September 11, 2025

PHNOM PENH – An alarming investigation by Cambodia’s Local Guides community has uncovered systematic digital harassment campaigns on Google Maps, revealing hundreds of offensive and fake locations targeting the country’s cultural symbols, tourist landmarks and border territories.

This digital assault is particularly prominent along the Thai-Cambodian border, with a staggering 60 per cent of violations occurring in border provinces, and overwhelming use of Thai language in violation titles.

According to the Google Maps Location Violations Investigation Report 2025, volunteers documented 568 problematic listings across 18 provinces, with 341 still active.

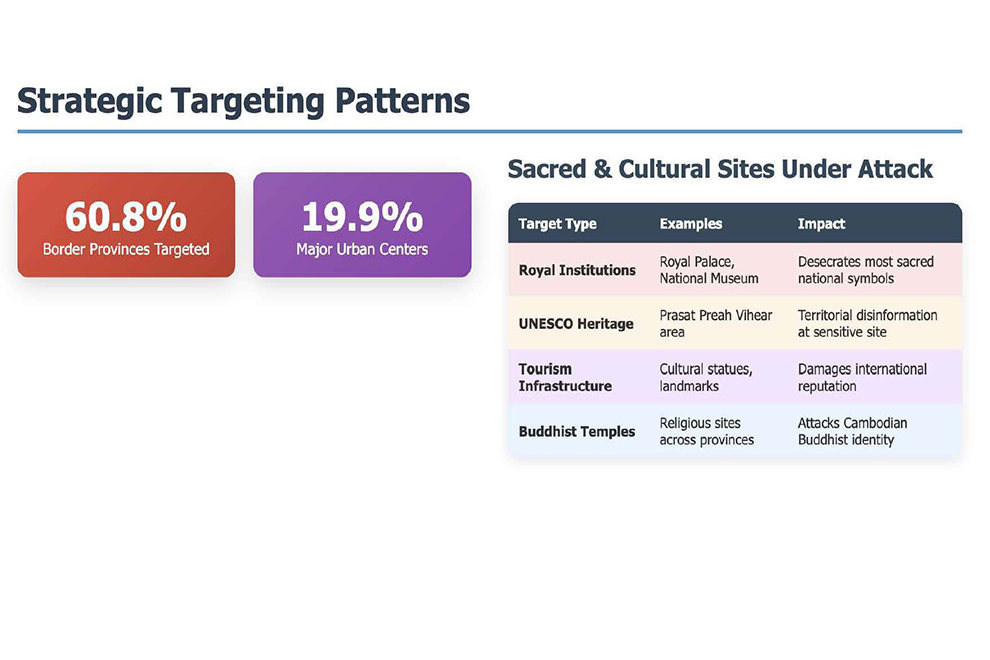

Many of these locations carried insulting names in Thai script — accounting for 95 per cent of the violations — and were deliberately pinned to sacred sites such as the Royal Palace, the National Museum and UNESCO World Heritage site the Preah Vihear Temple.

“The use of Google Maps, a tool meant to help communities, has been weaponised,” Moses Ngeth, a lead investigator, told The Post.

“Our analysis shows how contributors exploited weaknesses in Google’s verification system, pushing harassment and disinformation into the digital landscape of Cambodia,” he added.

The community observed new locations appearing with Thai language titles on Cambodian territory, containing offensive content or targeting local figures, said the report.

“The timing and patterns suggested these were not random incidents but coordinated digital activities linked to the physical border conflict,” it said.

Chy Sophat, lead researcher at Cambodia Local Guides, presents the Reclaiming Our Digital Space report on Google Maps abuses, Sept. 6, 2025. PHOTO: SUPPLIED/THE PHNOM PENH POST

Offensive campaigns target national identity

Among the most disturbing findings were fake place names pinned directly on Cambodia’s most respected landmarks.

The National Museum was labelled with derogatory titles aimed at political figures, while the Royal Palace — the most sacred institution of the Cambodian monarchy — was desecrated with obscene references.

“This is not random vandalism,” stressed Chy Sophat, another lead investigator of the volunteer Local Guides group.

