September 25, 2025

DHAKA – Walk through Dhaka at any time—depending on the neighbourhood, there is always something remarkable to witness. People gather wherever they can find shared space—on traffic islands, building steps, and sidewalk corners. They transform street nodes into makeshift community centres, and tea stalls into neighbourhood gatherings.

City authorities may ignore public space, but residents do not. People create public life wherever they can. Street vendors, food vendors, and tea stalls—everywhere, people are reclaiming their spaces, transforming them into street markets and food courts. This is not chaos—it is what urbanist Jane Jacobs recognised as the ‘sidewalk ballet’, the spontaneous coordination that makes cities work.

This is not urban disorder, though that is how it is often perceived. These informal space-making practices are evidence of our most fundamental urban need, one that formal planning has somehow forgotten to address.

We spend billions on expressways and megaprojects that look impressive in photographs, while overlooking something far more valuable: public spaces. They are the true capital of this capital city, yet we treat them as if they do not matter at all—or perhaps we have forgotten that they ever could.

Who is to blame for this forgetting? Is it the pressure of rapid building, or have we actually lost our way with being public?

How the ability to see value is lost

We do not just lack public spaces—we have forgotten why they matter. In a recent workshop I conducted with the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements, participants were asked about their favourite public spaces. Almost everyone described a gated and heavily policed park. When I asked if sidewalks count as public space—if walkable streets are as basic a right as food, education, or healthcare—most participants looked confused.

This shows how our spatial imagination has been shaped. Pointing to “an old classist perspective,” Professor Kazi Khaleed Ashraf notes that many middle-class residents avoid anything public, associating it with chaos and disorder. The middle and upper classes, he argues, “generally avoid anything associated with the public, be it people or places.” Many have internalised the idea that public space equals disorder, that safety requires exclusion, and that quality demands control.

The commons should be a welcoming and vibrant place. CONCEPT PLAN BY BENGAL INSTITUTE/PUBLISHED IN THE DAILY STAR

Public space critic Matthew Carmona’s work on contemporary public space identifies this as part of a broader debate between those who see public spaces as “overmanaged” (commodified, homogenised, controlled) and those who see them as “undermanaged” (neglected, poorly designed, insecure). Both perspectives miss what is actually happening. Dhaka’s informal spaces are successful examples of community self-organisation that formal planning consistently fails to understand or adapt to. Consider how the community under Dhaka’s Tejgaon-Nabisco Flyover has autonomously organised socio-economic activities spanning a full kilometre, or how Karail’s 200,000 residents have self-organised utilities and services over four decades.

What the streets already know

Assessing the “publicness” of urban spaces through their physical configuration and animation qualities, our research found something obvious yet overlooked. Even a traffic-dominated street on a service road named Bir Uttam Aminul Haque Sarak in Banani, which scored only 5.5 out of 10 on ‘comfort’ measures, was consistently described by users as “vibrant” and “welcoming.”

People tolerate significant discomfort and poor infrastructure for the sake of good community. When assessing the “experiential qualities” that matter to users—comfort, inclusiveness, vitality, image, and likeability—these informal spaces often scored surprisingly high on animation and social engagement, even when their physical infrastructure failed basic comfort standards. We see a street corner, or even an entire street, transform into a place where strangers can become neighbours.

In contrast, our second study site—the Gulshan-Badda link road, adjacent to Gulshan Lake—preserved natural elements while remaining publicly accessible, and scored 8.6 out of 10 on measures of genuine “publicness,” even though it is primarily a “passing through” zone for office-goers. The difference was not in the amount of policing or control, but in whether the space could accommodate what communities actually needed: opportunities for both passive engagement (sitting, watching, being present) and active engagement (conversation, social interaction, community building).

