March 17, 2025

DHAKA – We are what we breathe. Now imagine that breath—something we do without thinking—could be quietly slashing years of our lives. That’s no idle fear: air pollution claimed 8.1 million lives in 2021 alone, roughly one in every eight deaths worldwide and one in three in South Asia, according to the latest Global Disease Burden report. It’s the second deadliest health risk on the planet, trailing only high blood pressure, and it spares no one.

The threat comes in two forms: the polluted air filling our streets and the smoke lurking indoors from cooking fires or dusty homes. Over 90% of us breathe air so toxic it acts as a slow poison, says the World Health Organization. Tiny particles—PM2.5—slip past our defenses, wreaking havoc: 48% of chronic lung diseases like COPD tie back to this particulate matter, while 34% of preterm births in 2021—babies arriving too early—link to the air mothers breathe.

Dhaka has some of the deadliest air pollution in the world. Routinely among the world’s most polluted cities, its air is a stew of brick kiln soot, exhaust fumes, construction dust, and factory emissions, whipped up by runaway urban sprawl. Recent reports show its Air Quality Index (AQI) often topping 200— “very unhealthy”—a daily gamble for lungs and hearts. The Clean Air and Sustainable Environment (CASE) project tracked the toll: In 2018, 75% of days were unfit to breathe. Even in 2020, over half stayed hazardous. For millions in Dhaka, it’s coughs that won’t quit, cancers that bloom silently, and hearts that give out too soon.

In 2024, Dhaka ranked 13th among the most polluted global cities based on AQI-US standards. This year, in January and February, Dhaka consistently ranked first in the list of most polluted global cities for 11 days when AQI exceeded 243, with the highest of 392 on February 10, 2025, surpassing even Delhi and Lahore, two of Asia’s most polluted cities. From 25th January 2025 to 23rd February 2025, IQAIR data shows Dhaka’s air was unhealthy for 18 days, very unhealthy for 15 days, and hazardous for 1 day. During this period, the average AQI of Dhaka City was 203, and the average PM2.5 concentration was 124 µg/m3. This PM2.5 concentration is eight times the 24-hour standard (15 µg/m3) and 25 times the annual standard (5 µg/m3) set by the WHO.

