February 12, 2025

MANILA – In 2022, Paul (not his real name), a 27-year-old IT dropout, worked as an online bet collector at Philippine offshore gaming operators (POGO) in Makati. When President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. banned POGO operations in late 2024, Paul was one of the hundreds of Filipinos who lost their jobs in the country’s gambling sector.

On September 15, 2024, Paul discovered a job offer on Telegram, an online messaging app widely used for podcasts and job recruitment. Without a job and with a promise of a lucrative salary in Thailand, Paul grabbed the opportunity.

“The recruiter did not ask for a placement fee,” he said.

Meanwhile, the couple Boyet and Linda (not their real names), were former OFWs in Saudi Arabia. After their contracts ended, they found a job in the UAE. After eight months, they resigned from their jobs as household workers because their employer could not pay their salaries anymore. The couple also found out that their agency was operating without a permit.

READ: BI logs increase in trafficking cases linked to catphishing

Like Paul, they were recruited to work in Thailand as customer service representatives. Cash-strapped and jobless, the couple accepted the job offer since there was no placement fee.

A recruitment flyer. PHOTO: COLLECTED/PHILIPPINE DAILY INQUIRER

“Mikaela was our recruiter. We met her in the UAE. She was the HR of the company where we were supposed to work,” Linda said.

Mikaela was said to freely move between the UAE, Thailand, and the Philippines to recruit workers.

From the UAE, Boyet and Linda were flown to Bangkok, arriving on August 1, 2024.

READ: BI referred over 990 human trafficking victims to IACAT in 2024

‘Backdoor’

Paul and eight of his companions — nine males and five females — used the backdoor to leave the country.

“We traveled to Balabac Island in Palawan. From there, we took a boat to Sabah, Malaysia. The agent took our passports,” he narrated.

This process is called “chop chop” — in which their passports have exit and entry stamps, but there are no records in the immigration database.

The group stayed in Sabah for two days while waiting for their passports. They traveled by car to Kota Kinabalu and then boarded a plane to Kuala Lumpur. From Kuala Lumpur, they took a bus going to Penang, and finally reached Hatyai in Southern Thailand, where they were flown domestically to Bangkok. It was only on the Thai side that they entered legally.

Paul also mentioned that there were 17 Filipinas who arrived in December via the “legal” route.

They claimed they had a contact at the Bureau of Immigration at Ninoy Aquino International Airport (Naia). Among all the interviewed Filipinos trafficked to Myanmar also claimed that certain immigration officials at Naia did not ask them any questions or request their documents.

Route to Myanmar

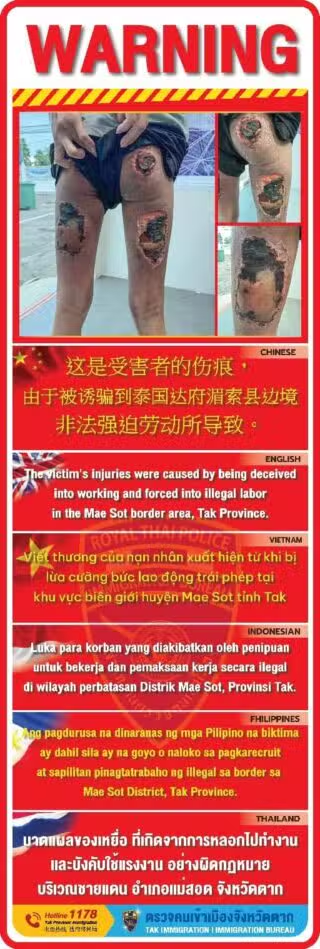

The main route for trafficked Filipinos to Myanmar is via Thailand, where a Chinese agent from the alleged scam company would pick them up from the airport and bring them to Mae Sot, Thailand’s border town with Myanmar. Then, they would cross the Moie River bordering Mae Sot and Myawaddy.

Warning poster about scam centers. PHOTO: COLLECTED/PHILIPPINE DAILY INQUIRER

They had neither a departure stamp from the Thai immigration nor an arrival stamp from the Myanmar immigration — thus illegally crossing the borders.

