October 7, 2022

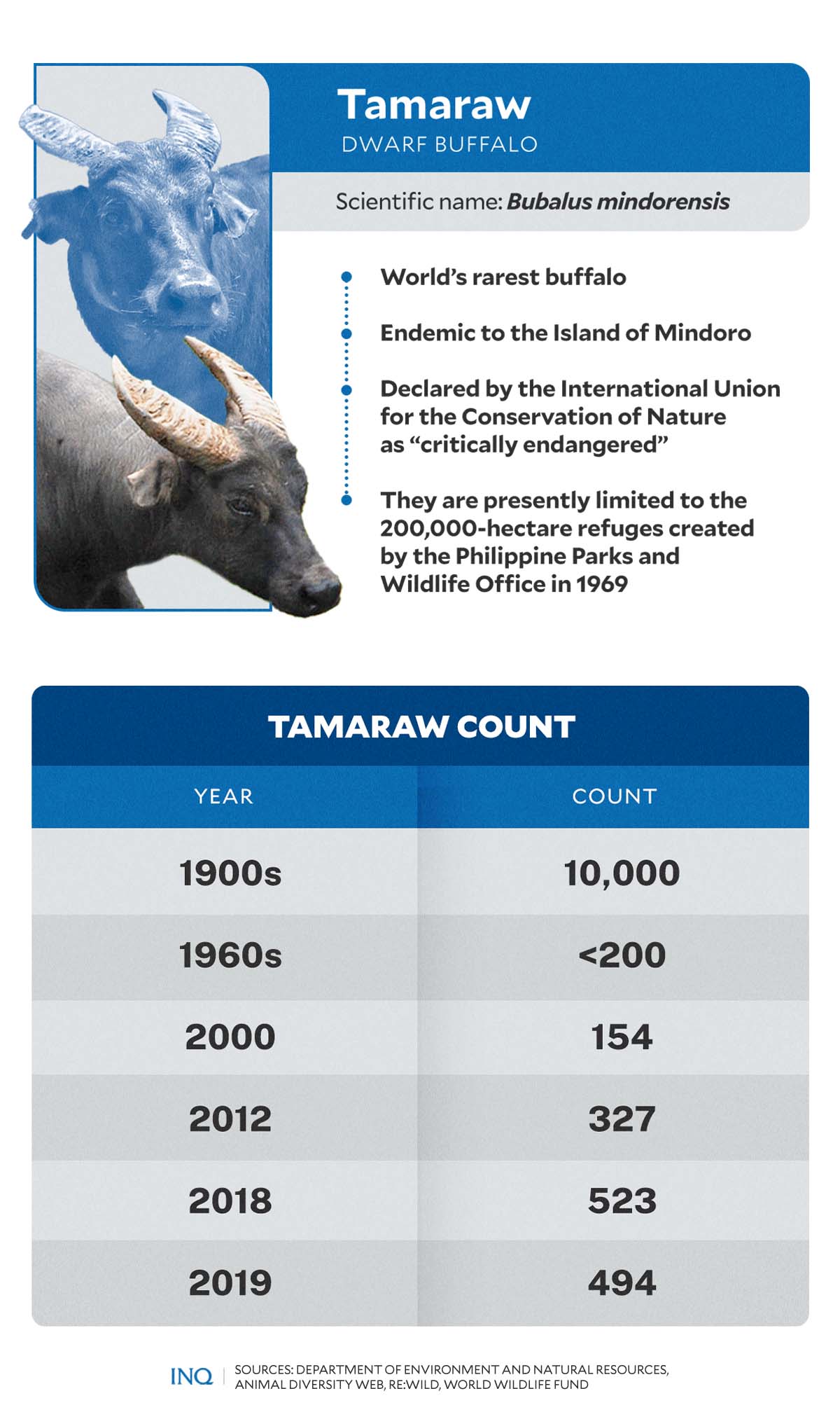

MANILA – There were 10,000 tamaraw that once lived on the island of Mindoro, but as the years passed, the population of the world’s rarest buffalo, which is endemic to the Philippines, fell to 154 in the year 2000.

According to data from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR)-Mimaropa, the tamaraw population fell over the decades, stressing that as early as the 1960s, the count already dwindled to less than 200.

As a result, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed the tamaraw as critically endangered, indicating that serious efforts were needed to save the tamaraw from extinction.

This was the reason that in 2002, then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo signed Proclamation No. 273 that declared October of every year as a “Special Month for the Conservation and Protection of the Tamaraw in Mindoro.”

The proclamation said there was a need to instill into the minds of Filipinos the significance of the tamaraw as a natural heritage and as a biological resource that offers “ecological, economic, educational, historical, and scientific values.”

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The proclamation encouraged all government offices and officials on the island of Mindoro to implement activities geared toward the conservation of the tamaraw and its habitat.

This, as the tamaraw, which is the largest mammal found in the Philippines, is found only in the island of Mindoro and currently calls home the 200,000-hectare refuge created by the Philippine Parks and Wildlife Office in 1969.

Dwindling population

According to data from the asianwildcattle.org, Asia has wild cattle species, including the tamaraw, but all are now threatened with extinction, with some already declared as critically endangered.