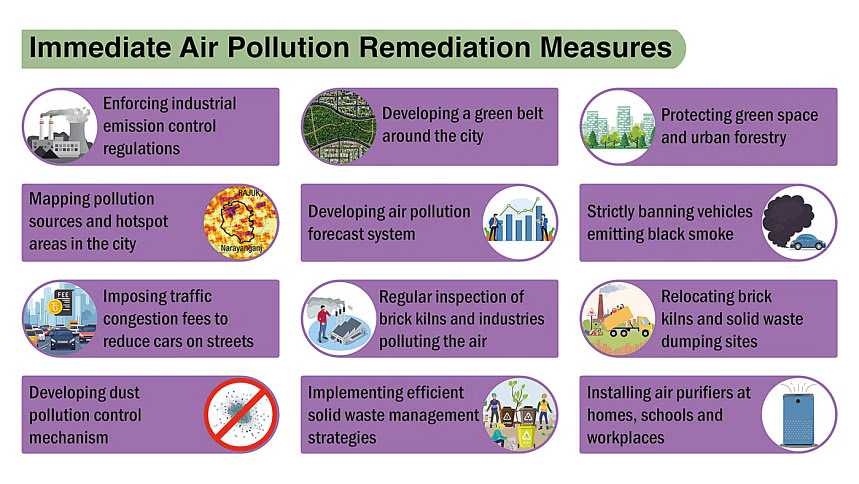

Immediate measures to improve Dhaka’s air quality. SOURCE: BENGAL INSTITUTE

The biggest polluters

It is critical to pinpoint the sources of air pollution correctly. When it comes to pointing out the causes of Dhaka’s toxic air, most reports and features attribute it singularly to the brick kilns surrounding the city. While brick factories play their part, the actual causes remain largely unexplored due to a lack of comprehensive research. National and international studies provide valuable insights into how different sectors contribute to Dhaka’s air pollution. For example, a survey by the Norwegian Institute for Air Research (2015) identified industrial emissions, transportation, and fossil fuel combustion as the primary culprits behind the city’s toxic air. The report reveals that these three sectors together release 19,000 tons of Particulate Matter (PM2.5) into Dhaka’s air annually, with industries alone contributing 17,556 tons of PM2.5 each year. Industries are also the leading source of Sulfur Oxide (SOx) emissions, releasing around 60,000 tons annually. Additionally, transportation is the major emitter of Nitrogen Oxides (NOx), at 7,500 tons per year, followed by industries at 2,000 tons. In terms of Carbon Oxides (COx), transportation (18,450 tons/year) and fossil fuel combustion (12,350 tons/year) are the dominant sources.

Another report, the Bangladesh National Air Quality Management Plan 2024-2030, identified six sectors of PM2.5 pollution in Dhaka City: household combustion, power plants, brick kilns, solid waste, road dust, and transport. Among these, household combustion contributes the most (28%) and transport the least (4%), according to the document. The report states that brick kilns contribute only 13% of Dhaka’s total PM2.5 pollution, yet surprisingly, it does not mention industrial emissions at all.

A significant discrepancy shows up when comparing the two studies. While the Norwegian study identifies industry as the major contributor to PM2.5 pollution, the national report attributes the largest share to households. Additionally, the national report does not provide data on gas pollution, and neither report accounts for ozone pollution. These discrepancies and gaps highlight the urgent need for a comprehensive study.

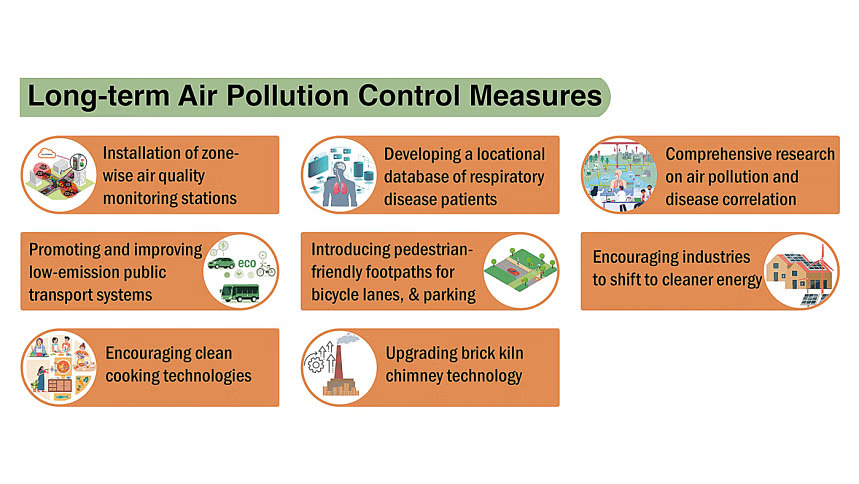

Long-term initiatives to reduce Dhaka’s air pollution. SOURCE: BENGAL INSTITUTE

Seasonal patterns of pollution in Dhaka’s air

Air pollution in Dhaka also exhibits seasonal variability, with significantly higher levels in the winter months (December–February) and lower levels in the monsoon season (June–September). However, in the summer and post-monsoon seasons, although the levels of particulate matter and gases remain lower than in winter, they still exceed air quality standards set by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Bangladesh’s National Air Quality Standards. A similar seasonal pattern can be observed in other major cities nationwide.

Weather phenomena and the intensity of human activities influence the seasonal fluctuations in air pollution. In winter, limited rainfall, increased construction activities, and sporadic sand filling are the primary contributors to elevated pollutant levels in Dhaka. Additionally, northwestern winter winds carry transboundary pollutants and smoke from brick kilns in northern and northwestern Dhaka over the city, pushing air quality to highly toxic levels.

