October 23, 2025

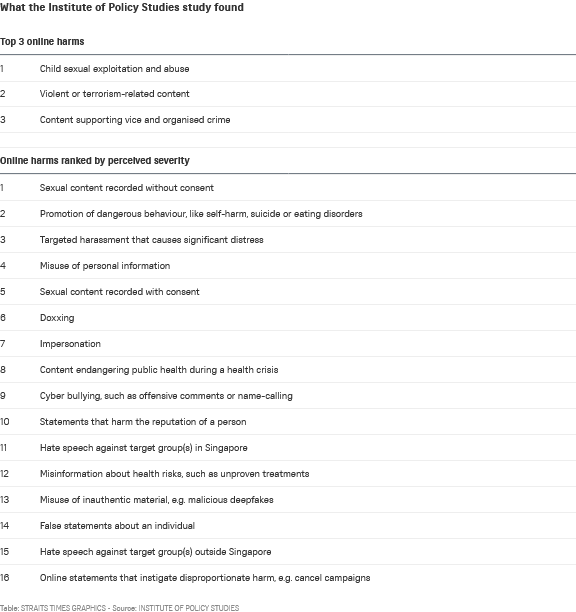

SINGAPORE – Singaporeans ranked non-consensual sexual content, promotion of dangerous behaviours like self-harm, and targeted harassment as among the most harmful online behaviours from a list of 16 harms, according to new research by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS).

The study, released on Oct 22, also indicated that some harms such as cyber bullying and catfishing have been normalised by younger respondents under 35, highlighting the need for more public education, said the researchers. Catfishing refers to the practice of luring someone into a relationship with a fake persona.

The year-long study, conducted between June 2024 and May 2025, involved a review of laws and social media platform rules, focus group studies and in-depth interviews with victims and supporters, and a survey of 600 Singaporeans and permanent residents.

Funded by the Ministry of Digital Development and Information, the study examined how Singaporeans perceive the severity of a wide range of harms, and what they make of existing laws, platform policies and public education efforts.

Researchers first found there was a broad consensus that child sexual exploitation and abuse, violent or terrorism-related content, and content supporting vice and organised crime were the most severe online harms.

However, there were other online harms where there were more nuanced opinions, and perceptions of severity also differed across demographics.

This list of 16 online harms, including acts such as doxing, impersonation and cyber bullying, was evaluated using a survey with 600 respondents. Participants were presented with 12 sets of questions.

Each question featured four randomised online harms, and participants were instructed to indicate the harms they perceived as the most and least severe.

Non-consensual sexual recordings were unanimously regarded by all age groups and both genders as the most severe online harm, said Dr Chew Han Ei, a senior research fellow at IPS, during a media briefing held on Oct 22.

Participants from in-depth interviews said that threats to release intimate images are a form of domestic violence that often goes under-recognised, which can often continue even after physical separation.

Next was the promotion of dangerous behaviours such as self-harm, suicide or eating disorders, a finding that surprised the team, said Dr Chew, who is also principal investigator of the study.

He said focus group discussions revealed that parents and youth counsellors were concerned about this online harm because of the disproportionate impact on young people, citing online groups where cutting and pro-anorexia content is shared.

With insights from the focus group discussions, the researchers said they were also concerned about the normalisation of some online harms, said Dr Chew.

“I worry that young people we talk to think it’s normal to meet with trolls and negative comments when we go online,” he said, adding that some young people also think catfishing is a harmless prank.

Dr Carol Soon, co-principal investigator of the study, said: “Normalisation is concerning to us because that may have long-term effects on them without their knowledge, and normalisation could also influence their behaviour towards their peers, and we know that what happens online can spill over into the offline world as well.”

To tackle normalisation, Dr Chew said all stakeholders, including tech companies, parents, educators and social service organisations, should have more conversations about what are acceptable norms in Singapore’s society.

The study also found broad support for stronger legislation to hold perpetrators of online harms accountable and to ensure victims have faster remedies.

Nearly eight in 10 respondents, or 79.3 per cent of them, said laws that hold perpetrators accountable would be “very” or “extremely” helpful, while 77.4 per cent wanted laws that can allow for the takedown of harmful online content.

The study also found that 77 per cent wanted harmful content and accounts removed more quickly by social media platforms.

A new Bill was tabled in Parliament on Oct 15 to allow for the set-up of the Online Safety Commission, where victims of non-consensual distribution of intimate photos, child abuse material and doxing will be able to seek timely redress.

Dr Soon, who is also deputy head of the communications and new media department at the National University of Singapore, said that during in-depth discussions, victims of online harms highlighted the swift removal of harmful content as a clear priority.

However, many victims are often confused by the reporting and takedown process of the various platforms, as each of them has different definitions for online harms and different procedures.

To address this gap, the researchers said policymakers and platforms should publish clear and regularly updated reporting guidelines and use plain language to explain legislative provisions.

“These guidelines should outline what are the reporting procedures, what are the various assessment criteria and what are the possible outcomes,” said Dr Soon.