February 13, 2025

DHAKA – These days, I witness a lot of societal fulminations on the directions and goals of our foreign policy. Having been an active practitioner for almost four decades and a continuing interested observer for well over a decade, I am not a little disturbed at some of the things I hear. Perhaps I hear incorrectly, but what I worry about more is that the external actors with whom we maintain interstate relations may also be hearing, and misinterpreting, as incorrectly as I.

A few years ago, I wrote in The Daily Star, “A fundamental dictum in foreign policy formulation and analysis is unquestionably this: each country, as a sovereign, independent nation-state, contextualises its every move or action within the overall rubric of preservation and advancement of its own national interest. Therefore, each party, in any bilateral relationship, must acknowledge and be fully conscious of these mutual constraints, and also respect ‘where’ the other party is coming ‘from.’ It takes two to tango, as they say, and if each dancer in performing this very difficult and complex choreography is not in tune, innately, with the partner, a misstep or miscue would end in serious accident or injury to one or both.”

Writing in the annual Journal of the Bangladesh Foreign Service Academy last year, I asserted that our foreign policy configuration must be “buttressed by a hard-nosed pragmatism and understanding that while one may choose one’s friends, one cannot choose one’s neighbourhood; and that while friendship may exist between peoples and persons (which even then are vulnerable to change), ‘friendship’ between states is primarily driven by the national demands of each state, rendering such friendship very protean in nature.” In this context, friendship between states may best be described as being the state of relatively happy equilibrium between two or more states that have managed to arrive at a mutually acceptable alignment or coexistence of their national interests that serves everyone in perceptibly equitable measure.

When formulating the parameters of foreign relations with other states, whether far or near, there are several essential factors that need to be considered.

First, geography matters. It encompasses geolocation, geomorphology, and geopolitics.

Second, size matters. It alludes to the physical size in terms of land (and water) areas in possession. It also, importantly, alludes to the size of population, combined military capacities, economy including GDP and GDP per capita, and the state of technological advancement.

Third, perception matters. This not only encompasses how the governments of interacting states perceive each other, but also how the domestic population of each state views its governments or governments of other states, near or far from it.

All of the above are variables with their own subsets. They comprise a complex mix that can be volatile and subject to spontaneous combustion by the slightest spark. We can address these either with viscerally charged, emotionally soaked jingoism, or cool-headed rationality standing with feet on the bedrock of pragmatic realism.

The world we know has witnessed two World Wars in the last century. Each ended with global political geography being changed, ending the status quo ante. Former empires crumbled; new states were formed while some were broken apart. Ironically, the Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I generated the drivers for World War II. The Wilsonian idealism that eluded the closure of World War I was brought out of the woodworks after World War II, putting in place institutions and building blocks of what was touted by the Allied victors as the “New World Order.” The basic unit comprising this new order was the state, which was to be looked upon by all others as being equal in the “comity of nations,” their borders hard, impermeable and inviolable, their sovereignty supreme, not brooking any interference in their internal affairs.

The superpowers that emerged set up the new international financial institutions and rules through putting in place the Bretton Woods system. They set up global institutions like the United Nations and its General Assembly and numerous organs like the International Court of Justice (ICJ), or much later the International Criminal Court (ICC), the Human Rights Commission, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and so on.

While the UN was set up with the loftily stated ideal of preventing any repetition of the scourge of war, a goal that was to be ensured by the UN Security Council, the most powerful entities of this so-called New World Order have been the instigators or supporters of most wars or conflicts after 1945. While the most powerful are supposed to safeguard a rules-based world order, the last decade has shown that the principles of inviolability of borders, state sovereignty and non-intervention in the internal affairs of the state are flouted, egregiously, by the most powerful of states.

We appear to be already in the early throes of a World War III, with principles of state “sovereignty” and state borders being “inviolable” being rendered figments of the imagination. The mighty can impose their wills on anyone they please, and change borders and lives of settled peoples at their will. The UN, the ICJ, The ICC, and the WTO have all proven to be made of clay. Political geography in former Eastern Europe and Middle East are already being reconfigured from their hitherto accepted positions since 1945. The only overriding principle of inter-state relations today appears to be increasingly the axiom “Might is right.” All prior agreements, supposedly inviolable, can be revoked at will. All smaller, less powerful states, anywhere or everywhere, have never been more vulnerable and fragile than they are today.

In such a situation, what should Bangladesh do in what is obviously a far more hostile world today than what existed at the time of its birth, almost five and a half decades ago?

At a recent gathering at the Foreign Service Academy, our foreign affairs adviser asserted that Bangladesh seeks friendship with all countries and does not want to take side with any one country or power against any other. He was absolutely right.