During this period, not only does particulate pollution increase, but the emission of toxic gases—such as NO2, SO2, CO, and O3—from proliferated industries in the city also reaches its peak concentration in the air. However, as the monsoon begins in June and continues through September, heavy rainfall reduces the levels of both gases and particulate matter in Dhaka’s air, slightly improving air quality and making it breathable.

Despite slightly better conditions during the monsoon, ground-level ozone (O3) concentrations remain elevated in summer due to reactions between NO2, emitted by vehicles and industries, and ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun. This lower atmospheric Ozone (O3) is particularly harmful to individuals with respiratory conditions. Satellite-based analyses by the Bengal Institute reveal clear seasonal trends in the concentration of major pollutants in Dhaka and its surrounding areas.

Proliferation of brick kilns in and around Dhaka City

Brick manufacturing in and around Dhaka City continues to be the most cited polluting culprit. While in 1990, there were around 250 brick kilns in the proximity of the city, the number grew three-and-a-half-fold in 2000, driven by the increasing demand for construction projects. Over the past two decades, the number of brick kilns surged to around one thousand. These brick kilns now encircle the city along the five rivers: Buriganga, Turag, Dhaleswari, Shitalakhya, and Bangshi. The availability of suitable textured soil, extensive open lands, easy waterway transportation, and increased city demand are key factors for their locational developments.

Recent satellite imagery analysis by the Geographic Research Unit of the Bengal Institute identified 389 operational brick kilns within the RAJUK boundary of Dhaka, with an additional 600 kilns located within 20 kilometers of the RAJUK area.

Smoke containing NO2, CO, SO2, and particulate matter (PM) from coal combustion in these brick kilns, especially during the winter months, is carried over Dhaka City by the northwestern winds, leading to a significant deterioration in Dhaka’s air quality.

Transboundary air pollution transmission

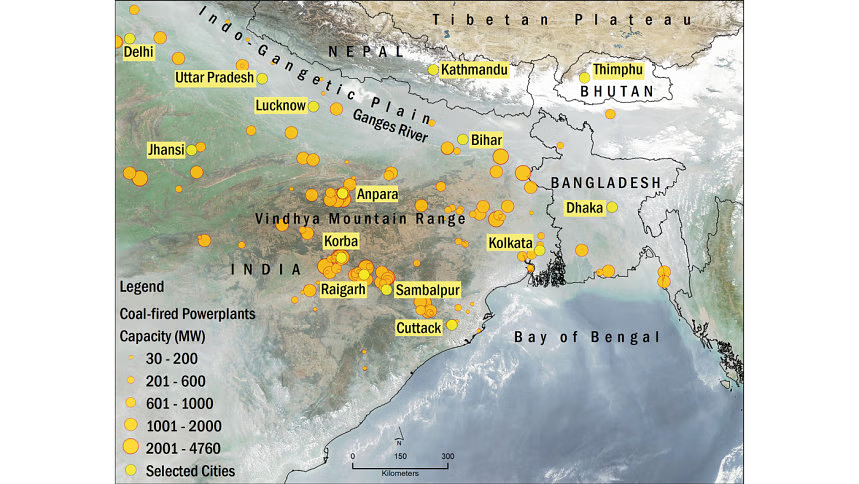

Not all of Dhaka’s air pollution originates within the city itself. During the period from late October to December, the great Indo-Gangetic Plain (an area of 700,000 sq. km.) experiences a dense cloud of smoke in its air, mainly due to stubble burning. Farmers in northern India burn paddy straw after harvesting rice, causing this extremely polluted air, mixed with smoke and particulates, to engulf the densely populated plain, covering Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Bangladesh. The cloudy haze over this region is also contributed by more than 100 coal-fired power plants operational throughout the year in northern India. Some studies confirm that Delhi’s Air Quality Index (AQI) exceeds 400 during that time, which requires shutting down academic institutes and calls for people to work from home.

