August 29, 2024

SEOUL – Song, a 17-year-old high schooler based in Gyeonggi Province, used to be just like any other girl her age on social media — posting photos and short-form videos of herself or with her friends dancing along to trending audio tracks.

That was until she received an anonymous message on Instagram. It still haunts her to this day.

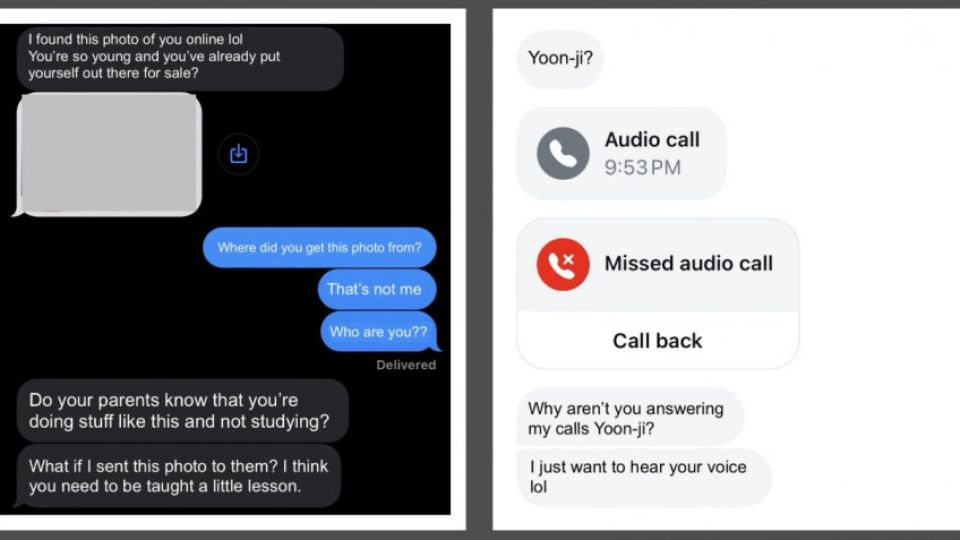

“I looked at my phone after school when I saw a message sent through an unidentified account,” Song told The Korea Herald. “The message read, ‘Do your friends and parents know about this side of your life?’ with an attachment of three photos.”

When Song opened the message, she was shocked to find sexually explicit photos of herself. But these photos were not actually taken of her. They were deepfakes — digitally altered photos almost impossible to tell apart from actual images.

“I was so shocked and terrified when I first saw the photos. Even though I knew they were fake, generated images of me, they seemed so real,” said Song. “I wanted to believe it was just a bad dream that I’d eventually wake up from.”

The messages, however, only continued from there. From messages that questioned whether Song was really the person behind the sexually explicit photos, some demanded Song to “relieve them of their boredom” by asking her to “entertain them.”

“I tried to tell them that it wasn’t me at first. I think I even asked some of them to help me in the beginning because I thought, maybe there’s at least one person that would be the good, helpful adult,” added Song. “But me responding to all their messages seemed to only excite them. The messages kept coming, with their demands worsening daily.”

Growing fear

Song is one of a growing number of victims, many of whom are underage.

According to the Women’s Human Rights Institute of Korea, a total of 2,154 people sought help at the institute’s Advocacy Center for Online Sexual Abuse Victims due to deepfake pornography from April 2018 until Sunday.

Out of the total number of 781 people who sought help at the institute’s Advocacy Center for Online Sexual Abuse Victims due to deepfake pornography this year, 36.9 percent, or 288 people, were minors.

The number of minors who sought help due to deepfakes has also seen an exponential increase in recent years, from 64 in 2022 to 288 this year as of Sunday.

As fear of such a crime utilizing artificial intelligence technology is growing, the Ministry of Education said Wednesday that it would take a firm stance against countering deepfake pornography crimes in schools. Penalties for perpetrators could include expulsion, the highest of the ministry’s nine-tier penalty system for high school students involved in school violence. For perpetrators in elementary or middle school, getting transferred is the maximum penalty as both are considered compulsory education.

As of Tuesday, a total of 196 reports of deepfake sex crimes were reported to education offices nationwide, with 186 of them involving students. The 186 student victims consist of eight elementary school students, 100 middle school students and 78 high school students. Out of the 196, the Education Ministry stated that 179 have been referred to police.

The ministry also decided to operate an emergency task force to respond to deepfake sex crimes from Tuesday. The new group will investigate crimes involving deepfakes on a weekly basis, handle the reports submitted by the victims, provide psychological support to the victims, provide education and increase awareness of such crimes in schools, and strengthen digital ethics and accountability.

Vice Minister Oh Seok-hwan of the Ministry of Education speaks during a press briefing on the ministry’s response to the increasing number of deepfake sex crimes in schools on Wednesday. PHOTO: YONHAP/THE KOREA HERALD

Absence of laws

Deepfake technology has progressed a lot in recent years, with artificial intelligence tools available that enable users to create deepfakes.

However, there is no legal system in South Korea to identify, filter out, and punish those who wrongfully use AI technology.