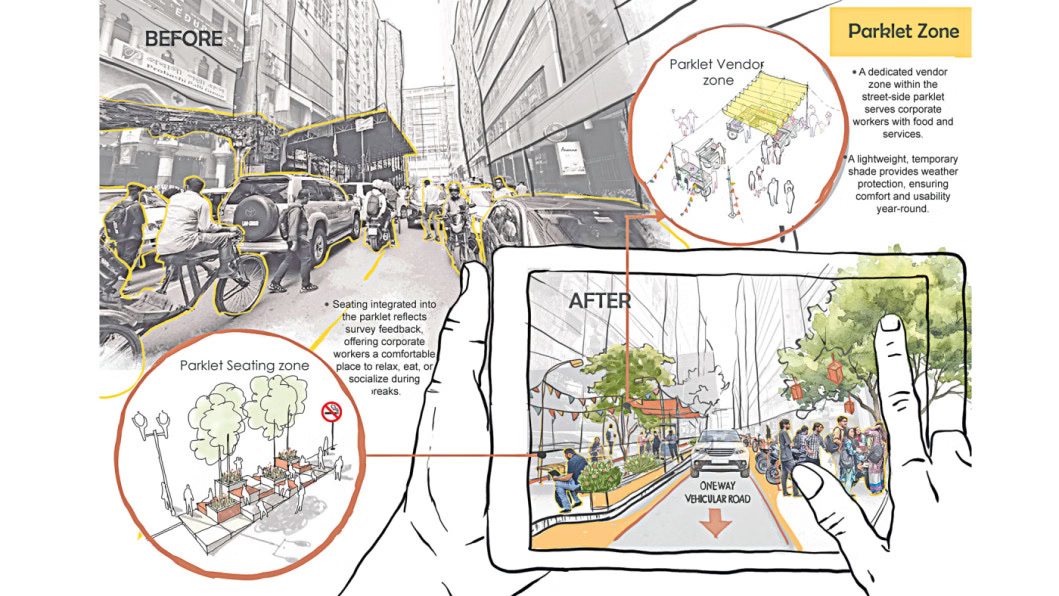

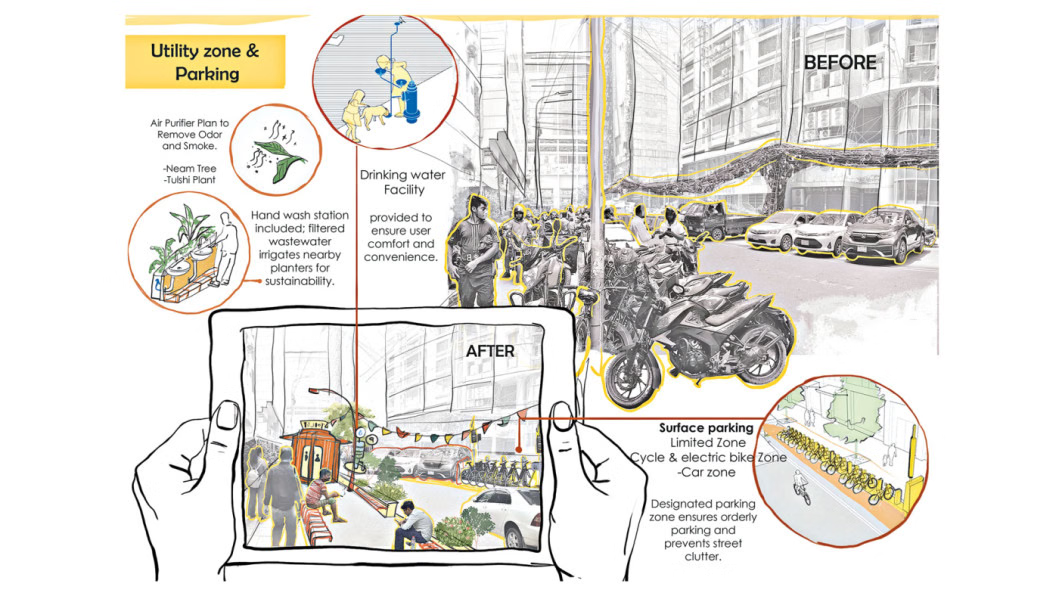

The art of spatial reorganisation: Before and after street transformation. From the workshop “The Making of Publicness”, organised by Bengal Institute, 2025. PHOTO: BENGAL INSTITUTE/THE DAILY STAR

Nobody talks about this anymore

What is troubling is that we discuss community development endlessly but rarely mention its foundation: shared space where communities can actually form.