An article published by the World Bank on February 3, 2023, says that around 30% of the pollution in Bangladesh’s bigger cities originates in India. As winter sets in, the northwestern wind carries fine-particle-laden smoke from the extensive Indo-Gangetic region of India towards the southeast, which at that time looks like a river of haze following the Ganges River’s flow direction towards Bangladesh. This massive cloud of dust spills out into the Bay of Bengal, crossing the entire sky of Bangladesh.

REMEDIATIONS AND MEASURES: WHAT WE CAN DO

Given Dhaka’s persistently hazardous air pollution, remediation is neither straightforward nor quick. Addressing air pollution requires coordinated efforts from the government, industries, businesses, and citizens. While various measures must be implemented across multiple sectors with both short- and long-term goals, the ultimate responsibility lies in comprehensive urban and regional planning that prioritizes the health and well-being of the city’s residents. Below is a summary and diagram of the key remediation measures that need to be undertaken.

Enhancing monitoring and recording systems

Proper monitoring is the first crucial step in addressing this dire condition affecting the city’s health and well-being. The government of Bangladesh initiated the Clean Air and Sustainable Environment (CASE) project to monitor air pollution across the country. Under this project, to provide real-time air quality information, the DoE installed 16 Continuous Air Quality Monitoring Stations (CAMS) in eleven cities: Dhaka has 4 stations, Chattagram has 2, and Gazipur, Narayangaj, Narsingdi, Khulna, Barishal, Rajshahi, Sylhet, Rangpur, Cumilla, and Mymensingh, each has one. All of these CAMS record concentrations of PM2.5, SO2, NO2, O3, and CO in the surrounding air of the station location based on which daily Air Quality Index (AQI) data is provided. However, 16 stations are insufficient to assess national air quality, and four stations alone cannot accurately represent Dhaka’s air quality. If there are no monitoring stations installed in areas like industrial and other active zones, how can we measure the quality of air for those areas? How can meaningful management strategies be developed without detailed spatial air quality data for all those zones?

Bangladesh launched the National Air Quality Management Plan (2024–2030) (NAQMP), developed by the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change and the Department of Environment. The primary goal of the NAQMP is to meet the interim target for annual PM2.5 set by the World Health Organization (WHO) while meeting the targets outlined in the national air quality standards: (1) reducing PM2.5 concentration in the air of the entire country to 15µg/m³ and in Dhaka’s air to 30µg/m³ by 2030, and (2) gradually increasing Good and Moderate AQI days annually. Focusing on meeting those targets, a national committee on air pollution control was formed to implement Air Pollution Control Rules (2022) and coordinate with relevant agencies on specific interventions to comply with the new rules. However, this management plan has not been effective due to several resource constraints and limitations. A critical gap in the NAQMP is that it provides a set of suggestions for different entities polluting the air without setting up strict obligations for them. Another weakness is the absence of regulations in the NAQMP to control toxic industrial emissions.

Disease and pollution correlation

To identify the health impacts of air pollution, it is essential to develop a comprehensive locational database of respiratory diseases. Continuous monitoring of patients’ respiratory health with their locational information can be collected throughout the year. Once the database is created, it can be correlated with pollution data to understand how people are affected by air pollution and at what level, according to specific areas.

Issuing air pollution forecasts

Another important measure is to provide 2/3 days of air pollution forecast information so people can take cautionary measures in advance. Preparing this forecast model also requires intensive spatial data, as mentioned before.

Movement of transboundary air pollution. On 28 January 2025, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on the Aqua and Terra satellites captured this true-color image of dust drifting across the Gangetic Plain, stretching over India and Bangladesh. Image by NASA, 2025. SOURCE: BENGAL INSTITUTE

Controlling industrial emissions

Upgrading factory technologies and shifting to clean energy utilization in factories need to be encouraged through tax exemptions. In addition, industries should install indoor air purification systems for the health benefits of the people working there. Since brick kilns significantly worsen Dhaka’s air quality, particularly in winter, alternative locations for these factories should be explored. If relocation is not feasible, improved production methods, such as the Zigzag 2.0 technology proposed by ICDDR,B, must be adopted.

