January 5, 2026

SINGAPORE – One of the biggest surprises in 2025 has been the resilience of world trade. Front-loading in anticipation of US President Donald Trump’s punitive “America First” tariffs helped allay concerns about a collapse in volumes.

But this certainly will not be enough for 2026, the second year of the second Trump administration. The World Trade Organisation in October sharply downgraded its forecast for global merchandise trade growth in 2026 from a previous 1.8 per cent to 0.5 per cent.

The US’ waning appetite for global leadership is spawning levels of uncertainty and unreliability that many countries are unaccustomed to navigating, in areas as wide-ranging as trade and security.

With their economies intertwined with the world’s two largest economies, South-east Asian nations are finding out just how difficult it is to strike a balance in satisfying one without jeopardising relations with the other. Several nations are still embroiled in complex negotiations with the Trump administration over their respective bilateral trade deals.

China’s projected trade surplus of more than US$1 trillion (S$1.29 trillion) with the rest of the world remains one of the biggest challenges for the global economy.

And then there’s security and defence.

Mr Trump’s demands for US allies to raise their individual defence spending have reignited Europe’s erstwhile dormant military industries, even as worries grow about a looming arms race in Asia after the Chinese and the Americans changed their tone on North Korea’s denuclearisation.

In an era where geopolitics plays an outsized role in determining economic realities in a multipolar world, middle powers and small states are having to innovate and redefine priorities just to survive.

Will a weaker Trump be good for Asia?

While growth has indeed materialised in US President Donald Trump’s first year in office, job creation has slowed and Americans are disappointed by the rising cost of daily essentials, housing and healthcare. ILLUSTRATION: THE STRAITS TIMES

Only two US presidents have seen their party expand House seats in a midterm election since World War II: Mr Bill Clinton in 1998 and Mr George W. Bush in 2002. Will Mr Donald Trump join that exclusive club?

It does seem difficult. The economy is the crucible in which all presidents are tested, and trends do not favour him.

In Mr Trump’s telling, he is transforming the “dead” economy he inherited from his predecessor. Tariffs are generating billions in revenue and trillions in investment commitments, and reviving the US’ industrial base. His tax cuts, deregulation and support for domestic energy production are all energising the US economy.

But while growth has indeed materialised in Mr Trump’s first year in office, with wages rising and petrol prices falling, job creation has slowed and Americans are disappointed by the rising cost of daily essentials, housing and healthcare. His starkly low job approval ratings (36 per cent, according to Gallup) say it all.

What’s more, the Supreme Court could in January strike down the legality of roughly half of his tariffs imposed under emergency powers.

Will voters be dissatisfied enough to punish the Republicans in the Nov 3 midterm elections?

Mr Trump is, of course, not on the ballot. But he is the only important national figure on the horizon, and the prime target for Democrats. They will paint him as an out-of-touch lame duck pre-occupied with ballrooms and golf courses and tainted by his connection to convicted paedophile Jeffrey Epstein.

Six by-elections in 2025 delivered a 15-point swing to the Democrats. Factoring in gerrymandering, the likely outcome is that the House shifts from a slight Republican majority to a slight Democratic one.

That would hobble Mr Trump.

“A weaker Trump probably means a foreign policy less about who Trump gets along with and more about inputs from Congress and advisers,” said Mr Joshua Kurlantzick, a senior fellow on South-east Asia and South Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations.

For Beijing, is a chastened Mr Trump a threat or a respite? At least four Trump-Xi meetings loom in 2026, including state visits.

“Trump is personally not committed to the hard policy towards China that Washington has pursued over the last eight years. Expect stability at least until his Beijing summit in April,” said Professor Robert Sutter of the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University.

Mr Trump’s soft-on-China and hard-on-allies policy will almost certainly invite greater scrutiny.

If the Democrats gain in November, Prof Sutter added, they will attach values such as human rights, democracy and the rule of law to foreign policy.

But in the meantime, allies like Japan, South Korea, Australia and quasi-ally India will stiffen at the spectacle of Washington cutting a deal with Beijing at their expense. The quiet hedging away from the US and the build-ups of defence and mini-laterals will continue.

