May 27, 2025

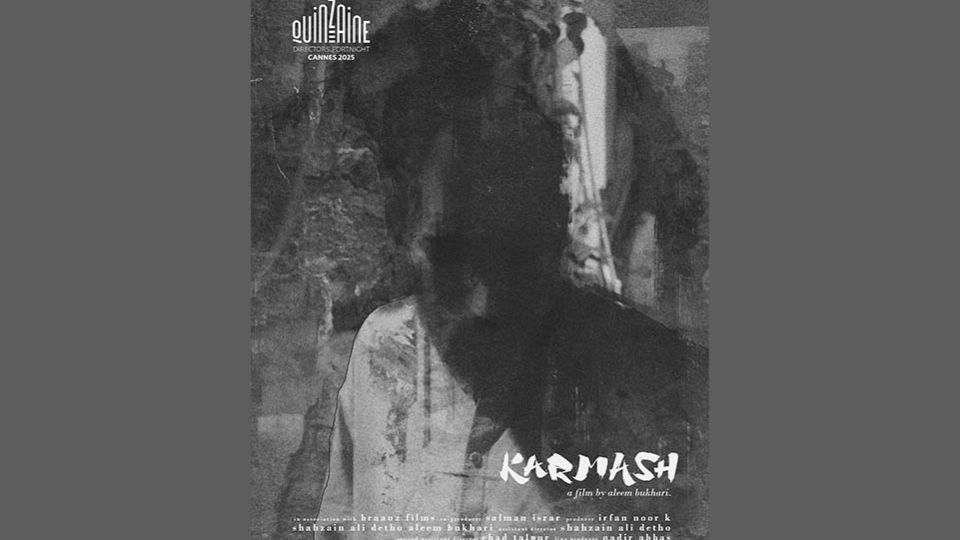

ISLAMABAD – Aleem Bukhari’s new short film Karmash has quietly made history. The experimental horror piece has been selected for screening at the Cannes’ Directors’ Fortnight, an independent sidebar at the Cannes Film Festival. The director says it is the first-ever Pakistani short film to be featured in this section in the festival’s 56-year history.

The film had its world premiere at the festival on May 22. That’s no small feat. Only three Pakistani films in total have ever made it to this prestigious programme, with Karmash being the third.

What’s even more compelling is how it got there.

No formal film school. No production house. No corporate backing. Just six friends, a tiny budget, and a shared vision. The film was produced entirely under the independent label Sleepbyte Films, and it represents a major moment for homegrown cinema from Pakistan.

The short film explores a surreal and unsettling narrative about the last heir of the Karmash tribe, wandering through the ruins of memory, tradition, and identity, all set against the slow decay of the city around him. There’s an eerie, lingering tension built through striking sound design and a standout performance by Irfan Noor K, whose physicality has been likened to the Japanese Butoh dance, bringing a 1960s-style Japanese cinematic intensity to the screen.

Bukhari, who was behind Sapola in 2018 and Anaari Science in 2024, says Karmash reflects his continued interest in strange, out-of-the-box storytelling. Speaking to Images about what inspired him to work in horror, a genre rarely explored in Pakistani indie film, he explained, “Yes, exploring horror here is rare, and what we do see is usually haunted houses and ghost stories.

“But I personally like the genre because it does more than just scaring the audience. It gets under the skin. Horror can be melancholic, it can be sombre , and that lets it target a diverse set of emotions. Karmash uses horror the same way you’d approach a character study.”

The title ‘Karmash’, the filmmaker explains, translates to “one who follows his legacy” or “one who does his duty.”

“It felt like the right word for this film, someone who is the last heir of his tribe and remains deeply connected to his past and heritage. That was really the heart of the concept: I wanted to explore what happens when a person is trying to hold on to their culture and ancestry in a world where authoritarianism is real and cultural erasure is very present.”

This central idea is what lends Karmash its emotional weight. The film doesn’t show the oppressor, it focuses entirely on the oppressed and how that trauma unfolds internally. It’s a conscious decision to keep the spotlight on the psychological unraveling that occurs when someone refuses to let go of the past.

“It’s a universal theme,” Bukhari adds. “There are so many marginalised cultures across the world that are being persecuted. Their identities are being stripped away. And for us, where we’re from, we’re witnessing it in real time. So, in that sense, it’s deeply personal too.”

A quote by Friedrich Nietzsche comes to mind — “And those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.” Bukhari nods at this line when describing how his character appears — someone who, by societal standards, looks unhinged, but is actually holding on to a past that no one else sees. When asked whether Karmash was always meant to be a short film or if it was a test run for something larger, Bukhari was clear, “It was always going to be a short film. I wanted to try telling a very small story with just a few scenes and a tight narrative. We made it with a near-zero budget, that’s all we had. But I also hope it encourages younger creatives. You don’t need a studio or a big budget. The biggest barrier is this industry gatekeeping, which discourages people from even trying. So, for me, more than the final output, the journey of making Karmash is what I find most inspiring.”

So how did Karmash end up at Cannes?

“Honestly, we never imagined this. We submitted to a bunch of festivals, and Cannes was one of them. No expectations. That’s why it felt so overwhelming when it got in. I feel honoured. Cannes treats its artists with a lot of respect. This is just the beginning. I do hope to move on to bigger projects now. And with better funding, because those projects will definitely need it.”

Bukhari offers a stark commentary on the persecution of minorities in Karmash. The protagonist’s self-identification as the last of his tribe, combined with his social ostracism, makes this theme apparent. His actions, seen as grotesque by societal standards, are portrayed as necessary for survival, intensifying the critique while adding shock value. Notably, the horror emerges more from sound than image. In many ways, Karmash isn’t just a film, it’s a statement. It’s a reminder that powerful stories don’t need polish or permission. They need urgency. They need voice. And they need space to be heard.

This one found that space at Cannes.