Regulating vehicular emissions and promoting sustainable transportation

Investing in low-emission public transportation infrastructure, such as buses, trams, and metro systems, can substantially reduce emissions by decreasing dependence on private vehicles. This shift will also reduce travel times, minimizing residents’ exposure to traffic-related pollution. Additional measures, such as limiting vehicle speeds, designating parking zones, banning vehicles that emit black smoke, restricting heavy-duty vehicles during the daytime, phasing out expired vehicles or upgrading them with particulate matter reduction devices, implementing stringent regulations for diesel-powered vehicles, and promoting environmentally friendly transportation options, can further curb air pollution from traffic. Improving current motor vehicle exhaust technologies to ensure more efficient combustion will also contribute to reducing emissions. In addition, Dhaka’s footpaths need to be more pedestrian-friendly to encourage people to walk short distances. In summary, Dhaka’s traffic system needs a complete overhaul to create a more sustainable, pedestrian- and eco-friendly urban environment.

Managing construction, road dust, and open sands

The rapid urbanization of Dhaka has led to excessive dust pollution from construction sites and unpaved roads. Implementing mandatory dust control measures—such as covering construction materials, using water sprinklers, and installing dust barriers—can minimize airborne particles. Some studies identified that open sand can travel more than 40 kilometers with wind, and so dust pollution control mechanisms can be developed to reduce particulate pollution from the open sand areas (approximately 17,700 acres) in Dhaka City.

Protecting and expanding urban blue and green infrastructures

Trees and green spaces act as natural air filters, absorbing pollutants and improving air quality. Expanding parks, rooftop gardens, and roadside plantations can mitigate pollution and heat while also providing ecological benefits. Implementing urban forestry projects, particularly in high-traffic and industrial areas, can have a long-term positive impact on air quality. Developing a green tree belt around the city on the riverbanks can be a good option to sink dust and gas pollutants and provide city dwellers with a green ambience.

Implementing strict waste management policies

The burning of solid waste, particularly plastic and organic materials, releases harmful pollutants, including PM, CO, and CO2, into the air. Establishing proper waste segregation, promoting recycling, and enforcing bans on open-air burning should be the top priorities to reduce emissions from waste disposal. Encouraging composting and biogas production can provide eco-friendly solutions and generate alternative income sources.

Improving indoor air quality

Numerous studies have shown that indoor air quality can be just as poor as outdoor air quality. Polluted air from outside can easily infiltrate homes, exposing residents to the same harmful contaminants. Even in air-conditioned rooms, individuals are not immune to toxic air, as air conditioners primarily cool the air but do not filter out pollutants. Installing air purifiers in homes, schools, and workplaces can improve indoor air quality. Additionally, maintaining indoor plants such as aloe vera and spider plants can naturally improve air quality. Promoting cleaner cooking alternatives, such as LPG, electric stoves, or improved biomass stoves, can reduce household air pollution.

Authors: Sanjoy Roy (Coordinator, Geographic Research Unit, Bengal Institute); A K M Tariful Islam Khan (Senior Manager, Development and Communications, ICDDR,B); Dr. Md. Mahbubur Rahman (Project Coordinator, Environmental Health and WASH, HSPSD, ICDDR,B); Nusrat Sumaiya (Director, Research and Design, Bengal Institute); Arfar Razi (Coordinator, Academic Program, Bengal Institute); Israt Jahan Ria (Research Associate, Bengal Institute); Rida Haque (Research and Design Associate, Bengal Institute); Mashiat Iqbal (Research and Design Associate, Bengal Institute); Shaikh Farhana Hossain (Research Associate, Bengal Institute); Atik Ahsan (Senior Programme Manager, Environmental Health and WASH, HSPSD, ICDDR,B); Meftah Uddin Mahmud (Research Investigator, Environmental Health and WASH, HSPSD, ICDDR,B)

Advisors: Dr. Tahmeed Ahmed (Executive Director, ICDDR,B); Kazi Khaleed Ashraf (Director General, Bengal Institute)