South-east Asia, too, will adjust its sails. – Bhagyashree Garekar

What are the prospects for a China-US ‘grand bargain’?

Analysts say face-to-face meetings between Mr Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping will be pivotal in shaping not just the trade war, but China-US relations more broadly, in 2026. ILLUSTRATION: THE STRAITS TIMES

The thunder was loud, but the rain is light. This Chinese idiomatic expression frames how many in China remember the way US President Donald Trump waged his trade war against China in 2025.

When Mr Trump returned to office in January, he shocked the world with his audacious Liberation Day tariffs. An exhausting ding-dong with the US saw tariffs on Chinese goods surging, stalling and eventually shelved. Even at their peak, the apocalyptic triple-digit levies lasted barely a month.

At the dawn of 2026, bilateral restraint appears likely, since Washington is keen to make Mr Trump’s planned April visit to China happen.

The signs are clear. On Dec 23, the United States announced fresh tariffs on Chinese semiconductor imports, but postponed their implementation until June 2027.

Behind the scenes, White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller has been tasked with ensuring that no government department does anything to upset the tenuous detente.

The shift was also echoed in the tone of US State Secretary Marco Rubio at his year-end press conference, where he recast China as a powerful constant rather than an existential rival.

“If even China hawks like Rubio are changing their tune, it shows the US is determined not to let ties sour before the April visit,” said Mr Wang Zichen, a research fellow at the Centre for China and Globalisation.

This truce may even extend till the end of the year, with further opportunities for the leaders to meet when China hosts the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit, and the US hosts the Group of 20 summit.

Analysts say face-to-face meetings between Mr Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping, two leaders with outsized influence over their countries, will be pivotal in shaping not just the trade war, but China-US relations more broadly, in 2026.

Both the US and China have strong incentives to keep trade flowing.

In a crucial US election year, voters are increasingly blaming tariffs for high prices, and Democrats have seized on affordability as their main line of attack. With his approval ratings falling and midterm elections looming, Mr Trump may have little appetite for soaring inflation.

China faces the opposite problem: deflation. Tariffs strike at the heart of its export-led growth model. Although Beijing pulled off a gravity-defying feat in 2025, running a trade surplus of more than US$1 trillion by offsetting weaker US demand with sales to Europe and South-east Asia , economists doubt this can last.

China wants to lean more on domestic demand, but consumers, spooked by shaky job prospects, a property slump and thin welfare support, are understandably reluctant to splurge.

Fruitful Xi-Trump meetings can deliver benefits beyond trade.

Ms Guo Shan of Hutong Research said China could promise more investments in the US, heeding Mr Trump’s call for onshoring. And if US markets were to wobble in 2026 – with the exit of Federal Reserve chief Jerome Powell, for example – China could buy more US Treasury bonds, as it did during the 2008 financial crisis.

Analysts are divided over whether Taiwan could feature in a broader “grand bargain” that goes beyond trade, investment and finance.

Some speculate that China might dangle economic concessions to entice Mr Trump to acknowledge its assertions over Taiwan. Others argue that the issue is too sensitive to be reduced to a bargaining chip for either side.

Moreover, after trading blows in 2025, Washington and Beijing now see their own and each other’s choke points more clearly. This is also likely to lead to restraint.

Both are racing to close vulnerabilities, from rare earths in the US to advanced chips in China. But neither can be fixed overnight.

As long as those dependencies remain, both sides will be compelled to keep relations calm on the surface, even as the frantic paddling to build alternatives continues underneath. – Yew Lun Tian

Whither ASEAN?

For critics of ASEAN, the situation in Myanmar, the South China Sea impasse and now the festering conflict on the Thai-Cambodian border point to its inefficacy as a regional grouping, hindered by its principles of consensus and non-interference.

They point to the limits of ASEAN’s conflict management mechanisms when member states slide into confrontation.

The ongoing conflict between Cambodia and Thailand – in the face of ceasefire agreements facilitated mainly by outgoing ASEAN chair Malaysia and its prime minister, Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, China and the US – has been a strain on the grouping’s credibility. The sporadic violence violates ASEAN’s principles of the non-use of force and the peaceful resolution of disputes.

