October 2, 2025

DHAKA – This is not a book review. At least not in the traditional sense where the reviewer recaps the gist of a book, quoting and analyzing parts, drawing or pointing to conclusions. Arundhati Roy’s memoir Mother Mary Comes to Me is not something to be summarised. I believe if a reviewer tries to do so, they will only come up with much lesser versions of what Roy has already vividly painted in every page of this book of love—sorrow; eccentric, horrifying, strangely warm mother-daughter relationship; the eternal bond of a set of broken siblings; friendships; integrity; politics; injustice; rebellions; deaths; survival; living for one’s truths and lies; and healing—the overused yet inescapable word of our century.

What I will attempt instead is to list eight things this book might do to you. And in that you might identify yourself as a suitable reader of Roy’s memoir, or you might not— not until you are ready to face all the triggers, traumas and truces this memoir will press against you.

1. Mother Mary Comes to Me will confuse you about its actual protagonist. Mary Roy, Arundhati’s mother, whom she describes as her “gangster”, “shelter and storm”, will baffle and enrage you and then strangely make you giggle. In some pages you might even give her a standing ovation for her courage, commitment, and for being an important catalyst of change in children’s education and women’s rights. Arundhati will turn your heart around about what could have been one of the most insufferable real life characters you have ever read and open you to the complexity of human nature. You will experience both a super-human and a demon in Mary Roy. At times you will wonder about the humour. You will ask yourself if this is a caricature or did this person actually exist? You will be constantly tossing a coin with love and hate, cruelty and kindness, intelligence and incoherence, anger and helplessness embossed on opposite sides. You will keep changing your mind and realise life is inconclusive, and people are not squarely decipherable.

What I will attempt instead is to list eight things this book might do to you. And in that you might identify yourself as a suitable reader of Roy’s memoir, or you might not— not until you are ready to face all the triggers, traumas and truces this memoir will press against you.

2. If you are a woman who has lost your voice, suppressed your needs, or felt guilty for wanting to be different, you will locate your lost power in these pages and reclaim yourself. You will become less apologetic for wanting and needing what is essential for you. You will laugh at the conventions which have tied you to lethargic comforts, social obligations, invisible and visible patriarchy. You will see Arundhati and Mary as women who were ahead of their times, or perhaps they were right on time so that those who came later found the nerve to keep doing what these two ladies did for the first time, a second, third, fourth and hundredth time and if we are brave, to even go some extra miles.

3. The book will make you cry, laugh, pause, hurt. If you have had strict parents, you will go back to your childhood and reexamine events, motives. You will find new eyes to look at yourself and your vulnerableness and those of your parents. If you grew up fatherless, or with a parent who used you as a punching bag, you will find it almost unbearable to continue reading this book. Yet, you will read on. You will weep. And then, who knows, you might even find forgiveness.

4. If you are a fan of The God of Small Things (1997), Arundhati’s Booker Prize winning novel, you will love all the descriptions that wait for you in the first hundred pages. You will devour again the prose on the village of Ayemenem in Kerala, the Meenachil river, its fishes and fishermen, the rain, the forest and all the tiny heart-breakingly gorgeous things that the siblings Rahel and Estha lived amongst. The inspirations behind characters of Velutha, Chacko, Baby Kochamma will come alive. You will understand from where Arundhati picked up the themes of oppression, Naxal movement, intellectuals, elites, and outcasts.

5. You might stop labeling yourself according to the larger society’s definitions. You might pick up a pen and write down your confessions even if it is for your eyes only.

6. You will learn about a woman, Arundhati to be specific, who has an extraordinary capacity to love. Like her protagonist Anjum, from her second novel The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (2017) who builds a guest house in a graveyard and where each room contains a grave, you will see how—through her activism and life—Arundhati, too, has experienced the deaths of many close and important individuals. Individuals whose causes and sacrifices Arundhati believed in—unheard and mistreated individuals who came to her to be heard or to whom she ran to understand, witness and fight for the injustices they faced. Many of these individuals embraced deaths, some were forcefully killed. You will get a glimpse of the chambers holding each of their graves in Arundhati’s heart.

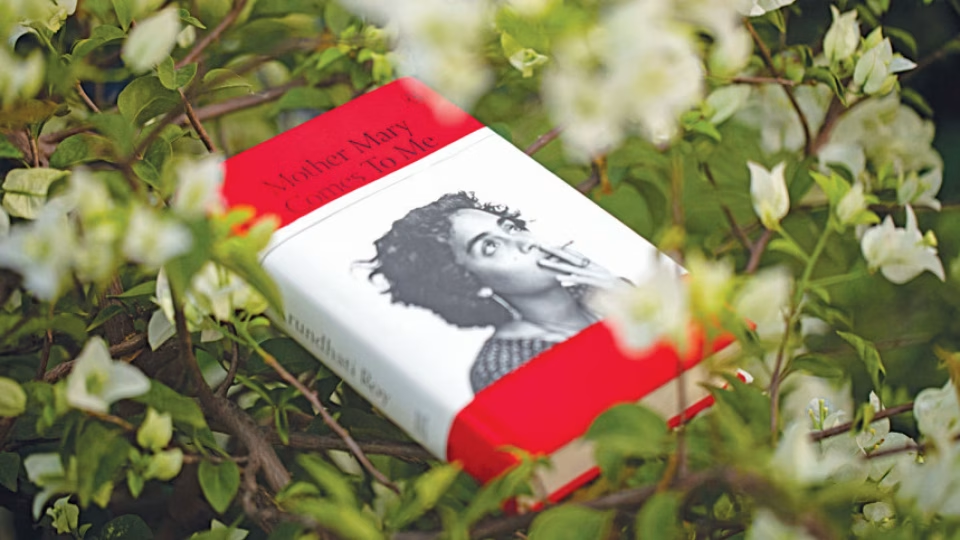

7. As the book wraps up and Mary Roy passes away, you will read a prolific description of her funeral and all that followed, including how and where her ashes were spread. And then suddenly you will look down at your hands and notice the book you are holding, Mother Mary Comes to Me, and recognise that this spectacularly designed red-almost-velvety covered book is also Mary’s ashes. Arundhati, in her most fantastic of ways, has given you a part of her mother. These thousands of copies now floating around various continents, in our hands are all but fragments of Mary Roy. We too now hold a piece of thorny love, thoroughly lived life, a thoughtful song, and triumphant celebration. Like that, you will touch what is most precious to the author and she will dig a new hole in your being and fill it with emotions that will make you feel drugged. You will want to be silent after you fathom all these.

8. You will walk away with these lines: (A) Anything Can Happen to Anyone. (B) It’s Best to Be Prepared.

Just like Arundhati Roy’s Rahel from The God of Small Things, and Anjum from The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, who lived with Roy as she wrote them out, Birongo is a vivid entity who lives with her author until she has her own complete novel to reside in, hopefully in thousands of prints around continents.