November 1, 2023

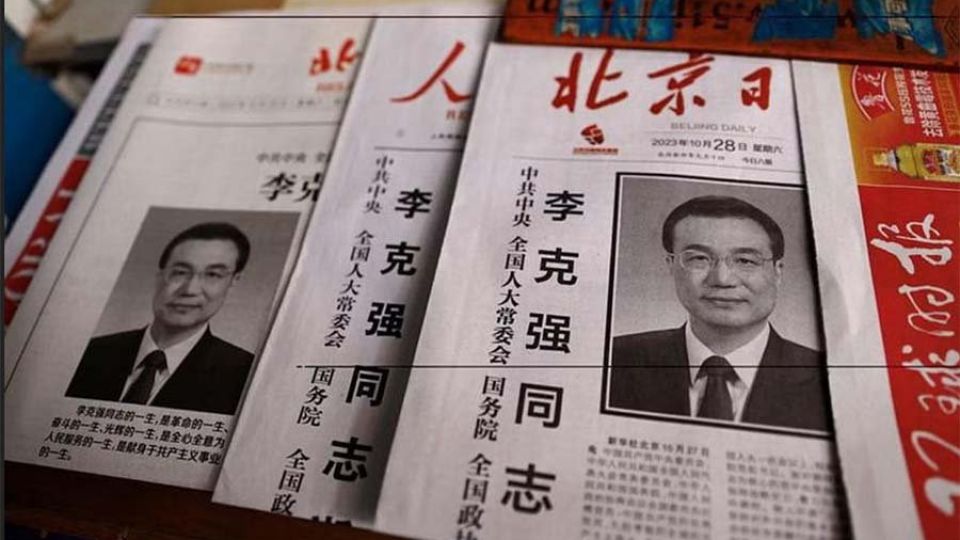

BEIJING – In parks and public squares from Shenzhen to Chengdu, bouquets, cards and banners have been laid out in tribute to former Chinese premier Li Keqiang, who died of a heart attack on Friday, aged 68.

Outside his childhood home in Hefei in central Anhui province, bouquets of yellow and white chrysanthemums, used in mourning in Chinese culture, quickly piled up to cover almost the entire side of his former home by Saturday, then spilling over to an adjacent road by Tuesday.

Such is the outpouring of grief for Mr Li, who was the first Chinese premier armed with a doctorate in economics but was largely sidelined by Chinese President Xi Jinping.

On Tuesday, Beijing announced that Mr Li will be cremated in a ceremony on Thursday, which will be declared a national day of mourning with flags flying at half-mast at Tiananmen Square and all government buildings.

The arrangements for Mr Li’s funeral will follow those for former premier Li Peng in 2019, which means there will probably be a ceremony at the Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery, west of Beijing, where members of the Politburo Standing Committee and important political figures will pay their final respects.

While allowing for some public expressions of sadness over Mr Li’s death, Beijing is taking steps to prevent the mourning from developing into criticism of the current administration.

Outside Mr Li’s childhood home, guards and volunteers in blue vests are keeping watch, according to social media posts. They inspect the cards offered with the floral tributes, looking out for messages that might be seen as subversive.

In cities like Wuhan and Qingdao, the local authorities were seen to have begun clearing out flowers and posters left by mourners and finding ways to prevent mass gatherings.

In Wuhu, a city in Anhui province, municipal workers apparently cleared a lakeside tribute overnight, leaving nary a trace of the dozens of bouquets, candles and posters that had been placed the night before, social media pictures showed.

At the popular People’s Park in Chengdu, social media posts showed that officials have erected barricades around the Railway Protection Movement Monument, a martyrs’ memorial and a focal point for the tributes.

The Chinese state media has been silent on the unofficial memorial activities, and censors have been carefully scrubbing anything that could be construed as a criticism of the current government.

On Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, a group of users were warned by local police after they made arrangements to gather on Sunday night for a vigil for Mr Li.

In a country where the Internet is tightly monitored for any sign of dissent, the deaths of public figures are often used as a pretext to express unhappiness over a variety of issues.

In 2020, after the death of Dr Li Wenliang, who had warned about a new pneumonia-like virus in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, his Weibo page turned into a “wailing wall” of sorts for many to project their emotions.

In particular, the mourning of a political leader is tricky business for the Communist Party of China because such events have previously ignited anti-party sentiments that later grew into large-scale protests.

Most notably, in April 1989, university students flocked to Tiananmen Square to mourn the death of former leader Hu Yaobang. This grew to become pro-democracy protests that were crushed by the military on June 4 that year.

Mr Li was nowhere as popular as Mr Hu, who had engaged in sweeping liberal reforms, but there are posts online praising him as a “moderate”, said Dr Olivia Cheung, a research fellow at the SOAS China Institute in London.

Some of these posts have been censored because praise for Mr Li can also be seen as criticism of Mr Xi, under whose shadow he governed over the past decade.

“(The leadership) needs to provide scope for the public to show respect to Li Keqiang, not least because there’s genuine respect for him in Chinese society and the Chinese Communist Party, but there’s no scope for them to show respect, to the extent that it would backfire on Xi’s own legitimacy,” she told The Straits Times.

“Li Keqiang, alive or dead, must not be allowed to be used to undermine Xi.”

Professor Lynette Ong who specialises in political science at the University of Toronto, said Mr Li’s relative openness and reformist outlook, especially in comparison with Mr Xi, has made the former premier’s legacy seem “outstanding” to many Chinese.

Mr Li, for example, had promoted what he himself described as “mass entrepreneurship and innovation”. In 2015, he introduced his “Internet Plus” policy, aimed at driving economic growth through integrating the Internet, cloud networking and big data with traditional industries to foster new businesses.

In China, some people also saw themselves in Mr Li, who had found himself shunted aside by his erstwhile political rival, Mr Xi. Like Mr Li, they were people who had “struggled over the past decade but have gradually lost out”, said a widely circulated social post that has since been censored.

Referring to the public mourning for Mr Li, Prof Ong said: “This is an event that Xi wants to handle with care.”