“There are more than a few things that ASEAN does and does well. Intervening in war once it has started is not one of them,” said Associate Professor Simon Tay, chairman of the Singapore Institute of International Affairs.

“The group has no experience and has no power or clear mandate. Globally, threats to international peace are to be resolved by the UN Security Council and the great powers,” he added.

“I am therefore mystified why some, including so-called experts, demand ASEAN step in to the conflict between Thailand and Cambodia. Under Malaysia’s chairmanship, the group has already done more than it has in its past,” said Prof Tay, who also teaches international law at the National University of Singapore.

“We know the war negatively impacts ASEAN standing, and can rue the cost. But there needs to be wisdom to recognise the difference between what we can hope for and what we can do. Over-expectation and over-reach can be even more destructive.”

For every critical voice, though, there is a chorus of cheerleaders touting ASEAN’s quiet diplomacy and its convening powers in a year of geopolitical upheaval, providing a major platform where the major powers engage with the region and one another.

More recently, supporters have been particularly loud about ASEAN’s successes in economic cooperation, particularly the lowering of trade costs. In 2025, Asean and China inked an upgraded free trade agreement (FTA) , which added to other FTAs with Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, India and Hong Kong.

Such pacts assume greater importance at a time when the Trump administration has slapped punitive tariffs on nearly every country in the world in its “America First” trade policy.

So technically, this should have been the time for ASEAN to shine. Instead, with the Trump administration eschewing multilateralism and preferring bilateral deals, member states have been forced to negotiate separately, vanquishing the hope of any collective bargaining power.

ASEAN member states, along with other countries, appeared to be playing a game of one-upmanship, rushing to the US capital to negotiate – with some even publicising on social media video clips of their calls with President Trump.

Meanwhile, the negotiations and haggling with Washington will remain a constant feature and key risk, with some South-east Asian nations still locked in complex negotiations.

Beijing has reportedly pushed back hard on the deals that ASEAN nations are working out with the Trump administration, alert to how the US could use these deals to curtail the economic and technological access China needs for its ambitions.

The implications for ASEAN are stark. Intense China-US competition is pressuring South-east Asian nations to choose sides. Cambodia and Laos are heavily reliant on China for economic growth, while the Philippines regularly looks to the US for security assurances in the face of Chinese belligerence in the South China Sea.

The way China stepped out of its previously quiet diplomacy in publicising a meeting that Beijing convened between the foreign ministers of Cambodia and Thailand in Yunnan is testament to its desire to deepen its influence in South-east Asia.

But the tussling between the great powers in the cradle of South-east Asia could eventually make it more difficult for ASEAN to form any consensus or united position on any given issue, and erode group cohesion in the process.

Several ASEAN member states are already possibly hedging their positions in moves that could further compromise the centrality of ASEAN.

Indonesia became the first full BRICS member from the group in 2025 after Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam were made “partner countries” in 2024.

The idea that the Trump administration’s rapid retreat from global leadership has spurred a resurgence in regionalism and greater cohesion in ASEAN is therefore at best a partial truth and reality for many.

So even if ASEAN’s supporters urge member states to acknowledge its limitations and work within them, shifting geopolitical realities are bound to intensify doubts over the grouping’s effectiveness and purpose in a new global political order. – Clement Tan

Is a South China Sea code of conduct feasible?

President Ferdinand Marcos Jr wants to finalise the long-delayed South China Sea Code of Conduct (COC) between ASEAN and China by the end of

the Philippines’ chairmanship of ASEAN in 2026. Even then, enforcement may prove contentious.

Despite numerous encounters with Chinese vessels, Mr Leonardo Cuaresma’s community of fishermen continue to make for Bajo de Masinloc, known internationally as Scarborough Shoal. The 150 sq km coral atoll is an important fishing ground contested by several countries.

“Today, Masinloc fishermen can’t enter the shoal. Chinese ships are there 24/7,” said Mr Cuaresma, a community leader and president of the New Masinloc Fishermen’s Association. On some days, he said, China Coast Guard vessels sail as close as 30 nautical miles from Masinloc’s shore.

Forced to retreat into municipal waters closer to shore, the fishers find that their catches are now smaller and competition is tighter, resulting in a quiet economic squeeze on fishing communities that rarely features in diplomatic talks.

