November 25, 2025

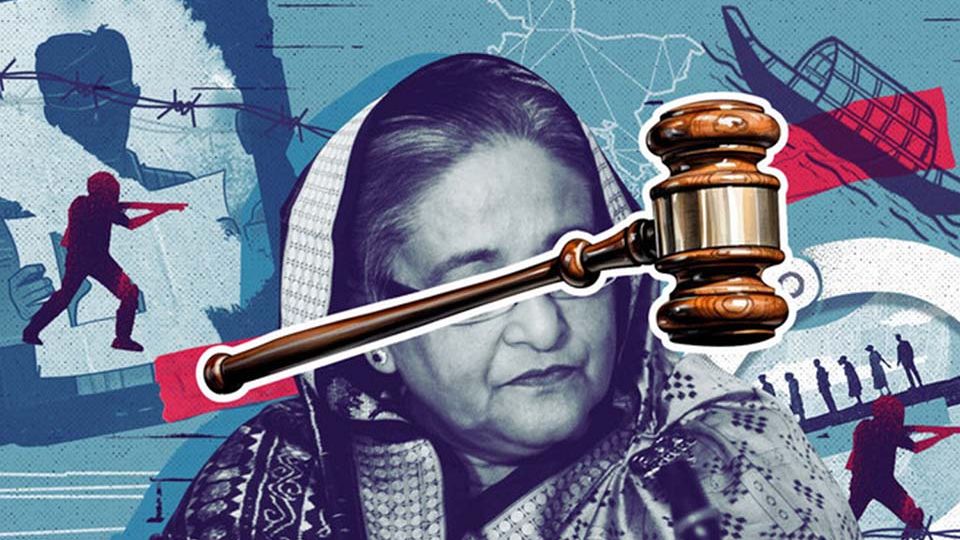

DHAKA – The verdict against Sheikh Hasina does not just condemn a former prime minister. It sentences an entire model of politics. The deeper question now is whether Awami League survives as a party, or only as a memory of fear and loyalty.

Awami League today is a textbook example of a personalist party. Scholars describe such parties as vehicles built around a single leader who controls nominations, finances, and coercive linkages between state and party far more than any committee does. In Bangladesh, party constitutions often speak of councils and presidiums, but in practice, the central working or executive committee has long revolved around one figure whose word can override procedure. When that figure is unseated, exiled, and now sentenced to death in absentia, three factors usually matter for the party’s fate: its brand, its machine, and the violence in its past.

The Awami League brand is split in two: one layer is the liberation memory and the promise of secular nationalism, which still hold sway among many loyalists; another is the experience of authoritarian rule from 2009 to 2024, which ended in regime collapse following a mass uprising. This constitutes what political scientists call a brand crisis. Voters who once associated the party with independence and development now also associate it with enforced disappearances, digital surveillance, images of students shot in broad daylight, etc.

The machine, however, remains real. For more than a decade, Awami League reshaped local power structures by tying local government, law enforcement, business contracts, and even relief distribution to partisan loyalty. Even after the interim government banned party activities and suspended its registration under the Anti-Terrorism Act, those ties did not magically vanish. What we see instead is a scattered, weakened, but still-resilient network of former lawmakers, chairmen, contractors, and student enforcers—some in prison or on the run, others quietly negotiating their survival with the new authorities.

At the top level, exile has created a parallel command structure. Recent reporting shows that Hasina and senior leaders coordinate shutdowns and protests from Kolkata, London, and other cities, using encrypted channels and sophisticated digital outreach that still engages supporters. This is not a dead party. It is a party stripped of legal recognition and territorial control but still armed with diaspora money, foreign connections, and an angry base. That combination can produce renewal, or catastrophe.

So, what are the realistic futures for Awami League without Hasina as a legal political actor inside Bangladesh?

