July 12, 2024

ISLAMABAD – Imagine a world with just five billion people. It was on July 11, 1987, when this milestone was reached, marking the first World Population Day (WPD). Fast forward to 2023, and our planet now teems with a staggering eight billion inhabitants. This explosive growth shines a light on the pressing challenges and opportunities that come with such a rapidly expanding global population, impacting sustainable development, health, and well-being.

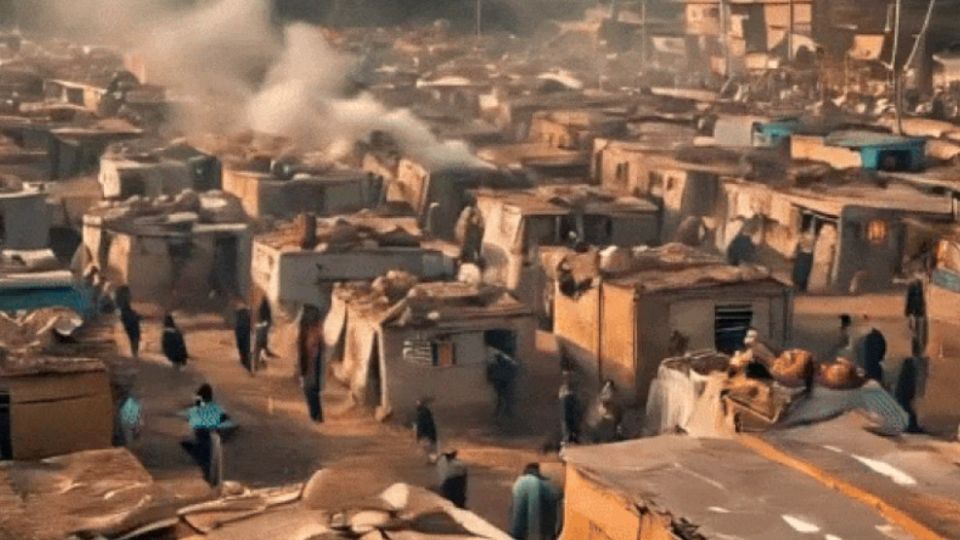

In the heart of this demographic surge lies South Asia, home to over 2.2 billion people. Among these nations, India leads with a population of 1.4 billion, followed by Pakistan’s 240 million, and Bangladesh’s 172 million. These figures are not just numbers; they are the pulse of a region undergoing significant demographic shifts, demanding urgent and effective policies to manage these changes.

Pakistan, in particular, faces a daunting scenario. With the highest population growth rate in South Asia at 1.96 per cent, the country grapples with a myriad of challenges. The quality of human resources is under strain, resources are stretched thin to meet the growing demands, and the nation remains vulnerable to extremism and climate change shocks.

Fertility rates — a tale of uneven strides

From 2010 to 2015, Pakistan’s fertility rate stood 69pc higher than that of Turkey, Iran, India, Indonesia, and Bangladesh. Today, its fertility rate of 3.6 remains the highest in South Asia, painting a rather bleak picture of its demographic reality.

It is, therefore, imperative to scrutinise policies that have failed to curb skyrocketing population growth.

Pakistan kicked off its family planning initiative in 1965, while Bangladesh followed suit a decade later in 1975. Today, the reproductive health metrics of these two nations tell a different story. Bangladesh’s family planning programme has been nothing short of a miracle, catapulting the contraceptive prevalence rate from a meagre 8pc in 1975 to an astounding 62pc in 2018. Alongside this surge, the total fertility rate dropped from 6.3 to just 2.3 children per woman.

Pakistan’s progress, though commendable, is a tale of uneven strides. The reduction in fertility rates and population growth has predominantly benefited the affluent. The Pakistan Demographic Health Survey reveals that in the lowest wealth quintile, the total fertility rate was a daunting 5.8 in 2006-07, slightly dipping to 4.9 in 2017-18. On the flip side, the upper quintile saw rates of 2.3 and 2.8, respectively, during the same periods.

This stark disparity demands a deeper dive into the root causes and the intricate decision-making processes at play. High fertility rates remain entrenched among the poorer segments of society, who view children as essential contributors to family income. Understanding and addressing these complex dynamics is crucial for crafting effective population control policies.

Young, uneducated and overlooked

In 2016-17, 13.7pc of children aged 10-17 were trapped in child labour, as reported by the International Labour Organisation. What’s more alarming is that 5.4pc of these children were engaged in hazardous work which endangered their lives and futures. This exploitation isn’t just a tragedy for the children — it’s a ticking time bomb for the country’s workforce — setting the stage for a generation of illiterate and unskilled laborers.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) sheds light on an even darker reality; 22.8 million children between the ages of five and 16 are out of school in Pakistan. Instead of learning in classrooms, these kids are toiling away in car mechanic shops, selling vegetables on street corners, or begging for their next meal. This dire situation underscores the government’s sheer negligence in harnessing its most valuable resource — its youth.