How did this happen?

June Pineda, coordinator of the Tamaraw Conservation Program (TCP) of the DENR, had said the decline in tamaraw population could be attributed to “continued habitat destruction, hunting, and poaching.”

As stressed by globalforestwatch.org, Oriental Mindoro had 148,000 hectares of natural forest, extending over 69 percent of its land area, but as years passed, it lost 580 hectares of natural forest.

Oriental Mindoro, from 2002 to 2021, had lost 511 ha of primary forest, making up 2.3 percent of its total tree cover loss, globalforestwatch.org said, pointing out that in only 20 years, the province’s primary forest area decreased by 1.7 percent.

The website speciesonthebrink.org said the main threat to the tamaraw in the 20th century was habitat degradation because of farming by resettled people and locals, with high resident population growth within and near the remaining tamaraw habitats.

It stressed that in some areas, fires set for agriculture threatened the species’ home, while cattle ranching posed risks, including the spread of diseases to the dwarf buffalos from livestock.

Tamaraw, the speciesonthebrink.org said, were hunted for both subsistence and sport, which led to a drastic decline in their population: “Although protected by law, the illegal capture and killing of this species continues.”

It was on Oct. 23, 1936 when Commonwealth Act No. 73 was signed to prohibit the killing, hunting, wounding or taking of Bubalus mindorensis, which is commonly known as the tamaraw.

We’re failing them

As stressed by asianwildcattle.org, which is engaged in the conservation of buffalos, three of the wild cattle species in Asia, including the tamaraw, had been declared by the IUCN as critically endangered.

- Anoa (Bubalus depressicornis & Bubalus quarlesi) of Indonesia is endangered

- Banteng (Bos javanicus) of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam is endangered

- Gaur (Bos gaurus) of Thailand, India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and China is vulnerable

- Kouprey (Bos sauveli) of Cambodia is critically endangered, possibly extinct

- Saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) of Laos and Vietnam is critically endangered

- Wild Water Buffalo (Bubalos arnee) of Southeast Asia is endangered

- Wild Yak (Bos mutus) of China and India is endangered

Like the tamaraw, the remaining species of wild cattle in the continent are threatened by habitat degradation, hunting, spread of diseases, and even interbreeding with domestic cattle, said the website.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The website rewild.org said tamaraw “may feign toughness, but they need our help to make a full comeback,” especially since threats have sent their population spiraling downward over the years.

Bringing them back

The DENR revealed that from 154 in the year 2000, the population of the tamaraw grew to 327 in 2012 and 523 in 2018, but the count again dwindled to 466 to 494 back in 2019.

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) had said there have been new populations confirmed outside of Mounts Iglit-Baco Natural Park, which is the area known to have the highest concentration of the world’s rarest buffalo.

There were 1,480 tamaraw confirmed in Mounts Iglit-Baco, while new populations were confirmed by the DENR-TCP using new survey methodologies.

A population of tamaraw was identified in the Upper Amanay Ranges on the border of Occidental and Oriental Mindoro, while another is believed to inhabit the Aruyan-Malate Critical Habitat in Sablayan, Occidental Mindoro.

This suggests an increase in the tamaraw population throughout all of Mindoro. Calves and newborns were identified among the population, proving that the species has indeed continued to breed and grow in numbers.

“Beyond Mts. Iglit-Baco, the DENR-TCP works with organizations such as the Mindoro Biodiversity Conservation Foundation Inc. to conserve local ecosystems and species, including the tamaraw,” it said.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Based on a 2018 article by the Global Wildlife Foundation, some of the tamaraw populations either vanished or were reduced to such low numbers that they will likely disappear soon without human intervention.

Today 80 percent of all tamaraw live in Mounts Iglit-Baco Natural Park.

It said the National Tamaraw Conservation Action Plan now lays out a bold vision to continue the upward population trend beyond even Mounts Iglit-Baco Natural Park.

“By the year 2050, the tamaraw, a source of national pride and a flagship for Mindoro’s natural and cultural heritage, thrives in well-managed habitats and populations that co-exist with indigenous people across Mindoro.”

“There’ve been anecdotal reports of sightings in certain areas, but those couldn’t be validated. Only in 2019 was there validation. There’d been sightings of manure and markings before, but this is the first time anyone’s actually seen and counted these populations,” said WWF-Philippines Western Mindoro Project Manager Luis Caraan.

Before 2019, confirmed tamaraw sightings had been limited to Mounts Iglit-Baco Natural Park. In 2018, all 523 tamaraw were counted in the natural park during the 2018 Tamaraw Population Census by the DENR-TCP, WWF-Philippines and partner organizations.

“This is good news, and it shows that the tamaraw exist all over Mindoro. The presence of calves is also proof that the population is increasing. What we need to think about is, why were they confined to these areas?” he said.

Caraan had explained how human activity had drastically reduced the tamaraw population from its historic numbers.

This has driven the endemic buffalo to sparse corners of Mindoro island, with small and unconfirmed pockets of individuals outside Mounts Iglit-Baco Natural Park, said Caraan.