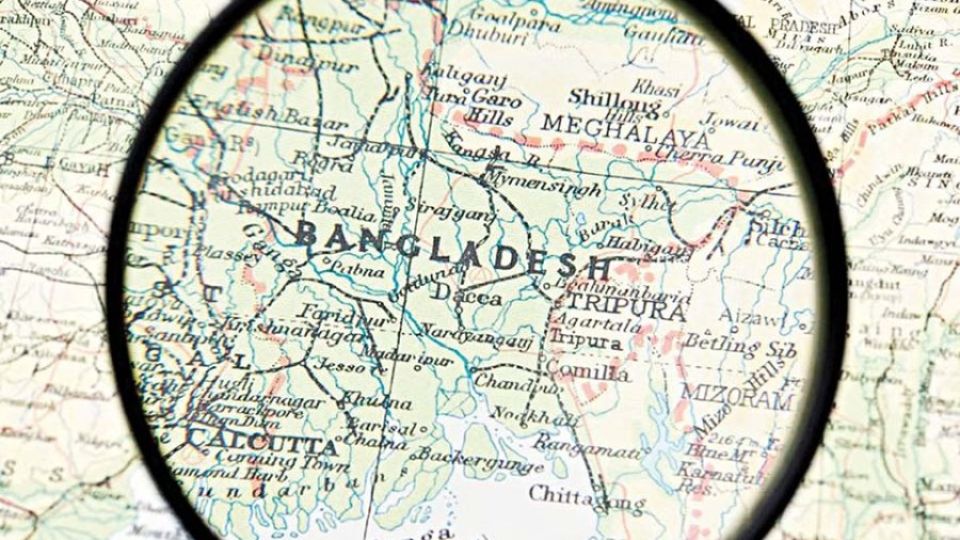

Bangladesh must look at the map of Asia and its own geomorphological location in that. It is almost entirely surrounded by India, which controls all rivers as upper riparian. It is “spitting distance” away from China, the Asian giant aspiring to superpower status and already the second largest economy in the world. By virtue of its propulsion of being at the epicentre of our oceanic planet, with the Bay of Bengal where it is centrally located bridging the Indian Ocean with the Pacific Ocean, Bangladesh finds itself in the strategic crosshairs of competing (or contesting) global powers, located near or far. Its socioeconomic vulnerabilities and the aspirations of its largely youthful population, demanding better lives and opportunities for themselves, necessitate that we must stay out of geopolitical conflicts that will derail our development efforts. Internal internecine factional strife will be self-defeating, even self-destructing.

We must endeavour to develop friendly, mutually beneficial cooperation with all nations, whether they be our immediate neighbours or near neighbours, whether to our east in Southeast and East Asia, or to our west in South, Southwest and Central Asia, without exception.

We must at the same time strive to have peaceful, friendly and mutually beneficial cooperation with all powers, in Asia, Africa, Europe or Americas, regardless of whether those powers behave with each other in terms of friendship or animosity. Ours must be a policy not of isolation with anyone, nor seeking confrontation with anyone, but living in peace with all and promoting peace among all.

Since the earliest times, at least from Fourth Century CE, our location in the Bay of Bengal propelled us to become the richest region, or Mughal suba (province), Colonial British India’s presidency. That enabled all the countries of the Bay of Bengal region to comprise a living, thriving, prosperous integrated economic region that invited global covet and respect. World War II fragmented that hitherto regional integration, just as it fragmented our own subcontinent.

We must now collaboratively strive to work with our Bay of Bengal neighbours to ensure that our Bay, from which we derive our identity and historical legacy, remains a zone of peace, neutrality, prosperity and friendship, serving once again as it did in the earlier times as the highway for peaceful interlocution between states and peoples, inclusively, whether in the Eastern or Western Hemisphere. We should strive to be a catalyst for fashioning a fraternity for the Bay of Bengal Economic Cooperation.

Bangladesh is like a walnut, caught in the jaws of two nutcrackers in today’s world. One nutcracker is regional, comprising the competing jaws that are India and China. The other nutcracker is global, its jaws comprising the US-led Indo-Pacific narrative facing off the China-led BRI. We must be with both, without being against either. The shell of the walnut gains its strength and firmness from within, and so must we, through developing internal resilience.

Within South Asia, we must champion better relations and cooperation with all countries, from Afghanistan to Sri Lanka, even if some of them have indifferent or even hostile relations with each other. Their fights should not be our fights, but our peace and friendship must also be theirs to emulate. Our policy must strive to tread the razor-edge path of “strategic autonomy”that walks with “active neutrality.”