Mr Cuaresma believes a written framework still has value, but his deeper concern is enforcement.

International law already provides a basis for accountability, including the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling that invalidated Beijing’s sweeping claims over almost all of the South China Sea. But Beijing has unequivocally rejected that ruling , so violations continue, with no clear mechanism to hold offenders accountable.

Mr Cuaresma does not expect open conflict. He sees China’s actions less as preparation for war than as sustained coercion. “I know they’re not ready to go to war either. They just want to bully us,” he said.

Fishing communities in Zambales are adjusting. They are working with the provincial authorities to support maritime monitoring efforts meant to complement state patrols, with fishermen acting as observers who relay information to the Philippine Navy and coast guard.

But the initiative remains a work in progress, with boats, equipment and systems still some time away from full installation. The expanded community-based monitoring effort is expected to begin in early 2026.

Whether the COC is finalised by end-2026 will depend on negotiations far from Masinloc, but Mr Cuaresma’s concerns point to a more fundamental issue of Asean’s effectiveness.

Even if an agreement is finalised, would it affect behaviour at sea, or will coastal communities continue to bear the cost of the gap between rules and reality? – Mara Cepeda

Why are South-east Asia’s ‘abang-abang’ stepping up on Gaza?

Indonesia and Malaysia have reframed themselves as decisive actors whose moral arguments, backed by organisation, diplomacy and persistence, can attempt to shape outcomes. ILLUSTRATION: THE STRAITS TIMES

Indonesia and Malaysia have stepped into Gaza’s rubble and made their voices heard. Long regarded as the “abang” of South-east Asia – elder brothers whose size, population and confidence shape the region – the two Muslim-majority giants are testing whether moral authority can translate into real-world influence.

In January 2025, Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto met Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim beneath the gleaming Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur. They framed Gaza not as a fleeting tragedy but a decades-long commitment, stressing that moral and humanitarian leadership is not optional but essential.

By July, their meetings had grown sharper and more pointed. In Jakarta, the leaders demanded global collective action for a permanent, unconditional ceasefire.

They condemned the use of starvation as a weapon when Israel blocked humanitarian aid, and celebrated the growing international recognition of the state of Palestine. They also pushed for pre-1967 borders with East Jerusalem as the Palestinian capital, signalling that a just resolution was both urgent and attainable.

In a forceful address to the United Nations General Assembly in New York on Sept 23, Mr Prabowo declared that Indonesia would recognise Israel only if it acknowledged Palestinian statehood. He later offered 20,000 peacekeeping troops – a concrete pledge from one of the world’s largest contributors to UN missions.

Mr Anwar backed a humanitarian flotilla to Gaza , a gesture resonating deeply with Malaysians for whom the Palestinian cause has long been a moral duty. At the Asean Summit, he reinforced Malaysia’s commitment to consistent, principled engagement on humanitarian crises across the region.

Why Gaza? Critics point to other crises – the Rohingya in Myanmar and Uighurs in Xinjiang. While these have not been recently in the spotlight, neither country has abandoned the issues. Both press for Rohingya protection at ASEAN meetings, and Malaysia hosts large refugee communities, while Indonesia nudges Myanmar towards regional peace plans. On Xinjiang, engagement is careful but ongoing, reflecting the delicate balance between moral obligation and strategic ties with China.

Indonesia and Malaysia juggle multiple responsibilities, each shaped by political sensitivities and diplomatic limits. And Gaza draws the most urgent attention and outrage.

It taps into decades of collective memory, religious solidarity and a sense of global injustice. Bombed neighbourhoods, civilian deaths and images of destruction broadcast daily demand a loud response.

For decades, Middle Eastern states and Western powers dominated global Muslim affairs. South-east Asia barely registered. Now, Indonesia and Malaysia have reframed themselves as decisive actors whose moral arguments, backed by organisation, diplomacy and persistence, can attempt to shape outcomes.

Their engagement is no longer abstract; it is measured in troop deployments, humanitarian convoys and speeches that reverberate across continents, signalling that South-east Asia will not remain on the sidelines.

