September 2, 2024

ISLAMABAD – In 2018, Mahmood was an 18-year-old based in Hafizabad [Punjab]. Although he struggled in school, he was good at sports. Because of family pressure, he did not have the option of making a career out of sports.

Mahmood began to feel hopeless. His heart was no longer in his daily activities. One day, a group of friends floated the idea of migrating, to escape his family and life in Pakistan. One of them said he knew a local agent who could help.

The agent told Mahmood and his friends that the journey from Hafizabad to Turkiye would cost a total of Rs120,000. Mahmood did not have that kind of money and had to sell some valuables and save up to collect the rest. His friends did the same. They called the agent, confirming their intent to migrate.

The agent told them to make their way to Lahore. There, they were told to look for a particular agent at a particular bus stop. The agent met them there and took them to a rest house, where they spent the night. In the morning, they were transported to Multan and then Quetta, along with other migrants undertaking the same journey.

Mahmood did not have the entire Rs120,000 on him. The agent had said to carry some cash on them for the journey. The final payment would be made if and when they crossed the border from Iran into Turkiye. To make this final payment, Mahmood handed over the money to a trusted individual, to be transferred to the agent on being notified by Mahmood to do so.

On reaching Quetta, Mahmood was kept in makeshift lodging. As the migrants moved out of Punjab and further along in the journey, he said, their treatment by their handlers became progressively worse.

From this, one can deduce that the smugglers treated their victims well at the start of the journey to secure business. Further along, when migrants’ option to abort their mission dwindled, ensuring their dignity and well-being was no longer a concern for the smugglers.

While waiting at the lodging, another agent came to Mahmood and his friends and demanded money. The friends protested, but the agent threatened to abandon them if the money was not paid.

Recognising that they were now completely dependent on the smugglers, Mahmood and his friends made the required payment.

They were told to wait. Eventually, in the middle of night, a beat-up pick-up truck came to collect them — Iranian vehicles known as zambad, manufactured by Zamyad Co.

Here, different ‘classes’ of travel came into play for the first time. The migrants were told to pay a premium to sit in the front of the vehicle, while the rest travelled in the uncovered cargo bed at the back. Mahmood was able to pay and occupied the back seat of the vehicle. But so did many others. The smugglers crammed in more than 20 migrants in the front, one on top of the other, even filling up spaces on the floor of the vehicle.

From here, a highly dangerous journey started that took them across Balochistan, from Quetta through Duk, further through Siahpat and onwards to Mashkel. The entire stretch of land was as barren as it was dark.

The driver of the zambad sped across rough terrain at over 120 km per hour, with more than 30 people on board. These areas are also known for kidnappings, as migrants carrying cash are easy targets for looters. To evade robbers, and particularly any law enforcement officials patrolling the area, the lights of the zambad were switched off, despite the pitch-black surroundings.

Mahmood feared for his life. Those crammed in the back were pummelled by cold sand-filled winds. They would plead with the driver to allow them to travel up in front, but he would allow this only if they were willing to pay for the privilege.

Mahmood and the rest of his cohort reached Mashkel, where they purchased water and food at exorbitant prices. From Mashkel, the migrants were to cross the mountains bordering Pakistan and Iran on foot. The group, which according to Mahmood comprised mostly men in their early twenties, started the long walk.

Their handler claimed that the walk was only two hours long. In fact, the group walked for close to 48 hours, with barely any food, water or rest. They survived on the few supplies they had brought from home — dates and bread. Not all the members of his group were as physically fit as Mahmood.

Eventually, out of sheer exhaustion brought on by lack of rest, food and water, some members of the group began to fall behind, including Mahmood’s friend. Mahmood, too, fell behind to support him, as he struggled to keep up.

The distance between the main group and Mahmood and his friend began to increase. The Mashkel mountains are vast uninhabited terrain. Getting lost here was akin to a death sentence. Mahmood begged his friend to speed up lest they be left behind, but the latter had almost given up.

Eventually, they lost sight of the main group, but kept walking in the direction of its last-known location. Luckily, the main group had stopped up ahead, allowing them to catch up. At this stage, the group had begun to berate the handler for misleading them about the duration of the journey. Irate, the handler stormed off, leaving them on their own.

