February 4, 2025

MANILA – “I don’t know why I keep thinking about fire—about pyromes, fire biomes, ecosystems shaped and scorched by flames. Maybe it’s because I’ve seen with my naked eyes the devastation,” says Isola Tong in conversation with Kevin Corcoran.

Born in 1987, Tong has established herself as a research-based interdisciplinary artist whose work explores the complex intersections of ecology, queerness, and postcolonial geographies. Through diverse mediums including sculpture, performance, installation, and workshops, she investigates how landscapes carry both material and metaphorical narratives shaped by colonial histories, climate change, and political forces.

Isola Tong is an artist, designer, writer, theorist and educator who graduated from the University of California, Santa Cruz with an MFA in environmental art and social practice. PHOTO: PHILIPPINE DAILY INQUIRER

“Bruha ng Disyerto”

Lately, Tong has been sparking discourse in her ongoing exhibition at Gravity Art Space, “Bruha ng Disyerto: Landscapes of Fire,” running from Jan. 17 to Feb. 14, 2025.

The fires in California are a pressing issue that has devastated many and hit close to home for others. Tong weaves this narrative of fire across landscapes in California and the Philippines, transforming her metaphor of the desert witch into a symbol of the “estrangement of people and (agri)cultural practices from the land by colonial forestry under Spain and the United States” (Gravity Art Space exhibition notes).

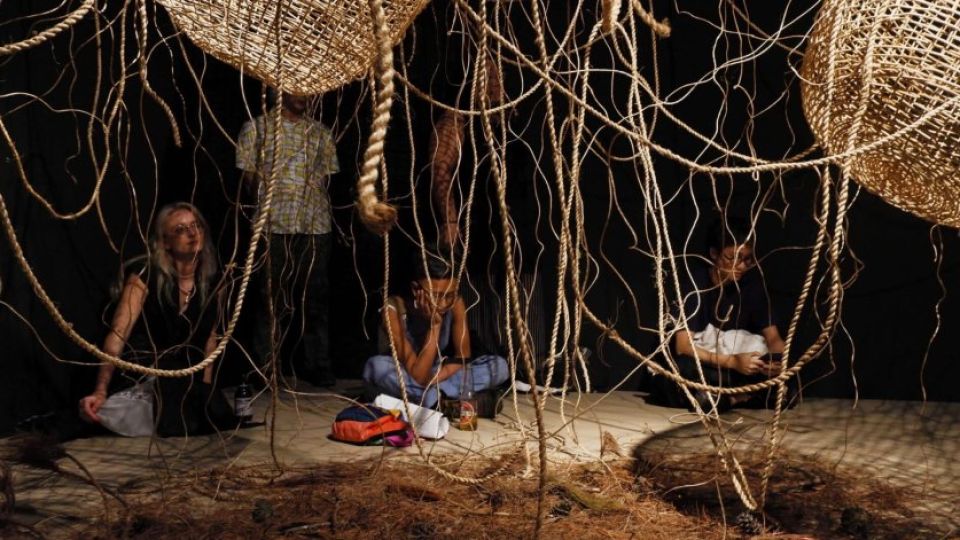

Isola Tong, ‘Pugad (Nest A)’ rattan, abaca, pine needles (Pinus Kesiya, Baguio), dimensionv variable, 2025. PHOTO: PHILIPPINE DAILY INQUIRER

Tong’s projects demonstrate a focus on fire-affected geographies, as she examines flame’s dual nature as both a destroyer and a regenerator. Her practice incorporates traditional craft techniques, especially basketry, as a storytelling medium. Working collaboratively with communities, she creates pieces that incorporate ash and charred materials, weaving together narratives of care, ecological justice, and kinship.

READ: Chappell Roan: The splashy pop supernova

Indigenous references

The artist writes moving prose in her notes titled “Their Blackened Arms Still Rise Skyward as if in Surrender.” Citing her personal experience in the Mojave Desert, she remembers petroglyphs and land formations that sparked insight. She walks viewers through her own experience, discussing her visit to the Cima Dome, where 800,000 Joshua trees were scorched by wildfires.

Looking back at history, Tong tells the story of how in the 1800s, settlers arrived in the Mojave Desert, driving out the Indigenous Chemehuevi people and, in the process, their knowledge of fire management in a landscape vulnerable to fires.

Isola Tong, ‘Benguet Fire’ pyrography on banig, textile, acrylic medium, 46 x 94 cm. 2025. PHOTO: PHILIPPINE DAILY INQUIRER

Linking real life to mythologies, she interprets the Chemehuevi creation myth of Coyote and Wolf. In the story, as recounted in her exhibition text, Coyote receives a basket from Old Woman containing people. When Coyote opens the basket in the desert, people scatter in all directions. However, at the bottom of the basket lie broken and crushed people who were forgotten.

Rather than abandoning these people, Coyote seeks help from Wolf, who heals these broken individuals and teaches them survival skills. Tong lauds how these people in the myth ultimately became stronger than those who first fled, learning to thrive in the harsh desert environment the others had rejected.

Isola Tong, ‘Sanga’ rattan, ink, 250 x 45 x 25 cm. 2025. PHOTO: PHILIPPINE DAILY INQUIRER

READ: New Deo Gracias menu is a special invitation to linger, sobremesa-style

The story acts as a metaphor in her own work, particularly as she reimagines Old Woman as a “trans creatrix who births new worlds and nurtures new life.” The basket then becomes a symbol of “Bayotic Refugia,” an intriguing term Tong has coined. The neologism combines “bayot,” the Bisayan term for queer or femme, with “biota,” which refers to all the plant and animal life in a region. Meanwhile, the basket itself becomes a refuge where broken life can heal and regenerate in the oppressive environments that are so timely today.