“It is systematic. Locations were deliberately chosen — our cultural icons, our sacred sites and our border communities. These attacks aim to damage Cambodia’s tourism reputation and national dignity,” he noted.

Of these active violations, a staggering 93 per cent were found to be harassment-related, where fake locations were created with offensive or politically charged names.

The investigation further documented false territorial claims near the Preah Vihear temple, echoing decades of border disputes.

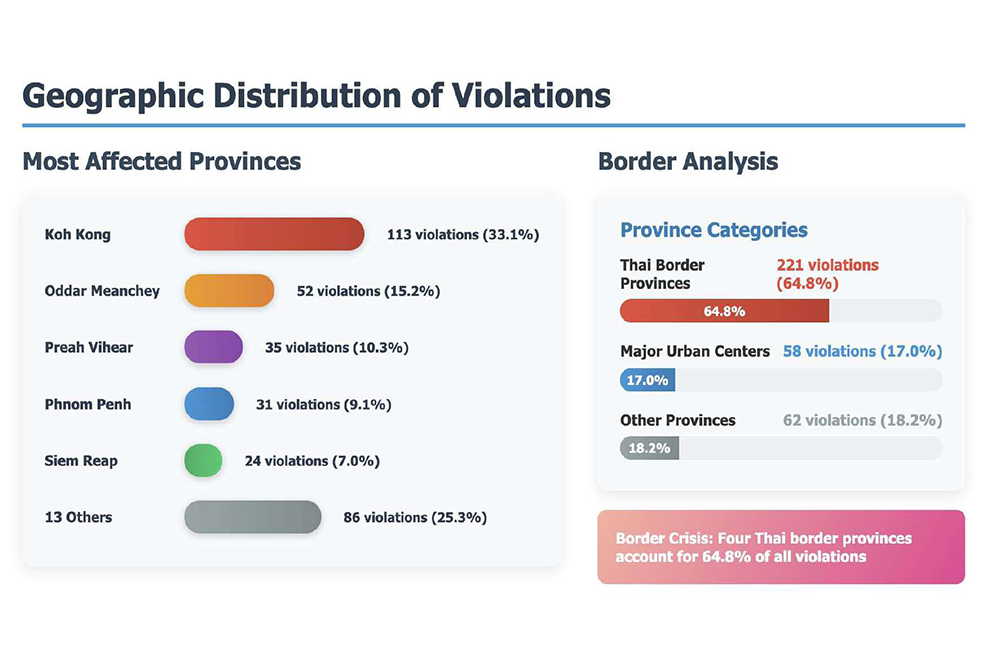

Offensive content also targeted emerging infrastructure in border provinces, particularly Koh Kong, Oddar Meanchey, Preah Vihear and Banteay Meanchey, which together accounted for nearly 65 per cent of all violations.

The Cambodian Royal Palace, UNESCO World Heritage sites and other prominent national symbols have all been targeted in a bid to undermine Cambodia’s cultural pride and international reputation.

“The scale and scope of this harassment are unprecedented,” said Ngeth.

“What we’re witnessing is not just random vandalism, but a methodical, well-organised attempt to manipulate digital information about Cambodia,” he added.

The analysis suggested that the use of Thai script in the location titles and the way they’re written, the historical review locations’ geographic information, and the high-level contributors’ involvement are likely to indicate that the source is Thai.

Offensive content targeted new infrastructure in border provinces, with Koh Kong, Oddar Meanchey, Preah Vihear, and Banteay Meanchey making up nearly 65 per cent of all violations. PHOTO: SUPPLIED/THE PHNOM PENH POST

