March 17, 2025

THIMPHU – Nine-year-old Jigme Palden walks into a retail shop in Changbangdu, Thimphu, and buys a can of beer without any qualms. The shopkeeper neither asks his age nor hesitates to sell him alcohol, despite strict regulations that prohibit liquor sales to individuals under 18.

This scene is far too common across Bhutan, where minors like Jigme Palden openly purchase and consume alcohol. While the law is clear—selling alcohol to children is illegal—lax enforcement and a lack of accountability have made alcohol easily accessible to young people, including underage children.

“No one questions when minors buy alcohol because it is available everywhere,” says Sangay Choden, a concerned parent.

Growing health crisis

The consequences of widespread alcohol consumption are dire. Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) cases surged from 2,393 in 2021 to 2,625 in 2023, according to the Annual Health Bulletin 2024. While there was a slight decrease in 2022, ALD cases saw an overall increase last year.

Deaths from alcohol-related diseases remain consistently high, with 146 deaths recorded in 2022 and 129 in 2023. The highest fatalities were reported in 2020 and 2021, with 169 and 176 deaths, respectively.

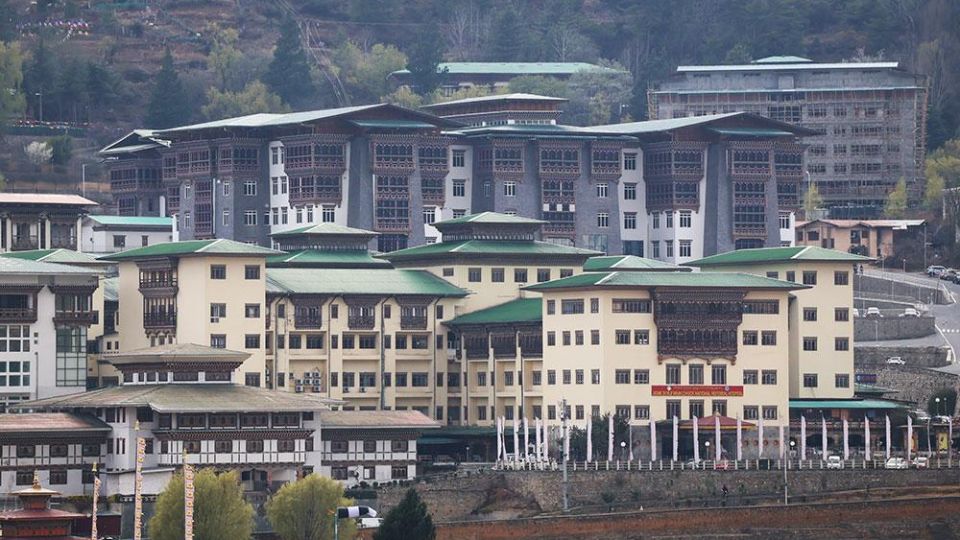

Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital (JDWNRH) reported 2,701 cases of ALD in the past five years alone—with 536 cases in 2020, 454 in 2021, 506 in 2022, 599 in 2023, and 606 in 2024.

Out of 2,701 ALD referral cases referred to the hospital, a total of 371 people died at JDWNRH in the last five years.

“The cost of treating alcohol-related diseases is enormous,” says a health official. “Excessive alcohol use increases the risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), contributes to the spread of HIV through risky behaviour, and worsens conditions like tuberculosis by weakening the immune system.”

According to health experts, individuals who continue to receive treatment through health centres result in significant costs for both the government and individuals.

Dr. G. P. Dhakal of JDWNRH said that most patients visit hospitals only when their liver is severely damaged or when alcohol dependence reaches a critical stage. “No amount of alcohol is safe for your health. If you find yourself at risk of hazardous drinking, visit a hospital for treatment and can seek counseling,” he said.

Besides other expenses, the liver transplant, alone cost between Nu. 2 to 3 million.

Alcohol consumption trends

A health survey data shows Lhuentse has the highest alcohol consumption rate, followed by Pemagatshel and Punakha. Trashigang leads in home brewing, with Mongar, Lhuentse, and Zhemgang following closely behind.

The two most common sources of alcohol in Bhutan are homebrewed beverages and industrially distilled liquor. Beer is the most consumed alcoholic drink in both urban and rural areas, while ara and singchang, both homebrewed, are prevalent in rural communities.

