the countries with the lowest scores, were the United Arab Emirates (0.073), Saudi Arabia (0.093), Norway (0.098), Estonia (0.100), Singapore (0.101), Iceland (0.109), Sweden (0.111), China (0.113), and Denmark (0.116).

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

“The past several years have been characterized by rising feelings of uncertainty worldwide. Central to this shift has been the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted the functioning of social institutions as well as patterns of individual and collective behavior in countless ways,” the LRF said.

PH most concerned about severe weather

The SPI did not indicate the overall score that the Philippines got in each of the five domains being analyzed to measure people’s worries and experiences of serious risks, but it stressed that the country is one of the most risk-impacted when it comes to severe weather-related events.

As the LRF said, there are five domains in the SPI—food and water, violent crime, severe weather, mental health, and workplace safety—which broadly cover threats related to health, security, and the social and physical environment.

“While these domains are not an exhaustive collection of all risks, they do cover those that people are likely to face in their daily lives and that could result in serious harm,” it said.

Based on the SPI, which was released last month, it is severe weather that the Philippines is most worried about, especially since its experience rate of that risk is the highest among the 121 countries included in the Index.

The Philippines, the LRF said, has an experience rate of 62.4 percent and a worry rate of 67.1 percent, making it second only to Mali as the most risk-impacted by severe weather-related events.

It was explained that severe weather-related events, and violent crimes, too, “are likely to be associated with high levels of unpredictability and uncontrollability [so] it is therefore unsurprising that worry for these two domains tends to show the highest absolute levels of worry and the highest relative levels of worry in comparison to first-hand experiences.”

Setbacks from extreme weather events

But why is the Philippines most worried about severe weather-related events that it even landed in the top 5 countries, which includes Mali, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Burkina Faso, that are most risk-impacted?

Though the LFR did not indicate the reason, recent assessments have presented how extreme weather events could inflict a heavy toll on the Philippines, which has been considered the “most disaster-prone country” in the world.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

Even in the latest Global Risks Report that was released by the World Economic Forum last Jan. 11, it was stressed that in the next two years, natural disasters and extreme weather events will be the top risks for the Philippines.

Based on data from the Philippine Atmospheric Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (Pagasa), close to 20 typhoons are entering the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) every year.

Last year, Souleymane Coulibaly, lead economist of the World Bank, said climate change, which manifests itself through rising temperatures, increasing sea levels, more intense droughts and stronger typhoons, will significantly threaten the global economy.

He said without interventions from the government and private institutions, extreme weather events will likely slash gross domestic product by 13.6 percent by 2040 and inflict a heavy burden, especially on the poorest of the poor.

Coulibaly said the consequences of climate change are expected to negatively impact economic growth as it is seen to erode natural and physical capital, lessen work productivity, weaken financial stability, and alter domestic and external competitiveness.

This, as “temperatures in the Philippines will continue to rise by the end of the 21st century,” while “rainfall patterns will change and intensify, and extreme weather will become more frequent.”

Intensifying climate change

As Pagasa said, while typhoons hitting the country are becoming fewer, those that do make landfall are becoming stronger. Out of the average 20 typhoons that enter PAR every year, eight or nine make landfall.

“Based on our data, we have seen that the frequency of typhoons is decreasing a bit and we have seen that for those greater than 170 kilometers per hour, there is a slight change, there is a slight increase,” it said.

Likewise, Pagasa said it was expecting the country’s temperature to rise by four degrees by the end of the 21st century, while the intensity of typhoons that make landfall will continue to increase.

As scientists had stressed, warmer temperatures, which melt ice caps and cause oceans to expand, was the reason that sea levels are rising.

Take the case of the sea level rise in the Philippine Sea, which Pagasa climate scientist Dr. Marcelino Villafuerte said had risen by about 12 centimeters, or about 5 inches, over the past two decades.

Pagasa said the sea level in the Philippines is rising 3 times faster than the world average. With 70 percent of its municipalities facing large bodies of water, including the Pacific Ocean, the rise could spell a “big impact” on millions.

Based on a study by the International Food Policy Research Institute, climate change is expected to put 2 million more people at risk of hunger by 2050 and cost about P145 billion every year.

Rise in ‘ambiguous risk’

As the LRF said, there were two central findings in the 2023 SPI, and one of those points to a notable rise in generalized and non-specific feelings of fear and lack of safety throughout the world, with people becoming more fearful overall but less certain about the sources of potential threats.

It stressed that the Index found a rise in “ambiguous risk,” which refers to people’s sense that risk exists in the world around them but that it cannot always be defined.

“The rise in ambiguous risk can be seen in the responses to a World Risk Poll question on the greatest perceived threat in people’s daily lives,” the LRF said.

“Between 2019 and 2021, the largest changes in response rates were for those saying that no risk existed in their lives, which fell by half, and those saying they did not know what their greatest risk was, which nearly doubled.”

It said this year’s SPI highlights the changing dynamics of risk that accompanied the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic as the world became less certain about its future than at any time since the Cold War.