They had no idea what to do or where to go. They had run out of food and water and were exhausted. The group started arguing and blaming each other for causing the handler to leave. After about an hour, however, the handler returned, his camel-skin bag filled with water. He told them that he had come back ‘this time’ but, if they created a fuss again, he would leave them to their own devices.

The group resumed their journey. It was soon evident that the Iranian border was nowhere close, and the group would have to continue walking for another few hours. They were out of water. They begged the handler to give them some water; he took payment in return for small sips.

Finally, after several more hours, they hit a road. A container arrived, into which they were tightly packed and taken to a secluded house. They were now inside Iran.

Quite often, migrants entering Iran are captured at the border and deported to Pakistan. There, they face additional abuse by the Pakistani LEAs [law-enforcement agents]. But this risk is factored in at the start. There are provisions in the booking for multiple attempts to cross the border, in case one or more of them are unsuccessful.

FROM IRAN TO THE TURKISH BORDER

At their lodging in Iran, the group had the opportunity to wash up and change if they had spare clothes. The garden in the house had fruit trees, which the migrants plucked and ate from. After their long and gruelling journey, this seemed like an enormous luxury.

Unbeknownst to them, the real test of their resolve was yet to come.

One by one, sedans rolled up and took the migrants away. There was one car for 20 migrants. About five or six of them were crammed into the trunk of the car, while the others were packed into the front and back seats.

According to other reports, migrants at this stage are packed into the luggage compartment of buses, but Mahmood said that his group was transported towards the Turkish border differently.

Mahmood was one of the migrants crammed into the trunk. It was hot and suffocating. He would struggle to breathe, but if they made any noise, the driver would stop the car and threaten to abandon them. The prospect of being left behind now was more serious than before, because they were in a foreign country.

There were multiple check-posts along the way but, just as in Pakistan, the Iranian agents had an arrangement with the local LEAs who gave them safe passage on payment of kickbacks (an observation corroborated by other interviews conducted for this study).

However, if the LEAs were not feeling merciful, or there was an official crackdown in place, one of two things would happen. Either the driver would find a way around the check-post or park the car on the side of the road and order the migrants to run.

Somehow, Mahmood’s driver was able to make his way through all the check-posts and, after several hours, he and his group neared the Turkish border. Once again, they were kept in a lodging where Mahmood saw some migrants being physically beaten.

The migrants were now required to make their final payment before the agents facilitated them into Turkiye. Those who were able to pay were assigned to a handler who helped them cross the Turkish border through the Zagros range. Those who were unable to pay were imprisoned, abused and beaten, until the required money was transferred into the smuggler’s account.

According to reports, those who were still unable to pay were either abandoned or left to the mercy of local gangs, who would extort them for ransom.

After having made his final payment, Mahmood left with his group for the Turkish border. He found the journey through the Zagros mountains considerably harder than through Mashkel. It was bitterly cold and rainy. The group had no cover and their clothes were soaked through. The rocky hills were slippery, and some members of the group slipped and injured themselves. This combination of factors was so challenging that those, like Mahmood, who had not given up hope before, were doing so now.

Eventually, they reached a barbed-wire fence separating Iran and Turkiye. The migrants leapt over but unaware of the fall at the other end, they landed in a ditch, one on top of the other. They helped each other out of the ditch and started walking towards a main road. They were told to wait at a stop for a bus that would take them to Istanbul.

Mahmood and his friends had only booked the journey into Turkiye and not Europe. Therefore, they were not transferred to any onward agent.

TABLE: UNITED NATIONS REFUGEE AGENCY/DAWN

INSIDE TURKIYE AND ONWARDS TO EUROPE

The bus taking them to Turkiye was stopped at a checkpoint. Turkish law enforcement officials realised that the vehicle was filled with irregular migrants. They were taken into custody and moved to a camp.

Mahmood was given some paperwork to fill out and then allowed to leave. Although he could not identify the paperwork specifically, it is likely that he was asked to register as a refugee.

