January 5, 2022

Toxic nationalism manifests online via ‘gukppong’ YouTube channels

In 2015, when Tottenham Hotspur of the English Premier League acquired forward Son Heung-min — arguably the best soccer player Korea has ever produced — a curious fad emerged among Korean soccer fans.

Whenever Son pulled off a remarkable performance, they would flood online comment sections with the word “Jumo!”

It was meant as a compliment. The Korean word refers to the now-defunct profession of a female barkeep. By saying jumo, the fans were saying they wanted more drinks, because they were “drunk” with the pride that Son had given them.

It was a cute and seemingly-innocent fad at that time, but the nationalism that has manifested online recently often takes on a much uglier form.

On YouTube, exaggerated headlines and thumbnail images designed to incite blind nationalism have flourished, giving rise to a new genre of content called “gukppong.”

Rise of gukppong

The term is a combination of “guk,” meaning nation, and “ppong,” a term for methamphetamine believed to have derived from philopon, a brand name widely substituted in East Asian countries. By combining the two words, it likens indulgence in nationalism to being high on drugs.

In earlier years, the term was used mostly as a joke to ridicule members of the media who overly focused on Korean products’ or peoples’ success overseas.

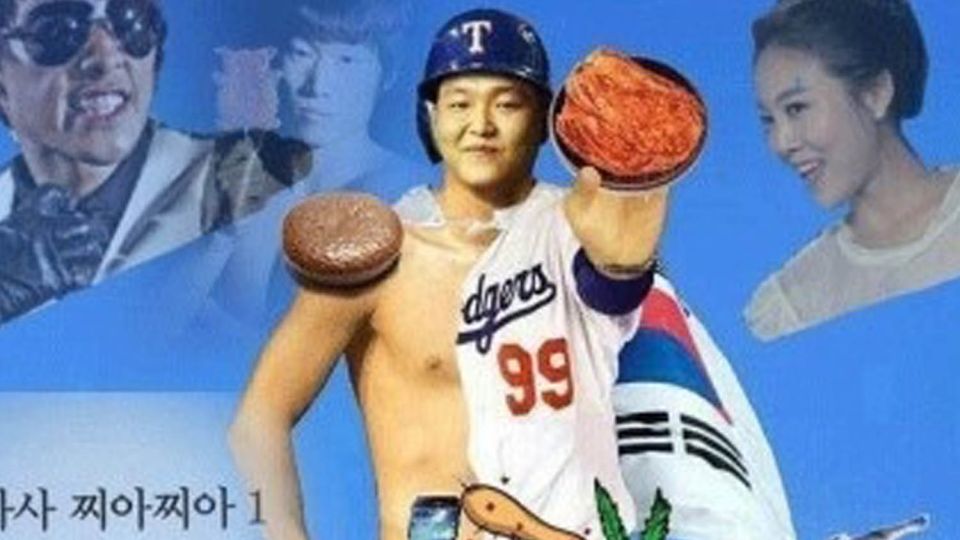

This parady image compiles all things that Koreans are supposedly proud of, including Psy’s face, Ryu Hyun-jin‘s jersey, Choo Shin-soo’s helmet, Dokdo, singer Rain and kimchi.

For example, when Korea’s Park Ji-sung was playing for EPL’s Manchester United from 2005 to 2012, some Korean reporters would ask anyone from Europe or the US their opinion of Park regardless of the context, hoping to hear some words of praise. When the person said he or she was a fan, that would be the headline.

To be sure, Koreans in general are mindful of what other countries think of their country or compatriots.

“We started industrialization late and have always been followers of Westerners, which has led to a deeply-rooted (inferiority) complex against them. This leads Koreans to be sensitive toward what they think, yearning for their approval,” pop culture critic Ha Jae-geun wrote in his column about gukppong.

This collective longing for validation is one of the factors behind the success of foreigner-run, Korea-focused YouTube channels such as “Korean Englishman.”

Gukppong takes this to the extreme. The topic of gukppong videos on YouTube vary from culture, politics, and even the military, but they tend to share a clear commonality. Gukppong video titles emphasize how Korea or Koreans are “ahead” of their country’s rivals.