Sometimes critics dismiss public space advocates, claiming they commit “epistemic violence” by imposing Western models on the local context. This accusation treats imagination itself as suspect, as if envisioning better public spaces automatically means copying the West. But the demand for public space comes from Dhaka’s streets, not Western textbooks. It is emerging organically from our streets, our riverbanks, our terminals, and our lakefronts. When someone challenges a footpath monopoliser (particularly motorbikers on footpaths) with “GB dyUcvZ wK †Zvi ev‡ci?” (“Does this footpath belong to your father?”), they are asserting something essential: certain spaces must remain common because they constitute the very possibility of collective life.

What we lack is not just imagination but political courage. Policymakers focus on piecemeal projects rather than bold decisions for the greater community. Investing in public space does not seem to be considered “sexy”. Can we actually recall any moment when investors were excited about funding a public space, or agencies gave it real attention—except for Sir Patrick Geddes’s advocacy and planning of Dhaka’s Ramna Park in the 1920s? Does our city authority now consider this a capital investment?

Beyond vehicular dominance: Organising streets for people and mobility. From the workshop “The Making of Publicness”, organised by Bengal Institute, 2025. PHOTO: BENGAL INSTITUTE/THE DAILY STAR

The violence of everyday spatial life

The absence of quality public space creates daily violence that we have somehow normalised. Women die from falling construction debris while walking on pavements. People fall through open manholes during rain. Families are electrocuted to death on waterlogged streets when electrical wires fall into floodwater. Students are killed by garbage trucks while crossing roads because there are no safe pedestrian crossings. How many go unreported?

This is not just about accidents. It is about what happens to a society when people cannot safely gather, when children cannot play freely, when the elderly cannot walk peacefully.

Some basic questions reveal our spatial poverty: can you imagine reading a book beside a road in Dhaka, sitting? Can your elderly parents have a peaceful conversation while walking on our pavements, over the constant honking? Where do we take our children to show them the sky, to let them explore nature—even within their minds—in some indoor, fancy establishments? How long can anyone have peace of mind while walking through our streets?

We have created a paradox: those fancy tiles on our sidewalks—made with imported materials that break easily and become slippery—are often less walkable than the street itself. We regulate pedestrian movement instead of traffic movement, when people are naturally fluid and organic, growing spontaneously and moving organically. Cars are the rigid, destructive force that requires control—yet somehow we have reversed this logic entirely.

How we could conceive public space differently

Planning documents should start with public space, not end with it. Instead of treating it as ‘undermanaged’ residual space—what is left after roads, buildings, and utilities are accounted for—or ‘overmanaged’ with active and excessive surveillance systems—what if public space requirements became the foundation around which everything else was organised?

While many assume that Dhaka’s population density makes creating ‘space for the public’ impossible, we should challenge this assumption. We have numerous streets—main roads, service roads, and residential roads—that could be put to use, if not fully, then at least partially. We need more research to identify such roads that could be converted into common spaces—to stroll, walk, explore, and discover.

This could include evening streets (closed to traffic during certain hours), living streets (permanently prioritising pedestrians), and shared streets (removing the separation between vehicular and pedestrian areas). Although Dhaka’s streets are predominantly ‘shared streets’, instead of regularising pedestrian movement, vehicular movement and the use of horns should be policed. Most ambitiously, a connecting city-wide network of public space systems should be introduced to link selected streets, parks, and pavements—from Old Dhaka to Dhanmondi, from Dhanmondi to Mohakhali-Banani-Gulshan, and from Gulshan to Badda-Khilkhet-Uttara.

However, what we lack on the streets is age diversity. It is not always necessary to provide seating on every street, but seating remains an important element. A zone could be purely for passing through, like the Gulshan-Badda link road, while other streets host night gatherings—street food and kebab stalls, for instance—from Mohammadpur’s haleem and kebab evenings on Salimullah Road to Khilgaon’s 1.85-kilometre food street on Shaheed Baki Road, Uttara Sector 3’s Wednesday street vendor markets, and Rampura’s tea shop gatherings around the Bangladesh Television headquarters. We should think of providing more seating where it makes sense. The places that people are continuously reclaiming need to be identified and documented. The first task should be to create an inventory.