Turkiye is signatory to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees 1951 (the Refugee Convention). It has also passed the Law on Foreigners and International Protection, which establishes the scope and mechanism by which protection is given to asylum seekers. Under this legal regime, migrants can file for asylum protection and, depending on the circumstances, be given either temporary protection or simply a humanitarian residence permit.

Most likely, Mahmood was given the latter, given his status as an irregular migrant and not someone fleeing persecution or fear of persecution.

While many seek asylum, not everyone is able to get it. Numerous migrants are sent back to Iran, where they are mistreated and deported to Pakistan. Mahmood was one of the lucky ones.

Additionally, anecdotal evidence suggests that Turkiye is relatively lenient towards irregular migrants, because it relies on them as a source of cheap labour.

An irregular migrant lives life on the very edge in foreign lands. Unlike Mahmood, some of his friends did not have asylum protection. However, since they were not taken into custody like Mahmood, they made their way into Turkiye and were compelled to survive without any documentation.

This meant that any situation that required documentation could lead to deportation — even falling sick or getting injured and having to go to the hospital.

One of Mahmood’s friends was stabbed on the streets of Istanbul, for example. His friends did not call an ambulance for fear of alerting the authorities and risking deportation. They placed the injured friend on the pavement, moved away and waited for an onlooker to notice the bleeding man and call an ambulance. A passerby called an ambulance and Mahmood’s friend was transferred to a hospital.

While the friend was undergoing treatment, the hospital realised he was undocumented and alerted the authorities. On being discharged, the police were waiting for him. He was asked to go home and gather his belongings.

But the friend did not want to be deported back to a country he had struggled to escape. He contacted an agent and left for Italy overnight through the Mediterranean Sea. His boat was seized twice and returned to Turkish shores. His third attempt was successful; he was fortunate that the boat did not capsize.

Others before and after him have not been so lucky.

UNDERCOUNTED NUMBERS

Human smuggling remains very poorly documented. Statistics have not kept up with the rapid rate at which the issue is growing.

According to some estimates, between 600,000 and 800,000 irregular migrants cross international borders annually. However, researchers consider this a gross underestimate; the actual figures are projected to be in the millions.

There are no reliable global statistics on the number of migrants smuggled on a yearly basis, because of the clandestine nature of operations. Figures are usually based on those migrants that are caught crossing a border illegally. Those migrants that make it across remain largely undocumented. Further yet, irregular migration will continue to rise due to global unrest, porous and unmanageable borders, and the evolution of technology and transportation.

On a domestic level, the figures are even more uncertain, with no credible data available. According to investigative filmmaker Syed M. Hassan Zaidi, who has produced a BBC documentary on the issue of human smuggling from Pakistan, sources on the number of annual irregular migrants are not authentic, and the Federal Investigation Agency’s (FIA) data is particularly questionable.

Independent estimates suggest that about 35,000 irregular migrants arrive monthly in Duk, Balochistan, alone for onward migration to Iran, Turkiye and Europe. Closures on the Afghanistan-Iran border mean that those Afghans who wish to migrate illegally into Iran, do so through Balochistan.

Due to the variables and complexities involved, an accurate figure cannot be provided, but it is fair to make a calculated estimate of between 80,000 and 100,000 annual irregular migrants from Pakistan.

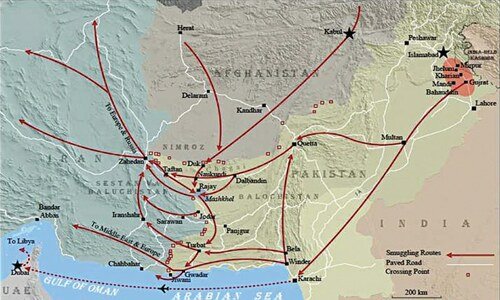

MAP: DAWN

POPULAR ROUTES

Most irregular migration from Pakistan takes place through Balochistan, due to its vast open spaces and relatively porous borders with Iran and Afghanistan. Most migrants hope to reach Europe.

The interviews carried out for this essay indicate that the Naukundi route is the most popular option. This originates in central Punjab and goes through Multan, Quetta, Dalbandin and, then eventually, into Iran through the Taftan border.