Japan, with its history of bad blood with Korea, often falls victim to such comparisons. China is also another target.

On one such channel, a video is titled “The final results: Chinese military vs. Korean military. Why China could never win.” It concludes that while it is impossible for Korea to defeat China in war, it would also be impossible for China to conquer Korea. The narrator describes the Chinese military as “a pig that is big but has a lot of fat,” while describing Korea’s military as small but “muscle-bound” and “a professional fighter with all the skills.”

Thumbnail images of YouTube videos with “gukppong” content. These particular videos are titled, (top) “Soju fiercely growing (in popularity) overseas, only Koreans don‘t know about it: Korea’s soju selling rapidly as a top-quality liquor,” (bottom) “We fear Korea now. There is no way to keep up with Korea: Japan‘s top economic expert spills the beans on the curren situation of Korea and Japan” (YouTube)

Ggukppong sells, but at a price

Validity of the claims aside, gukppong sells big time.

The Korea vs. China video, which has virtually no fact-based analysis about a potential Sino-Korean conflict, has garnered 3.7 million views and 48,000 likes. It ends with, “It is unlikely that China, which has its hands full with Taiwan, will dare start a war with Korea. All praise Korea!”

While the aforementioned video’s channel does not disclose its number of subscribers, its videos have accumulated well over 177 million views in total as of December 2021, in little under two years since it started operation in February of 2020.

It is worth noting that the comment sections of this channel are almost unanimous in spirit, impassioned with nationalistic pride about a fictional war and an imaginary show of force.

Some videos go beyond subjective analysis based on scant evidence, and downright falsify facts on the topic. A video titled “Prophesies about Korea becoming a superpower coming to reality,” claims that it is “perfectly viable” for Korea to colonize Japan and annex Vietnam. It also claims that well-known investor Jim Rogers said Korea will soon surpass China, Japan and the rest of the Western world to rival the US.

Needless to say, Rogers never said such thing. One could speculate that the creators of this video took Rogers’ remarks about how a united Korea would be “the most interesting place in the world,” and blew it out of proportion to a near-comical degree.

Thumbnail image of a YouTube video with “gukppong” content. This particular video is titled, “The top 5 Korean weapons China is most scared of: Invading Korea? Not a chance.” (YouTube)

But while gukppong videos might often seem ridiculous, they start chains of false information that, when circulated enough, become akin to established facts.

One such example is a decadeslong notion shared by some people that Japan had changed the spelling of the country from “Corea” to “Korea” during its 1910-1945 colonization of the peninsula, because Japan could not tolerate its colony being mentioned alphabetically before it. The rumor was so widespread that even JTBC’s Son Suk-hee — one of the most respected journalists in the country –was said to have believed it at one point. This was eventually debunked in a video with photographic proof that both Korea and Corea were used in the late 19th century — well before Japanese colonization — in documents and postage stamps.

While patriotism is a value that is touted in most parts of the world, it could easily become toxic, experts warn.

Professor Lee Jong-hyuk of Kwangwoon University’s School of Media & Communication said there are currently two extreme forms of nationalism rampant in the country. One is ggukppong, and the other is “gukka,” referring to a practice of denigrating everything related to Korea. This includes the term “Hell Joseon,” which became popular among young Koreans around 2015, likening the country to a hell on earth.

“Gukppong is an imperfect form of pride– one that is not mature. It is patriotism that is solely based on extreme idealistic values.” Lee said in his online lecture. “If we only have gukppong and gukka, the state would not be able to sustain itself. It’s because society will be overrun by conflict and hostility.”

Poet Mun Gye-bong says what gukppong content provides is not pride, but an illusion.

“Being biased for one’s country for a momentary illusion would result in one isolating oneself in all forms of relationships,” he wrote in an article.

Gukppong may have started out innocently, as cheering for a compatriot playing in one of the top soccer leagues in the world. But over time, it seems to have grown into something far less pleasant.

“Being proud of one’s country is fine. But indulging in gukppong content based on very thin evidence, and being deluded into thinking ‘Korea is the best at everything, all the time’ is something to be careful about,” said cultural critic Ha.