The city-wide network could help decentralise the population from Dhaka as well. If bike lanes are incorporated into this network, people could use rented bikes and then public transport to commute from home to the workplace. On a leverage, it could create alternative mobility networks that reduce pressure on our failing transportation system.

Ensuring maintenance and inclusivity

The requirements are basic: regular cleaning where people gather. Basic seating where communities have claimed space. Toilets and drinking water—so fundamental that their absence becomes exclusion. Lighting for evening conversations, shading for afternoon gatherings. But real inclusivity means understanding what keeps different groups away. In our research, the same corner that welcomed young men felt threatening to women after dark, and the same tea stall that hosted vibrant gatherings excluded families because of traffic chaos. Any public space strategy must also ensure the inclusion of all people regardless of class, gender, religion, or age.

This requires understanding what urban designers Varna and Tiesdell call the “thresholds and gateways” that either welcome or exclude different groups. It means designing for “inclusiveness”—spaces that truly enhance diversity and “attract users across different ages, abilities, and socio-economic statuses.” Our research shows that genuinely inclusive spaces do not just serve more people—they create the social mixing that makes urban life vibrant and democratic.

Most importantly, we could trust communities to manage their own spaces rather than imposing external visions of order. The spaces with the highest levels of genuine “publicness” are invariably those where local people have real agency over how space gets used and maintained.

The true meaning of capital

We treat land as a commodity, not a community resource. But what if we remembered that cities also have use value—the capacity to generate encounter, creativity, and community?

French philosopher and socialist Henri Lefebvre explained this distinction. He wrote about cities as “oeuvre”—works of art created for human flourishing rather than mere products for exchange. This is precisely what quality public spaces enable: they become canvases for collective creativity. People gather to make music, paint, perform, celebrate—transforming ordinary spaces into living artworks.

Even in Dhaka’s most constrained conditions, we see this creative impulse wherever people can claim space—from the walls of Dhaka University transformed into “vibrant canvases that convey messages of understanding, harmony, and freedom of expression,” to the community-organised cultural events where street art, music, and performance create temporary stages for collective creativity. This creative energy is the true capital of any city—the human creativity, social bonds, and cultural vitality that no amount of infrastructure investment can purchase.

What is remarkable is how public spaces solve problems we did not realise we were addressing. That tree-lined gathering spot? It is cooling the neighbourhood by degrees. That community space in an abandoned lot? It is absorbing floodwater during monsoons—if we can design it sensitively. These spaces work multiple jobs—providing ecosystem services while building community, improving public health while strengthening social trust—creating numerous “positive externalities,” as economists term them. They make neighbourhoods resilient during crises (and we have many crises).

Breathing room for democracy

Sometimes Dhaka feels remarkably close to what Jane Jacobs envisioned—a city where density, diversity, and organic community create extraordinary urban vitality. What is missing is not the human energy or social creativity (we have that in abundance). It is the political courage to protect and enhance the spaces where this energy can flourish. Our agencies should inspire more private investment in public spaces—a tax rebate on such investment could be considered, and such private investment should be recognised as a form of corporate social responsibility. More critically, we are still far behind in including children, women, and the elderly in our commons. We need spaces where the mixing of differences creates the foundation for democratic life.

Although Dhaka residents are already reclaiming every available inch of common ground, quality remains an issue—specifically, cleanliness, prioritising pedestrians over vehicles, seating, and shading. The question is whether we will have the wisdom to listen to what our streets are already teaching us about the true meaning of urban capital. The commons are not a luxury we cannot afford—they are the foundation of everything we might become (if we choose to become it).

Arfar Razi, a planner, geographer, and Fulbright Scholar, coordinates the Academic Programme at Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements. Several analyses and visual materials presented here were collectively developed during “The Making of Publicness” workshop, organised by Bengal Institute with participation from diverse contributors.