But there still might be hope. Conditional cash programmes, midday meals, and strict laws against child labour could turn the tide. Policies must focus on adult employment, reducing tax burdens on the poor, providing universal healthcare and education, and expanding social protection coverage for the needy to prioritise the quality over quantity of children.

The focus of family planning policies has been on improving access to contraceptives, which is commendable. However, data reveals that merely expanding outreach is not enough to achieve the desired outcome — significant decline in fertility. Bangladesh’s experience indicates that a multi-pronged approach is necessary.

This involves dismantling gender stereotypes with the help of religious leaders, boosting girls’ school enrolments, and empowering women through self-employment opportunities, digital literacy, and better access to contraceptives throughout the country.

Reproductive rights or wrongs?

In Pakistan, the backlash against family planning advocates isn’t just a debate; it’s a raging misunderstanding. Many, even among the educated, perceive family planning as a violation of their rights to reproduce, depriving them of godsent gifts. This profound misconception has thwarted the success of heavily funded family planning initiatives over the years, underscoring the urgent need to revisit policy strategies.

Traditionally, family planning programmes have targeted women, sidelining men, and family elders. This focus has restricted women’s choices, limiting birth spacing decisions in conventional societies where women often lack a voice in reproductive matters.

Gender stereotypes further ascribe the role of childbearing to women as fundamental to their respectable survival in the family and community. In rural areas, the feudal power structure encourages women to have more children to gain greater agency, as they are entitled to a larger share of land and assets.

Recently, there is a noticeable surge in radical views advocating for restricting women’s mobility, promoting polygamy, and endorsing early-age marriages. If these views do not come into the realm of challenging the law of the country, then what message do they send?

Unfortunately, these extreme elements are freely roaming, enjoying complete freedom to humiliate women publicly, and are being praised by the media and people with vested interests. The government’s role in countering these gender stereotypes is glaringly minimal.

Work or womb — No woman should have to choose

With most lawmakers being male, increasing women’s political participation, especially at the local level, is crucial. This could address pressing issues related to women’s safety, and sexual and reproductive health rights.

The Labour Force Survey data from 1990 to 2020 indicates that female labour force participation plummets around childbearing age. This alarming trend is reflective of the inflexibility of our labour market, plagued by issues such as inadequate maternity leaves, scarce childcare spaces, and insufficient maternal and child healthcare.

On a brighter note, several policies have been introduced to address these constraints head-on. The Maternity and Paternity Leave Act, 2023, Punjab Maternity Benefits (Amendment) Act 2016, Punjab Maternity Benefits (Amendment) Bill 2019, Sindh Maternity Benefits Act, 2018, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Maternity Benefits Act, 2013, all bring crucial reforms.

Yet, their varied provisions and patchy enforcement highlight a pressing need for effective monitoring and accountability mechanisms.

Boosting job quotas for women across all sectors could be a concrete step towards achieving gender equality in the workplace. It’s time to turn policy promises into real-time progress so no woman has to choose between motherhood and her career.

Quality over quantity

Pakistan is grappling with another pressing challenge: the depleting quality of its human resources. The Migration Report 2022 reveals a startling statistic wherein 92pc of Pakistani migrants head to Saudi Arabia and the Middle East. Surprisingly, half of these migrants are either unskilled or low-skilled laborers. Adding to the dismal picture, women constitute a mere 1pc of these outmigrant workers.

But the troubles don’t end there. Desperate for a better life, many working-age Pakistanis resort to illegal channels to migrate. The Federal Investigating Agency (FIA) reports a disgraceful figure — around 250,000 Pakistanis have been deported, predominantly from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. This not only tarnishes the country’s reputation but also points towards a deep-rooted crisis.

The skewed provincial distribution of resources under the National Finance Commission (NFC) is another dilemma we are currently facing. With population accounting for 85pc of the weightage, the formula prioritses numbers over quality.

This reflects a prioritisation that sidelines efforts towards population control, as a larger population means a greater share in national resources and an increased likelihood of forming government at the federal level.

When political success hinges on population size, the quality of the population becomes a secondary concern. There’s a grave need to revise the NFC formula to consider more significant indicators like growing regional disparities and poverty.

The unchecked population growth, coupled with inadequate planning, spells disaster for a country already strained by scarce resources, a rising debt burden, poor growth, and development scenarios. This precarious situation heightens vulnerability to shocks and fuels misogyny.

Gender mainstreaming at all levels of planning and development is of utmost importance to foster an inclusive society. This includes providing opportunities for women in education, jobs, policymaking, and planning. It’s imperative to take strong measures against those who oppose women’s reproductive rights.

Pakistan stands at a crossroads. Addressing these multifaceted challenges is not just an option — it’s a necessity. The future of the nation depends on it.