Paul and his companions started working in KK Park in Shwe Koko as soon as they arrived on October 11. Boyet and Linda, who arrived earlier, were in KK Park 2, allegedly under the X-Max Group of Companies. KK Park is a collective name for the complex known as the major hub of internet fraud and human trafficking.

When they arrived in Maesot, Boyet, and Linda knew that they too had been “scammed.” But it was too late to back out — they did not have money and the guards were heavily armed.

Modus

The scam centers have different operations. There are dating, gambling, and investment sites.

The workers find their potential “clients” through social media, particularly X accounts verified by Meta. They choose “clients” based on what they post on social media. Their clients range from bankers, managers, retirees, and other professionals of all ages.

“There is a finder and a chatter,” explained Boyet.

All of them, however, can be a finder and a chatter. If they can manage to attract investors, the scammers would get a financial reward.

They pose as European women, depending on their target victims’ preferences. Some even pose as Asians. The identities they use are usually taken from Instagram users with open accounts. Once a relationship is established, the “woman” encourages the target to invest in crypto. The investment can be wired or transferred as USDT (US Dollar Tether, the crypto equivalent of the US dollar) to a digital wallet and transferred in a platform which is the Forex market.

When the clients ask for a video call, deepfakes generated by AI from stolen identities would speak with them. They also have a Filipina model to speak with them. According to Boyet, this Filipina shows her body or does whatever the client asks her to do.

Photos of abuse at scam centers. PHOTO: COLLECTED/PHILIPPINE DAILY INQUIRER

Pay or escape

Paul could no longer endure the difficult situation and was bothered by his conscience. Some of his companions were sold to other companies and experienced beatings and abuses when they could no longer reach the quota. He was also sold to another company despite paying P270,000 for his release.

The families of the human trafficking victims (HTV) pay via USDT to evade tracing.

Despite his ordeal, Paul never gave up. He started befriending the Karen guards in the compound despite his limited ability to communicate. He also observed the routes and guard rotations. At this time, he was already communicating with Col. Dominador Matalang, the police attache of the Philippine Embassy in Thailand.

In the early morning of February 6, Paul was able to escape, following the route via Google Maps provided by Colonel Matalang. Paul said that he walked through farms, asking for directions from the Burmese people he met along the way.

Finally, he reached the river where he asked the boatman to help him cross the border to Thailand.

Boyet and Linda were laid off by the scam company in early January — although they still have three months to work based on their contracts. Instead of paying, the couple opted to just pay for their freedom from the salaries they were supposed to earn. Each of them paid $1,500. They reached Thailand on January 31.

The three Filipinos are identified as HTVs under the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) and are presently undergoing counseling in a shelter in Chiangrai. Since Boyet and Linda are couple, they stay in the same shelter.

Under the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) process, the potential HTVs will undergo an initial interview at the immigration to determine their eligibility for the NRM. If deemed eligible, they will be referred to the Anti-Human Trafficking Victims Identification Center in Maesot.

While processing, the Thai authorities are communicating with the respective embassies of the HTVs for the repatriation.

The final interview will be conducted by the Multi-Disciplinary Team. If they are qualified and identified as HTVs, they will be transferred to shelters — the women to Pitsanulok and then men to Changrai – where they will undergo counseling. If not, they will appear in a Thai court and will be detained in an Immigration Detention Center (IDC), fined, and deported.

Filipinos in scam centers

According to Colonel Matalang, there are still approximately 500 Filipinos trapped in scam centers in Myanmar.

The Civil Society Network for Victim Assistance in Human Trafficking claims that as of January 2025, there are over 6,000 HTV from 21 countries including Bangladesh, Brazil, Burundi, Ethiopia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Japan, Nepal, South Africa, Kazakhstan, Laos, Thailand, Russia, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, and South Africa. Half of those HTVs are from China.

Thai government imposes sanctions

The Thai government has already imposed sanctions on Myawaddy. Starting the last week of January, power, fuel, and internet were cut off to five communities in Tachileik, Myawaddy, and Payathonzu border regions of Myanmar, in their effort to stop the operations of scam centers.

According to a Bangkok Post report, there was also a crackdown on the smuggling of fuel and solar panels to the border towns of Myanmar.

The Filipinos left in the scam centers are hoping that as the Thai sanctions progress, they will be freed soon.