In 2026, the test is clear: Stay loud on Gaza, steady on the Rohingya and Uighurs, and act. South-east Asia’s abang-abang are finally stepping up. – Arlina Arshad

How much is too much in Japan’s push to rearm?

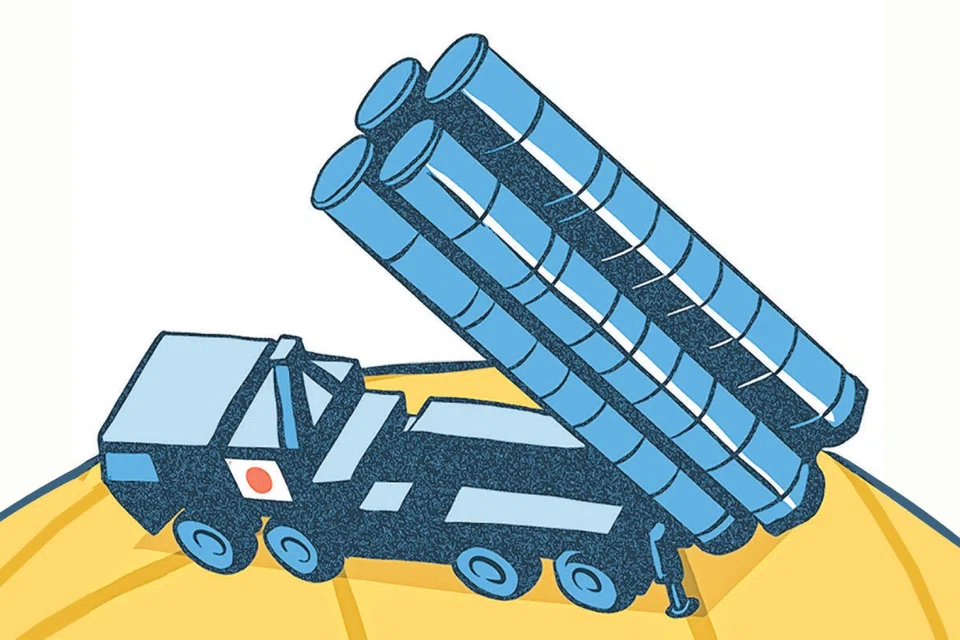

Japan will deploy weapons that can hit adversaries on their own soil for the first time since 1945. ILLUSTRATION: THE STRAITS TIMES

The porcupine will grow its quills in 2026, a defining year for Japan’s security policy as it refreshes a calculus that has long been defined by passive pacifism.

Japan will devote nine trillion yen (S$73.9 billion) – a record in its initial budget – in fiscal 2026 to defence, with plans to buy hypersonic guided missiles with maximum speeds more than five times the speed of sound, deploy long-range missiles and procure drones.

It will also revise the three security-related documents that define its security identity by end-2026 – one year ahead of schedule – and plans to unveil its first-ever defence industry strategy to enhance the resilience and profitability of domestic defence manufacturers.

Also significantly, Japan will deploy weapons that can hit adversaries on their own soil for the first time since 1945. These counterstrike capabilities – approved in 2022 – aim to boost deterrence by thwarting enemy ambitions of lobbing missiles at Japan.

Japan is, after all, surrounded by ideological nemeses and perceived security threats – China, North Korea and Russia – and is deeply unnerved by how the three countries are cosying up to one another. Also concerning is how its security ally, the US , is proving to be nakedly transactional and worryingly unreliable.

Such developments have given Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi and her defence chief, Mr Shinjiro Koizumi, the tailwinds to do more and spend more.

Though this will involve some clever accounting, Japan has declared that it will hit its target of spending 2 per cent of GDP on defence by March 2026 – two years ahead of schedule. The US, however, is pressuring Japan to go even further and spend 3.5 per cent of its GDP on defence.

Despite the looming spectre of higher taxes, 62.8 per cent of Japanese support plans to accelerate defence spending, a joint survey by the Sankei newspaper and Fuji News Network showed in November.

Dr Yasuaki Chijiwa of the National Institute for Defence Studies, pointing to the urgency of growing capabilities in both traditional and new domains, told The Straits Times: “To build up a dynamic and multi-domain defence force, we must have solid financial backing.”