According to the Act on the Special Cases Concerning the Punishment of Sexual Crimes, anyone who edits, synthesizes or processes deepfake pornography is punishable by up to five years in prison or a fine of up to 50 million won ($37,400). Those who distribute the content for profit are punishable with up to seven years in prison. However, the catch is that there are currently no laws punishing those who download or watch deepfake pornography.

“Currently, the law punishes the act of watching sexually explicit videos taken without consent, but the law is absent for deepfakes,” human rights lawyer Min Go-eun told The Korea Herald. “These days, technology has advanced so much that it’s hard to identify a deepfake from an actual photo or video taken by someone. However, the law still has loopholes in which it doesn’t equate deepfakes with illegally taken images or footage.”

Even if one faces charges for creating deepfake pornography, prosecutors must prove it was for the purpose of dissemination. If there is nothing to show a clear intention to disseminate, perpetrators can “easily find a way out,” Min said.

The National Assembly’s Gender Equality and Family Committee’s Rep. Lee In-seon from the People Power Party on Tuesday said that the committee will “further strengthen” the legal system to prevent the misuse of deepfake technology, with a focus on the loopholes in the Punishment of Sexual Crimes Act.

“The committee will no longer ignore this serious situation. By strengthening and amending relevant laws, we will work to protect women and minors (from digital sex crimes),” said Lee.

People Power Party’s Rep. Lee In-seon from the National Assembly’s Gender Equality and Family Committee speaks during a press briefing on Tuesday on the committee’s goal to further strengthen the legal system against deepfake sex crimes. PHOTO: YONHAP/THE KOREA HERALD

As of Wednesday, up to eight laws have been submitted by lawmakers that call for specific indicators, such as watermarks. to be mandatorily placed when photos or videos are generated with AI to ensure the safety and reliability of AI technologies.

Most were resubmitted after being automatically scrapped due to the end of term for the 21st National Assembly on May 29.

However, these bills also face limitations as deepfakes are often generated with open-source AI models, which make it difficult to determine who used which AI model or algorithm to make them. Open-source AI models can also be customized, making evading specific deepfake detection techniques easier.

“Regardless, relevant laws should be put in place to counter sexual crimes with deepfakes, as the law has not kept up with the current technological advancements,” said Min.

Egocentrism?

“These perpetrators can be seen to be motivated by their cravings to feel a sense of superiority over those who seem ‘weaker’ than them,” criminal psychology professor Kim Sang-gyun from Baekseok University’s Division of Police Administration told The Korea Herald.

“These people normally are seen to have a desire to dominate, manipulate and control those who they deem are easy to handle, to feel a sense of superior power over them.”

“Normally, most people get over their desire to feel superior through normal social interactions. Perpetrators like those involved in creating and distributing sexually explicit deepfake content on Telegram recently are most likely those who have trouble getting over such desires in real life, as they have trouble initiating healthy social interactions,” added Kim.

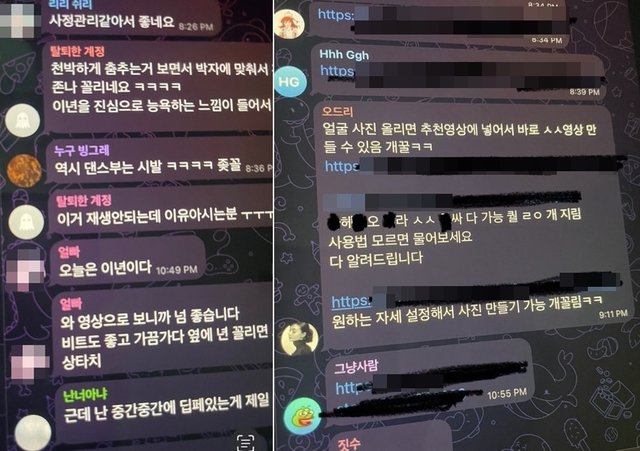

This composite image shows screenshots of Telegram chatrooms related to deepfake pornographic content. SCREENSHOT FROM AN ONLINE COMMUNITY/THE KOREA HERALD

Focusing on underage minors who created and distributed deepfake porn, professor Bae Sang-hoon from Woosuk University’s Department of Police Administration mentioned “adolescent egocentrism,” which is a cognitive and social phenomenon where teenagers in stages of puberty show a desire to show off their strengths, skills and superiority as they believe that others are always watching or evaluating them.

“The minors who are perpetrators of the recent deepfake crimes most likely thought of their actions as nothing more than something that deviates from social norms,” professor Bae told The Korea Herald. “It’s a form of play for them, where they feel like they are better than their peers for trying something so bold.”

Forensic psychologist Lee Soo-jung also added that it is likely that the perpetrators don’t think of their actions as a crime but more of a “thrilling experience.”

“The problem is that these perpetrators who are committing such crimes don’t realize that their actions could be harmful to others. It’s just another way to relieve themselves of their curiosity and interests,” Lee told The Korea Herald. “Proper education methods must be in place to help more people realize this is a crime, not some form of entertainment.”

South Korea’s digital boom has increased convenience but also opened a new realm of serious crime, exploiting anonymity to endanger minors and vulnerable individuals with modern slavery and online sex crimes. The Korea Herald delves into dark digital spaces and efforts to combat these crimes with this new series. This is the third installment.