The first scenario is fragmentation under new labels. Comparative research on authoritarian successor parties shows that even when a ruling party is banned, its cadres often reappear in new centrist or regional vehicles, especially where they still command local patronage and social capital. Former Awami League figures already face powerful incentives to reinvent themselves as independents or as leaders of new parties claiming to have broken with the Sheikh family cult while keeping the networks intact. Many small parties that joined the post-uprising coalition will quietly recruit these figures. Over time this may produce a landscape where there is no single Awami League, but many fragments of its old machine.

The second scenario is negotiated rehabilitation without Hasina. After bans and trials, discredited parties are sometimes re-legalised on strict conditions: lustration of condemned leaders, truth-telling about past crimes, and broader constitutional changes making concentration of power more difficult. The ongoing restrictions on Awami League and its student wing carry built-in conditionality tied to the outcomes of the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT), which has now issued the harshest possible verdict against its central figure. If the tribunal or any other competent court moves towards a collective judgment on the party, one compromise available to future elected governments will be to distinguish between the organisation and its former leadership. Down that path, a post-Hasina Awami League would have to accept written limits on dynastic control and internal democracy enforced not only by its constitution but also by electoral law and criminal procedure.

The difficulty in this scenario is that it requires someone inside the party with enough legitimacy to declare that the age of family rule is over. More likely, any attempt to relaunch Awami League as a legal entity will happen under a very different leadership coalition, one that comprises middle-ranking organisers and local notables who were never central to the security apparatus.

The third scenario is radicalisation in exile. The combination of a death sentence, an effective party ban, and frozen assets can produce a strong sense of victimhood. Diaspora networks can drift from lobbying and digital propaganda into funding or facilitating underground activities. Here lies a danger for Bangladesh—a slow erosion of the new institutions through constant attempts at sabotage, diplomatic pressure from sympathetic foreign patrons, and episodic violence by splinter groups that claim the Awami legacy but reject its secular connection. History offers many such examples, from armed offshoots of banned movements in Latin America to factions that turned to street-level militias after losing their constitutional space.

Which of these future scenarios unfolds depends less on Hasina herself and more on two other actors. The first is the interim and future elected governments, especially how they handle transitional justice. A process that looks like victor’s justice will push many ordinary Awami supporters towards denial and resentment, making exile narratives of persecution more plausible. But a process that separates individual criminal responsibility from collective guilt, and offers lower-ranking activists a clear pathway back into civic life, will weaken the appeal of militancy.

The second actor is the generation that toppled Hasina. Young people who braved bullets in 2024 and then organised through new parties and civic platforms will determine whether Awami League remains a toxic brand for life or can be recycled as one competitive option in a pluralistic system. Research on political generations indicates that experiences in late adolescence can leave deep partisan imprints. For many of these young citizens, the word “Awami” now evokes memories of checkpoints, trolls, and mothers waiting outside morgues. To rebuild legitimacy, any successor formation will need to acknowledge this trauma publicly, not bury it beneath slogans about development and liberation.

A prudent approach, therefore, will be to avoid two temptations. One is to treat Hasina’s death sentence as the final closing of a chapter and drive Awami League entirely out of politics; that path almost guarantees some form of underground politics and invites sympathetic foreign powers to use the exiled leadership as a bargaining chip. The other is to rehabilitate the party too quickly in the name of reconciliation without serious institutional reform, which would amount to inviting the same machine back under a fresh coat of paint.

An Awami League without Sheikh Hasina should be neither sacred nor forbidden. It should be forced to become ordinary. That means full accountability for crimes committed under its rule, strict campaign-finance transparency, internal elections that actually matter, and a constitutional environment that prevents any party from monopolising power again. The networks that long sustained the party will not disappear, but they can be tamed by new rules and higher expectations from citizens.

If that happens, the future Awami League may resemble what it has not been for a long time: a fallible political party competing for votes, not a dynasty backed by a security apparatus. Sheikh Hasina’s death sentence will still mark a key moment. But it may also become the point at which Bangladesh finally separates liberation memory from impunity and replaces fear with institutions.

Arifur Rahaman is a PhD student at the Department of Political Science at University of Alabama in the US.

Views expressed in this article are the author’s own.