Technical tools and community verification

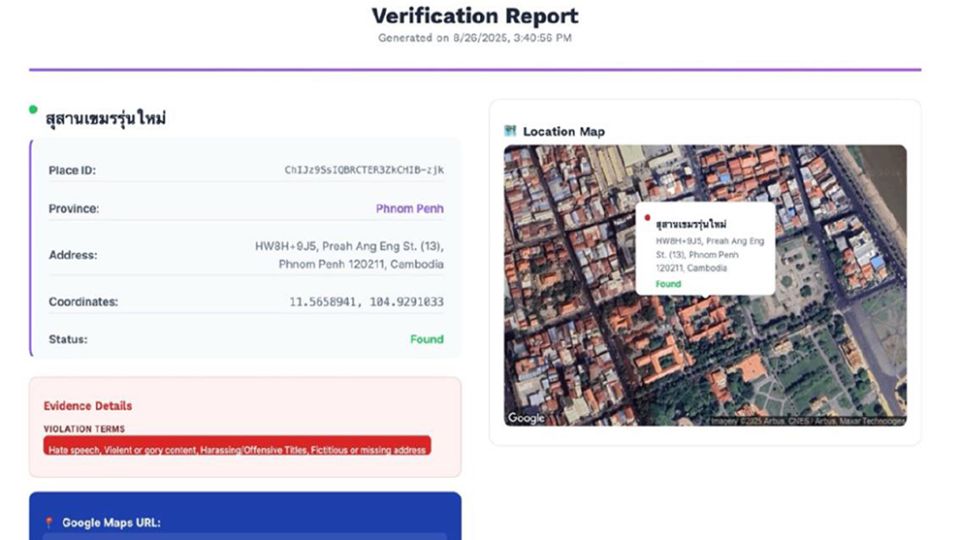

To gather evidence, investigators built a custom tool using Google’s official Places API and Maps JavaScript API.

“The tool allowed us to systematically archive fake locations by storing unique Place IDs and related data,” explained Ngeth.

“This creates a permanent record — even if the malicious location is later removed,” he added.

Ngeth said they utilised the official Google API and relied on their trained community to manually verify, check and categorise locations.

They added that community members who speak Thai and understand the culture were able to recognise hidden hate speech in the language.

Ensuring accuracy was critical.

“We combined technology with human verification,” said Sophat.

“Community members fluent in Thai helped us identify hidden hate speech and coded language that automated systems cannot detect,” he noted.

A significant portion of the investigation focuses on the inadequacies of Google’s current safety and verification systems.

According to Ngeth and Sophat, the platform’s reliance on community reporting and its automated filters — while valuable — have proven ineffective in addressing the full scale of the problem.

Despite these efforts, only 40 percent of reported violations have been removed by Google, leaving a majority still visible.

The investigation underscores a broader issue of digital sovereignty in Southeast Asia.

As technology continues to bridge borders, the abuse of platforms like Google Maps becomes an increasing point of contention for countries trying to protect their cultural and digital landscapes.

“The current situation exemplifies a form of digital warfare where external forces manipulate online platforms to attack local sovereignty,” Sophat told The Post.

Both investigators agree that addressing this issue requires a multi-faceted approach, involving not just local community reporting but also government intervention and, crucially, dedicated support from Google itself.

They called on the Cambodian government to establish a task force to monitor Google Maps and collaborate with the global tech giant to improve detection mechanisms and speed up removal of harmful content.

The use of Thai script in location titles, along with geographic data from historical reviews and involvement of high-level contributors, points to Thailand as the likely source of the violations. PHOTO: SUPPLIED/THE PHNOM PENH POST

Impact on tourism and reputation

The investigation warns of long-term consequences if unchecked. Fake tourist attractions and manipulated reviews could mislead international visitors, while offensive content attached to cultural landmarks tarnishes Cambodia’s image abroad.

“These violations do not just harass individuals — they undermine Cambodia’s economic interests,” Ngeth noted.

“Our tourism industry depends on authenticity and trust. If digital disinformation continues, it risks eroding both,” he added.

He believed the impact of this digital harassment is clear: Cambodia’s tourism industry, which heavily relies on its cultural and historical landmarks, is at risk.

Fake tourist attractions and misleading reviews are contributing to a decline in trust, which could discourage international visitors from traveling to the country.

“Tourists depend on accurate information, and when they encounter fake locations or offensive content, it disrupts their plans and harms Cambodia’s reputation,” Sophat added.

