August 25, 2023

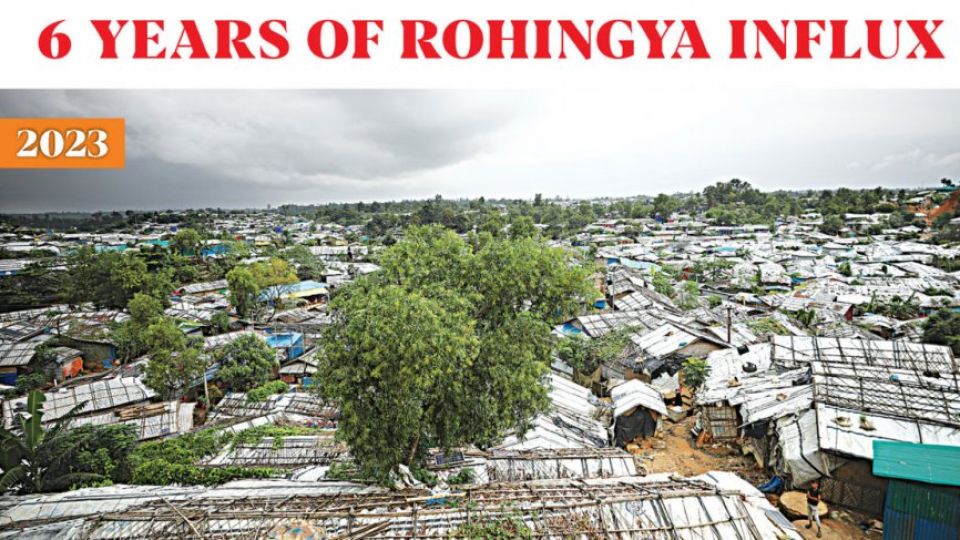

DHAKA – Six years into one of the world’s biggest refugee crises, the fate of more than one million Rohingyas sheltered in Cox’s Bazar hangs in the balance as efforts to repatriate them see little progress due to increased global geopolitical tension.

Geopolitical analysts and diplomats say while Myanmar continues to deny citizenship and ethnicity to the Rohingyas, polarisation between the global powers has intensified on account of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, casting doubt on the possible solution to the crisis.

“China has recently ratcheted up its engagement with Myanmar for Rohingya repatriation. However, the US does not want the repatriation under Chinese leadership, especially when the Myanmar military is in power, oppressing pro-democracy civilians,” a foreign diplomat based in Dhaka said requesting anonymity.

Washington, which gives the most amount of money to deal with the crisis, does not support the Beijing-led repatriation efforts as it will not be sustainable under the current political and security conditions in Rakhine, the diplomat said.

The UN also thinks that the conditions in Rakhine are not conducive to repatriation.

Since the beginning of the Rohingya crisis in 2017, there has been geopolitical tension with the UN Security Council divided over the issue. The situation has worsened following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in which the US and its allies have taken a strong position against Russia and its allies, including China.

Meanwhile, as of mid-August, funding for the Joint Response Plan for the Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis totalled less than a third of its $876 million overall appeal, according to a statement issued by the UN refugee agency, UNHCR.

Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen said the Rohingya crisis appears to become a “geopolitical game”.

“Our only demand is the repatriation of the Rohingyas to their homes, not to stay in the camps,” he recently told The Daily Star.

Commenting on the issue, Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner Mohammad Mizanur Rahman, “We have allowed the Rohingyas to stay on our land, we’re working round the clock to manage them, which is very costly. Now, if the international community cuts the funding for them and expects that we channel a portion of our development fund for them, it is too much for us.”

HOW IT GOT COMPLICATED

Bangladesh and Myanmar signed a repatriation deal on November 23, 2017, three months after around 750,000 Rohingyas fled a brutal military campaign in Myanmar’s Rakhine State and entered Bangladesh, joining 300,000 others who had fled earlier waves of violence since the 1970s.

Dhaka and Naypyidaw have since held series of meetings. In 2018, China, which opposed internationalising the issue, took a trilateral initiative. Two repatriation attempts, one in 2018 and the other in 2019, fell flat as Myanmar met none of the demands made by the Rohingya — guarantee of safety, citizenship, and ethnicity recognition.

After a two-year gap caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, Dhaka and Naypyidaw met in January last year.