While critics worry that the muscular posture invites the very conflict Japan seeks to deter and risks sparking an unrestrained arms race in East Asia, the risk calculus has flipped for Japan’s defence planners.

The dangerous choice, to them, is not arming up but standing still. – Walter Sim

Is North Korea’s denuclearisation still a goal?

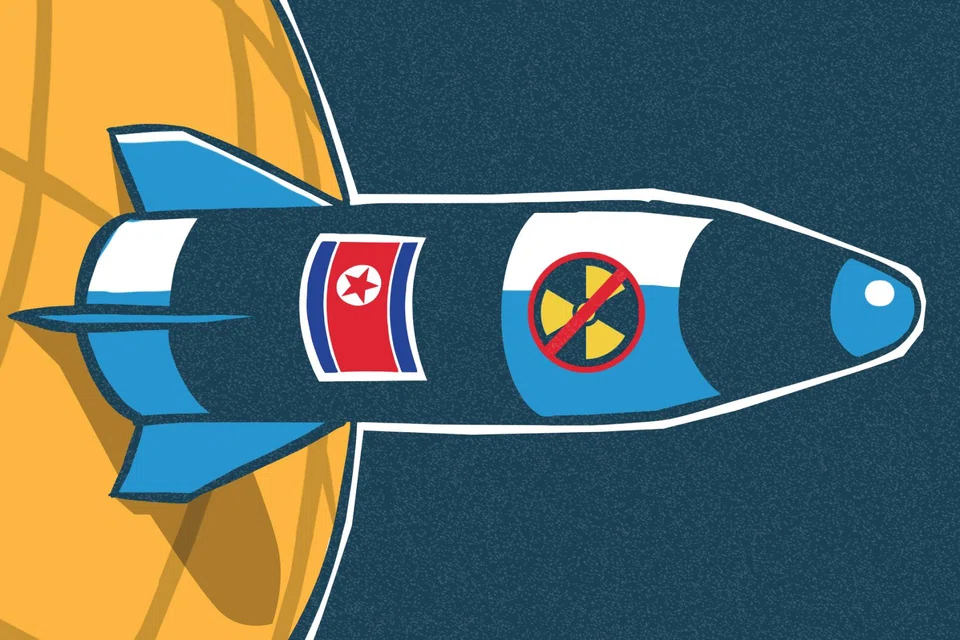

Since withdrawing from the nuclear non-proliferation treaty in 2003, Pyongyang has reportedly amassed about 50 warheads and tested several intercontinental ballistic missile designs. ILLUSTRATION: THE STRAITS TIMES

Will they, or won’t they?

Speculation is rife that Mr Trump and Mr Kim Jong Un could hold another summit in 2026 after Washington and Beijing quietly excised North Korea and another reference to denuclearisation from their flagship security documents within the span of a week in November.

With immediate denuclearisation seemingly no longer a point of contention, parties could be creating space to resume talks with the North that have been stalled for years.

Released in late November, China’s latest White Paper on arms control dispensed with its “denuclearisation” goal for Pyongyang – a significant shift – while the Trump administration dropped all references to North Korea for the first time in its National Security Strategy, which was released in early December.

Seoul, too, has adjusted its rhetoric. Speaking at the UN General Assembly in September, South Korean President Lee Jae Myung conceded that denuclearisation is not a short-term prospect and instead called for a “pragmatic and phased” approach that prioritises drawing Pyongyang back to the negotiating table.

Short of recognising North Korea as a nuclear state, these moves signal a tacit acceptance that Pyongyang’s nuclear capability is a reality that needs to be managed.

Since withdrawing from the nuclear non-proliferation treaty in 2003, Pyongyang has reportedly amassed about 50 warheads and tested several intercontinental ballistic missile designs that could hit the continental US.

For Washington, dropping references to denuclearisation presents a middle ground that could hopefully bring North Korea back to the negotiating table and curb the rise of the “axis of upheaval”, which refers to the anti-Western coalition of China, Russia, North Korea and Iran.

