February 22, 2024

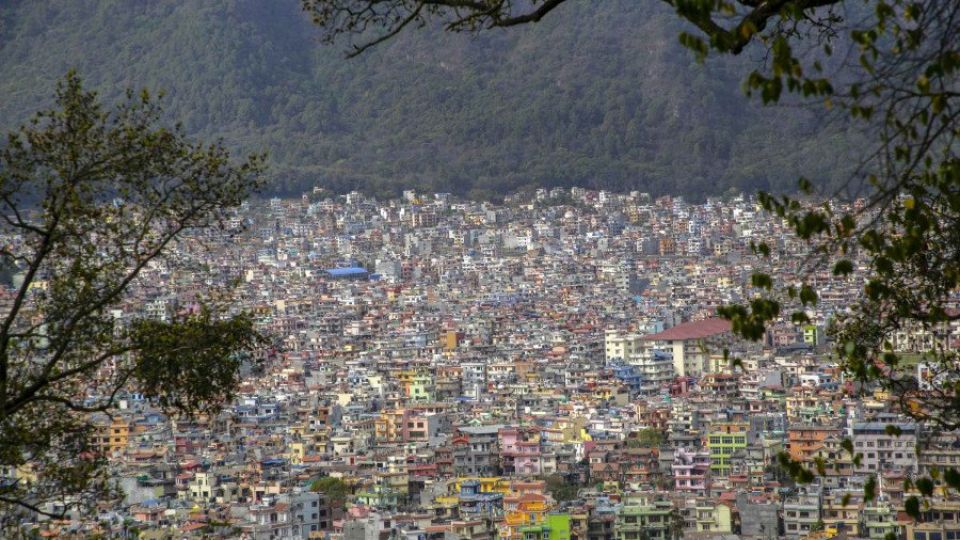

KATHMANDU – Nepal’s rural poverty has been in constant decline while urban poverty has been on the rise as people continue to migrate to urban centres to improve their livelihood.

The fourth Living Standard Survey 2022-23 released recently by the National Statistics Office revealed that urban poverty in the country rose to 18.34 percent in 2022-23 from 15.46 percent in 2010-11.

On the other hand, rural poverty decreased from 27.43 percent in 2010-11 to 24.66 percent in 2022-23.

Before that, urban poverty had declined to 9.55 percent in 2003-04 from 21.55 percent in 1995-96, the first time the Living Standard Survey was carried out in the country. The proportion of urban poor has increased substantially in consecutive surveys.

Meanwhile, rural poverty, which stood at 43.27 percent in 1995-96, has declined consistently.

“The portion of urban poor in the latest living standard survey was established based on those who live below the poverty line in the municipalities,” said Hem Raj Regmi, deputy chief statistician at the National Statistics Office.

According to the latest census of 2021, as much as 66 percent of the country’s population live in the municipalities. There are 293 municipalities in the country across 753 local units.

“It means the number of poor people in municipalities should be higher than those living in the rural municipalities even though the rural municipalities have a higher poverty ratio,” Regmi said. “People are migrating to urban areas seeking better educational, health and job opportunities, leading to a rise in urban population.”

For example, the latest census showed that the population in Kathmandu Valley and Pokhara collectively increased by 1.1 percent from 2011 to 2021.

A rapid change in demographics is a major contributor to the creation of the urban poor who live in major cities of Nepal with minimum facilities.

Urbanisation is a global phenomenon and the proportion of urban population living in the slums worldwide is on the rise.

According to the United Nations Statistics Division, between 2014 and 2018, the proportion of the urban population living in slums worldwide increased from 23 percent to 24 percent, translating to over 1 billion slum dwellers.

Slum dwellers are most prevalent in three regions: Eastern and South-Eastern Asia (370 million), sub-Saharan Africa (238 million) and Central and Southern Asia (226 million), according to the UN body.

They live without access to adequate shelter, clean water, and basic sanitation. Overcrowding and environmental degradation make the urban poor particularly vulnerable to the spread of diseases.

When Kathmandu Metropolitan City sought to drive away slum dwellers in 2022, the Human Rights Watch, the international non-governmental organisation, had condemned the metropolitan city’s act.

“The policies of the Kathmandu Metropolitan City administration towards street vendors, landless people, and begging are threatening the human rights of thousands of city residents,” Human Rights Watch had said. “They include the rights to work, to housing, and to an adequate standard of living.”

Nepal’s Urban Development Strategy 2017 has talked about developing a productive and vibrant urban economy with a quality of growth that creates wealth and employment opportunities, and providing jobs for the urban poor.

It discusses design capacity building training and orientation programmes for informal sector workers. Likewise, it talks about identifying socio-economic and spatial characteristics of urban poor—through poverty profile and/or poverty mapping.

To alleviate poverty, the strategy further suggests implementing targeted Community Development Programme (CDP) focused on urban poor that would follow group discussions and pro-poor urban planning (housing, infrastructure, transportation).

But the relevant ministry of the central government has hardly been implementing specific measures to address the issues of urban poor.

Ganesh Prasad Bhatta, spokesperson at the Ministry of Land Management, Cooperative and Poverty Alleviation, admitted that his ministry has hardly run programmes on poverty alleviation, including urban poverty.

“Other ministries, provincial and local governments have their own programmes to address the issues of poverty,” he said. “Our ministry does not have any specific programme related to poverty alleviation.”

The Poverty Alleviation Ministry is, however, implementing the programme ‘Bishweshwar with the Poor’, a poverty reduction scheme being run for a long time under the name of the late prime minister Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala. The ministry supports local governments to implement this programme but this is not urban poor-specific, according to Bhatta.

Earlier, the government had decided to shut down the Poverty Alleviation Fund, an agency formed to run targeted programmes during the conflict period, after donor funding dried up.

Currently, the Ministry of Land Management, Cooperatives and Poverty Alleviation has been collecting data on poor households and their certification.

“We have already finalised the data about poor households of 49 districts and around 800,000 families have been confirmed as poor in these districts,” said Bhatta. “Data processing is in the final phase in 15 districts and data collection has been completed in the other 13 districts.”

He said targeted poverty alleviation programme could be launched based on these data.

Experts say creating more jobs in urban areas including by promoting self-employment was necessary to alleviate urban poverty.

“Creating jobs outside the agriculture sector, employing the urban poor in various industries and boosting their skills to enable them to earn more can be measures to address the issues of urban poor,” Regmi said.