The platform’s reliance on community reporting and speed of publication makes it vulnerable to exploitation by malicious actors.

60.8 per cent of violations targeted Cambodia’s border provinces and 19.9 per cent major urban centres, with sacred and cultural sites—including the Royal Palace, Prasat Preah Vihear, and Buddhist temples—coming under coordinated digital attacks. PHOTO: SUPPLIED/THE PHNOM PENH POST

Weaknesses in Google’s safeguards

The report identifies structural flaws in Google’s system, particularly its reliance on higher-level contributors whose edits are approved more quickly.

“That trust system is being manipulated,” said Ngeth.

“High-level accounts can push through malicious edits faster than they can be detected,” he warned.

Google’s automated filters, meanwhile, fail to recognise offensive Thai-language content before publication.

“This is why 95 per cent of the violations slipped through,” Sophat explained. “Google’s detection system is blind to cross-language harassment.”

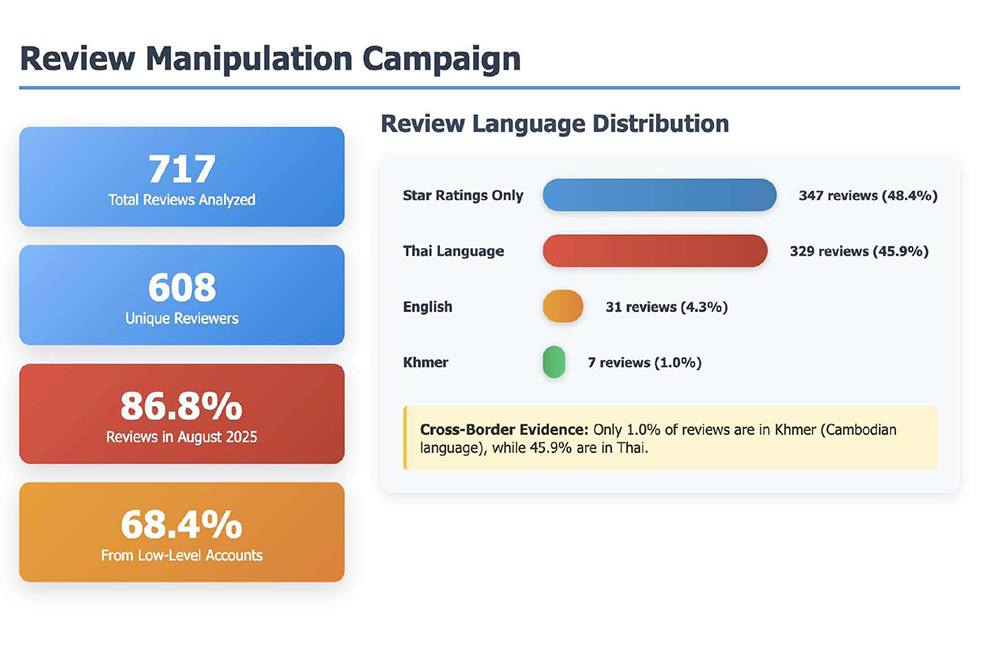

Data shows 717 reviews were analysed, with 86.8 per cent posted in August 2025. Nearly half of the reviews were written in Thai, while only one per cent were in Khmer — evidence of systematic cross-border manipulation. PHOTO: SUPPLIED/THE PHNOM PENH POST

Calls for action

The Local Guides community is urging stronger intervention. They recommend:

- Government action: establishing a technical working group, particularly within the Ministry of Tourism, to work directly with Google.

- Community training: expanding reporting skills among volunteers to ensure violations are properly documented.

- Corporate accountability: pressing Google to assign dedicated support for Cambodia and invest in regional moderation.

“Our community has done its part,” Ngeth said. “It is now up to the Cambodian government to engage Google directly and demand urgent solutions.”

“This is about digital sovereignty. Cambodia must protect its cultural identity online as much as it does offline,” added Sophat.

The report concludes that if systematic abuse continues, Cambodia should consider developing localised map technologies to safeguard its digital landscape.