A third Trump-Kim meeting dangles the prospect of US sanctions relief for North Korea’s struggling economy, but it comes at high risk of a second public humiliation if talks should fail again. Memories linger of when Mr Trump unceremoniously walked out on Mr Kim’s demands in Hanoi in 2019. That was their second meeting, with the first held in Singapore in 2018.

Still, Washington retains strategic utility for Pyongyang. As Honolulu-based think tank East-West Center’s senior fellow Denny Roy argues, North Korea has long sought to diversify its dependence on great powers.

Adding Washington to its ties with Moscow and Beijing, he told ST, would give Mr Kim even greater strategic room for manoeuvre. – Wendy Teo

Is terrorism making a big comeback?

A quarter of a century after Al-Qaeda hijackers turned planes flying over the US into weapons, terrorism continues to cast a long shadow over South-east Asia.

What once was a threat fomented by large networks and disciplined cells has mutated into something looser and harder to trace. Terrorism now spreads through digital subcultures, imported grievances from global conflicts and in dark corners online.

Online gaming has turned into one of the most striking developments in the evolution of radicalisation, in which platforms like PUBG: Battlegrounds and Roblox are exploited for harmful purposes. Recruiters have moved from social media feeds into these immersive game worlds where young people spend much of their time, using private servers and team chats to seed harmful ideas.

Recent incidents in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia show that these virtual spaces are no longer fringe concerns but active fronts in South-east Asia’s security landscape.

Another worrying frontier is the adoption of artificial intelligence, or AI, in extremist content, which will continue to increase. ISIS-linked networks are already using generative tools to craft persuasive sermons, doctored images and recruitment materials that can be broadcast worldwide at almost no cost. Circulated through encrypted WhatsApp and Telegram micro-groups, these posts often disappear within hours, leaving hardly any forensic evidence behind.

Unlike in 2001, terrorism in 2026 is no longer defined solely by jihadist extremism. Nor is South-east Asia immune to the effects of the global rise of right-wing movements, anti-Semitic narratives and Gaza-related polarisation, all amplified by social-media algorithms that reward outrage and emotional content.

The December 2025 mass shooting at Sydney’s Bondi Beach , which killed 15 people in what the authorities said was an anti-Semitic terrorist attack, has renewed concerns about lone-wolf violence inspired by global ideologies.

The challenges ahead expose the limits of South-east Asia’s counter-terror model, which has been built on community vigilance, religious engagement and family interventions. Such tools are built for threats anchored in physical relationships, but teens now drifting into extremist content often have no meaningful offline networks tied to their online behaviour.

Many are motivated by alienation or identity struggles, making them far harder to detect and rehabilitate.

The challenge for 2026 is whether South-east Asian nations are able to modernise their security architecture quickly enough. This includes gearing digital forensics towards gaming platforms, cross-platform data-sharing, interventions for pre-teens and new frameworks to deal not only with radical Islamist content, but also with online right-wing and anti-Semitic narratives. – Hariz Baharudin

Is AI due for a reality check?

The year 2025 was when advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) might have broken the metaphorical speed limit, fuelled by great power competition, billions of dollars in investments and breakthroughs that boggled the human mind.

The big question as the world heads into 2026 is whether this momentum can be sustained or if the massive financial and environmental costs, ethical concerns and market saturation of AI technology will force a speed breaker.

When an AI bot was prompted with this question, it was quick to reply. The key phrase, it said, would be “pragmatic specialisation”.

Without further prompting, it elaborated: “The era of simply scaling up model size – the brute-force approach that drives both excessive hype and high environmental cost – is maturing. Instead, the focus will be on me, the AI, becoming context-aware, locally optimised and resource-efficient.”

In simpler “human” language, instead of bigger, costly and possibly wasteful models, further advancements are likely to be making AI cheaper, locally relevant and more energy-efficient.

While this response might be disappointing to some who were hoping to see greater strides in 2026, it provides perhaps a much-needed reality check.

The gap between reality and hype regarding advancements in AI and what it can actually do might have grown. While there have been massive strides in AI technology – particularly in real-world applications for healthcare, education and defence – the full extent of their results and continued potential have yet to be properly understood.

Further expansion of AI in Asia is likely to face constraints beyond technical feasibility.