Earlier this year, China became very active, with Chinese Special Envoy for Asian Affairs Deng Xijun visited Dhaka twice — first in April and then again on August 1 this year. Bangladesh’s Foreign Secretary Masud Bin Momen also visited China and met the Chinese and Myanmar officials in Kunming on April 18.

In May this year, a 17-member Myanmar delegation visited the Rohingya camps in Cox’s Bazar while a group of Rohingyas for the first time visited Rakhine to see the reality on the ground.

During his latest meeting in Dhaka, Deng Xijun, who met the Myanmar authorities several times in recent months, informed foreign ministry officials that Myanmar agreed to settle the Rohingyas in their original villages — a demand that the Rohingyas have been making in response to Myanmar’s earlier plan of resettling them in camps or model villages.

China genuinely wants the Rohingya repatriation as part of its greater goal of regional stability and development, a Chinese diplomat in Dhaka told this correspondent, wishing not to be named.

When asked about the citizenship and ethnicity recognition of the Rohingyas, he said it was up to the Myanmar government to decide.

Rohingya activist Nay San Lwin, coordinator of the Germany-based Free Rohingya Coalition, expressed his suspicion about the Myanmar junta’s efforts for repatriation.

The military, which brutally killed the Rohingyas and burnt them and their villages, is now in power, he said.

“I don’t think repatriation will happen as long as the military is in power,” he told The Daily Star on August 23.

What the military wants to do is to tackle the pressure coming from the western countries and the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which ordered Myanmar to refrain from committing any genocidal acts against the Rohingyas.

“If the Myanmar junta was really sincere, it would amend the citizenship law and recognise our ethnic identity. That has not happened, however. This is enough to describe the character of the junta,” Nay San Lwin said.

The Gambia filed the genocide case with the ICJ in 2019.

North South University Prof SK Tawfique M Haque, who researches the Rohingya crisis, said China wants to build its image as a global peace negotiator by leading the Rohingya repatriation, after it brokered a peace deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran in March this year.

When it comes to ensuring the Rohingyas’ legitimate right to citizenship, Myanmar does not comply as it should, he said.

“Myanmar’s apparent willingness to accept the Rohingyas in limited numbers can be considered as a deception to improve its reputation at the ICJ,” said Prof Tawfique, director at NSU’s South Asian Institute of Policy and Governance.

On the other hand, the US, which declared the atrocities against the Rohingyas as acts of genocide, supports the ICJ case and unequivocally opposes the Myanmar junta, which took power by ousting Aung San Suu Kyi’s civilian government in 2021.

The US’s amended BURMA Act late last year has broadened the Biden Administration’s authority to impose sanctions against Myanmar and aid opposition parties and groups resisting the junta. The act also talks about repatriation and protection of the Rohingyas and other ethnic minorities by eliminating structural barriers, he said.

“The US is likely to take serious measures against the junta next year,” the professor said, noting the Biden administration’s prioritises democracy and human rights.

Apart from being a signatory to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Myanmar is also geopolitically important because it provides China access to Southeast Asia and the India Ocean region, Prof Tawfique said.

Foreign policy analysts said major global powers’ focus is on the Indo-Pacific. The US and its allies are active in reducing Chinese influence here and will continue to work to that end.

Russia, which is facing huge pressure mainly from the US-led Western allies, is meanwhile a major arms supplier to the Myanmar junta. Though Bangladesh and Russia have a strong relation, Russia, like China, vetoed on a resolution on the Rohingyas at the UN Security Council.

Jahangirnagar University’s Department of Government and Politics Prof Tarikul Islam said China and India, motivated by their geopolitical and economic stakes in Myanmar, sided with the junta on the Rohingya issue.

Myanmar’s strategic value to China includes access to the Indian Ocean. Further, China’s construction of the Kyauk Phyu port in Myanmar aims to diversify supply routes and reduce dependence on the Middle East, he pointed out.

On the other hand, Myanmar provides a port for Russian ships travelling to the Indian Ocean. Thus, Russia seeks to establish a visible presence in the Indian Ocean, Prof Tarikul said.

Wishing anonymity, a foreign diplomat said Bangladesh should have approached the UN for coordinating the whole repatriation issue, instead of taking a bilateral path.

“Even now, it is not impossible. Dhaka should engage all the major global stakeholders including the UN, the US, China, and India in the repatriation effort.”