A health survey found that wealthier Bhutanese tend to consume wine and spirits, whereas lower-income groups predominantly consume homebrewed alcohol, which is often more harmful due to high ethanol content and lack of regulation.

While globally, 23.5 percent of 15- to 19-year-olds are current drinkers, in Bhutan, the highest percentage of alcohol consumers fall within the 25 to 39-year-old age group. Students and retirees also contribute significantly to the country’s drinking statistics.

The World Health Organization (WHO) also reports that Bhutan has the highest wine distribution in the Southeast Asia region.

Social costs: Accidents, crime, and domestic violence

Alcohol is a leading cause of road accidents in Bhutan. The Royal Bhutan Police (RBP) and the Bhutan Construction and Transport Authority (BCTA) report that human error is the primary factor in most accidents, with drunk driving being the leading cause.

Between 2020 and 2024, Bhutan recorded 4,516 road accidents, 791 of which were alcohol-related. The numbers have steadily increased, from 123 cases in 2020, 120 in 2021, 128 in 2022, 195 in 2023, to 225 cases in 2024.

Over the past five years, alcohol-related accidents have claimed 30 lives. This means, on average, six people have died each year due to alcohol-related accidents.

Alcohol is also a significant contributor to crime. Police records show that 1,527 domestic violence cases linked to alcohol were reported between 2020 and 2024. In 2020, 182 cases of domestic violence were reported, 297 in 2021, 407 in 2022, 325 in 2023, and 316 in 2024.

Police reports also indicate an increasing trend in crime committed by adolescents, mostly under the influence of alcohol.

According to statistics of BCTA, a total of 4,194 people were caught driving under the influence of alcohol in 2023, up from 1,334 in 2022. The number dropped slightly to 2,949 last year. However, it remains a major concern.

Alcohol business

There are 9,717 active alcohol-selling establishments in the country—roughly one for every 75 people.

The previous government lifted the restriction on issuing bar licenses and raised the sales tax on alcohol by 100 percent to curb the black market and reduce alcohol availability. However, experts argue that an increase in taxation has not made much changes to consumption and access.

“Increasing taxes on alcohol hasn’t reduced the consumption of alcohol,” says a health official. “Imports and production of alcohol must be reduced drastically, or stronger regulations must be implemented.”

Experts also warn that alcohol advertising goes unchecked, with promotional activities occurring even at public events and festivals. Drinking is common at social gatherings, archery tournaments, and religious events.

“We need alcohol-free zones and stricter law enforcement,” says Tshewang Tenzin, executive director of Chithuen Phendey Association (CPA), a civil society organisation advocating for substance abuse prevention. “Alcohol is the biggest killer in Bhutan, yet it is not treated as a national emergency.”

Another growing concern is the lack of awareness among people in remote areas regarding the ethanol content in alcohol. Locally brewed alcohol carries high health risks, yet no regulation or monitoring exists.

Officials from the Ministry of Health agree that studies show a strong link between access to alcohol and consumption.

Need for urgent action

Despite mounting evidence of alcohol’s devastating impact, there is little regulatory action.

“Drugs claim only one or two lives a year, but enforcement against drug use is strict,” says Tshewang Tenzin. “Alcohol, on the other hand, kills hundreds annually, yet remains widely accepted.”

Efforts to reduce consumption are often met with cultural resistance. “We say drinking is part of our culture, but at what cost?” asks Tshewang Tenzin.

Sending a person with alcohol dependence to rehab costs between Nu 8,800 and Nu 20,000 per month at CPA facilities, while treatment in India costs more than NU 18,000 per month.

Pema Wangda, who advocates for alcohol regulation, said that besides regulations, monitoring the sale of alcohol is necessary. “Collaboration and consultation at the grassroots level are needed to address the alcohol availability, where everyone can work together to save each other’s lives,” he says.

He adds that individuals with alcohol dependence burden their families and spend a large portion of their income on liquor, pushing them deeper into poverty.

Experts call for a multi-pronged approach—stricter enforcement of age restrictions, tighter control on alcohol sales, education campaigns, and the establishment of alcohol-free zones.

Meanwhile, the WHO’s Global Alcohol Action Plan 2022–2030 and SAFER initiative provide evidence-based strategies to curb alcohol abuse. Bhutanese authorities could adopt similar frameworks to mitigate the crisis.

Currently, the Ministry of Health, along with The Pema Secretariat, offers essential services such as counseling, detox, and rehabilitation to support individuals in addressing and correcting their behaviours.