The AI drive has given rise to serious environmental and other types of non-traditional security concerns, in particular, limits of local infrastructure and the trade-offs affecting general living conditions.

Johor’s rise as a regional AI data centre hub raised questions over water security, leading the state to stop approving licences for Tier 1 and 2 data centres, which require more water for their operations.

With local communities starting to push back against the rapid construction of data centres in the US, will the same happen in Asia? Or will history prove the AI evangelists right? – Kalicharan Veera Singam

Will India and China be equal partners?

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s first visit to China in seven years in August – to attend a summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation – marked the culmination of a months-long detente between two of Asia’s largest economies.

Nonetheless, New Delhi remains leery of Beijing’s dominance.

While both countries have cast themselves as leaders of the developing world, China appears to be broadening its global ambitions and championing a new-found sense of inclusiveness through two initiatives announced in 2025.

First, its Global Governance Initiative proposes to reform West-centric international systems in favour of greater equity and representation for developing countries. Second, the Communist Party in April held a high-level Central Conference on Peripheral Work meeting to strategise China’s engagement with its neighbours and address other broader global challenges.

With China an influential founding BRICS member, the China-India “rivalry” could well come into sharp focus when India takes over as the grouping’s chair in 2026. Mr Modi has vowed to give a “new form” to Brics during India’s tenure.

“The dominance of China poses some tricky challenges for India,” said Professor Harsh V. Pant, a vice-president at New Delhi-based think-tank Observer Research Foundation.

“The fact that China is dominant and that increasingly it’s willing to use platforms like BRICS to serve its national interest is something India will have to take into account.”

Founded in 2009 with Brazil, Russia, India and China as the original members, the BRICS grouping has since pitched itself as a counter to the West in the Age of Trump 2.0 and now includes South Africa, the United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran and Egypt as members and more than a dozen partner countries, including Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand.

With its economic heft, China’s dominance has grown not just in this multilateral grouping with divergent interests, but also globally.

This was acutely evident in protracted trade negotiations with the Trump administration, where Beijing showed that it is more than Washington’s equal. India, by contrast, is still seeking a trade pact, faced with punitive 50 per cent tariffs on its US exports for its purchases of Russian oil and gas, even though China is also a major buyer.

What’s more, Mr Trump has become friendly with Pakistan, India’s arch-nemesis , thus turning his back on his predecessors’ efforts in cultivating ties with New Delhi as a strategic counter to China. India-US relations are now in the troughs last seen when India declined to sign the nuclear non-proliferation treaty in the 1990s, and when it chose non-alignment in the 1960s, seeking a middle path between the Soviet Union and the US.

India is once again looking to thread the needle, attempting to maintain strategic autonomy and stay above the fray where great rivalries and attritional conflicts are playing out.

India’s perception of its place in the world is likely to be tested more severely by fast-evolving realities in 2026. What may seem like strategic non-alignment to New Delhi could turn out to be an act of casting itself adrift at sea in this historic moment. – Nirmala Ganapathy

Arlina Arshad is The Straits Times’ Indonesia bureau chief. She is a Singaporean who has been living and working in Indonesia as a journalist for more than 15 years.

Bhagyashree Garekar is The Straits Times’ US bureau chief. Her previous key roles were as the newspaper’s foreign editor (2020-2023) and as its US correspondent during the Bush and Obama administrations.

Clement Tan is an assistant foreign editor at The Straits Times. He helps to oversee coverage of South Asia, the US, Europe, the Middle East and Oceania.

Hariz Baharudin is a correspondent at The Straits Times covering South-east Asia.

Kalicharan Veera Singam is Assistant Foreign Editor at The Straits Times.

Mara Cepeda is Philippines correspondent at The Straits Times.

Nirmala Ganapathy is India bureau chief at The Straits Times. She is based in New Delhi and writes about India’s foreign policy and politics.

Walter Sim is Japan correspondent at The Straits Times. Based in Tokyo, he writes about political, economic and socio-cultural issues.

Wendy Teo is The Straits Times’ South Korea correspondent, based in Seoul. She covers issues concerning the two Koreas.

Yew Lun Tian is a senior foreign correspondent who covers China for The Straits Times.