Alternative popular crossing points into Iran are in Jodar, Rajay and Mashkel (Balochistan). The map shows some of the popular routes and crossing points for irregular migration from Pakistan.

The routes described above are all land-based.

Sea-based irregular migration also remains a popular option. For this, irregular migrants first make their way to Gwadar, via the coastal highway from Karachi. From there, they are loaded on to boats for onward travel into Iran, Turkiye and Europe.

Irregular migration through this route bypasses the insurgency-hit areas of Makran in Balochistan.

The sea-based route described here originates from Pakistan and goes through the Arabian Sea. Incidents of boats capsizing off the coasts of European countries occur in the Mediterranean Sea during a leg of the journey that usually involves travel from Turkiye to Europe by boat.

For instance, in September 2014, at least 500 people died when a boat carrying smuggled migrants capsized off the coast of Malta. The boat left Egypt on 6 September and sank five days later.

THE BUSINESS OF HUMAN SMUGGLING

The human smuggling business in Pakistan has its roots in legal migration facilitated by the UK [United Kingdom] in the 1950s. In exchange for the displacement of people caused by the construction of Mangla Dam and recognising its need for industrial labour, the UK granted work visas to residents of Mirpur in Azad Jammu and Kashmir.

In the 1970s, residents of Jhelum, Kharian and other neighbouring districts in Punjab also began applying for work visas to move to European countries. By the 1990s, however, Europe was no longer in need of additional labour and, with anti-immigrant sentiment picking up, fewer and fewer work visas were being issued to Pakistani citizens.

This is when individuals began resorting to human smuggling networks to reach Europe through irregular channels. The sections below describe the mechanisms by which smugglers conduct their operations.

NETWORK MODEL

Human smuggling networks are a vast and complex web. Worldwide, it is estimated that 80 percent of all migrants who reach Europe through the Mediterranean Sea enlist the services of a human smuggler at some point.

A given smuggling network will comprise agents across the entire route. For example, in Pakistan, for the land-based route through Balochistan, agents will be based in Gujranwala, Multan, Quetta, Mashkel, Iran, Turkiye and Greece.

As migrants move along the route, they are transferred from one agent to another. The unique characteristics of the network depend on the mutually dependent relationship between agents, which allows operations to be carried out seamlessly.

The names of migrants are shared via WhatsApp from one agent of the network to another. The migrants are told to look for a particular agent on reaching their next stop. The agents all operate under false names. The movement of migrants along the routes are facilitated by sub-agents, who also play a role in recruiting new migrants for a cut of the profit.

The highly organised and structured operations of human smuggling networks rival those of criminal enterprises or mafias. As an indication of their gang-like behaviour, investigators looking into the issue of human smuggling have even received threats, warning them to cease their investigation, according to filmmaker Syed M. Hassan Zaidi.

The human smuggling network is a self-perpetuating cycle, where many former migrants become smugglers. This is for two reasons. First, the element of trust and solidarity is key in such operations. Smugglers are more likely to be trusted by those they have handled in the past and who understand smuggling operations. Second, migrants are lured into the network by the promise of quick cash and the prospect of moving their own families out of Pakistan, just as they themselves did in the past.

In this manner, migrants reaching Turkiye or Europe make short videos reviewing their smuggling experience as positive. Agents back in Pakistan then use those video clips to attract more victims.

ROLE OF THE FIA

Section 11 of the Prevention of Smuggling of Migrants Act 2018 authorises the FIA to investigate and crack down on human smuggling. A detailed list of obligations of the FIA is provided in the accompanying Rules [in the main report].

According to Rule 9, the FIA is responsible for conducting timely and independent investigations, ensuring the immediate safety and security of migrants, safeguarding the rights of migrants, identifying organised networks, and detecting illicit financial flows of money. In practice, however, the FIA is often complicit in the entire process.

According to investigative reporter Akbar Notezai, considering the variables and actors involved and the complexity of the process, a transnational operation of this magnitude would not be possible without the knowledge of the FIA. Officials look the other way in exchange for a share of the profit.

This explains why smugglers are arrested in large numbers only after a nationwide crackdown is announced, such as that after the June 2023 fishing boat disaster in the Mediterranean Sea.

At other times, their network continues to operate with impunity.