April 1, 2022

SEOUL – South Korea retreated from its pandemic response strategy known as “test, trace, treat” on the premise that with omicron, COVID-19 had transformed into a more flu-like disease. Omicron’s emergence called for a new strategy “attuned to the changes in the characteristics of the virus” and a departure from the earlier ways of handling the pandemic, health officials have said.

The touted promise of a milder virus is fading by the day so far into Korea’s omicron journey. The pandemic situation here has taken a grim turn, with the new variant killing and hospitalizing more people than any of its predecessors.

‘Omicron will set us free’

The omicron plan kicked off nationwide two days after the variant’s share of weekly analyzed cases crossed 50 percent on Jan. 24. With the plan, the country did away with most measures to control the outbreak and manage patients.

Contact tracing came to an end, and the isolation period for people with COVID-19 was cut to seven days after receiving the initial positive test. Eventually, quarantine requirements for close contacts were scrapped. Access to resources like polymerase chain reaction tests became restricted, reserved primarily for people 60 and older.

This policy shift at the dawn of the omicron age was guided by the notion that a surge led by the milder virus could help the country reach the endemic stage.

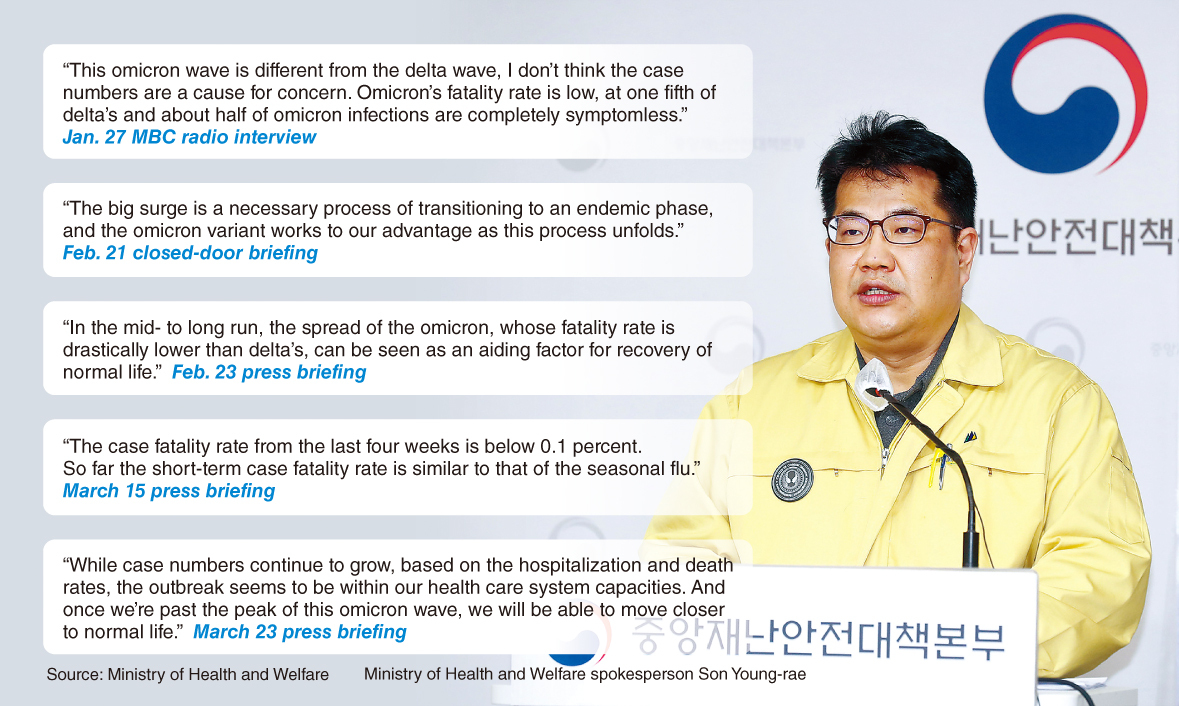

“This isn’t like delta,” Ministry of Health and Welfare spokesperson Son Young-rae explained during a press briefing on Jan. 26.

“While cases may increase for the time being, I believe that our response system will be able to minimize the damage overall,” he said, urging people to “trust the science that public health authorities provide, and don’t panic over the numbers.”

He said omicron was only one-fifth as deadly as the previously dominant delta variant — an estimate that was later corrected as half or one-third — and believed to cause less harm.

Among people younger than 60, omicron’s fatality rate was “nearly zero percent.” All in all, omicron was turning out to be about as fatal as the seasonal flu, he said, although for unvaccinated and older adults, it was a different story.

Still dangerous for some but mild and flu-like for most, omicron warranted “targeted protection of high-risk groups,” he said.

Two months after the plan was implemented, Korea is witnessing some of the highest new infection and death rates worldwide. Son told reporters on March 23 that this was “inevitable.” “It had to happen at one point or another,” he said. He said once the surge is past, however, the country would be rewarded with possible progression toward the goal of normal life.

Dr. Jung Jae-hun, COVID-19 advisor to the prime minister, said in a Facebook post on Jan. 20 that the omicron wave “may be in a way, the final big surge in this pandemic, and a period during which we make a fundamental transition in our society’s response to the pandemic.” In another post, on Feb. 4, he said, “After we can confirm the peak of the wave is past, we can begin to pursue an exit strategy.”

“We’re nearing the final chapter of our journey that has gone on for more than two years,” he said. “I hope together we can get through this crisis that is close to being the last.”

Great Barrington Declaration’s omicron revival

The rationale for the omicron plan is that the intensive social distancing of the delta days is “no longer viable nor cost-efficient,” according to the Health Ministry spokesperson on March 2. And as omicron is milder, doing so would pose little threat to the population.

Similarly, Jeong Eun-kyeong, commissioner of the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, said at a March 21 briefing that “as there already has been substantial exposure in the community due to omicron’s high transmissibility, controlling the outbreak with social distancing alone will have significant limits.”

But the focus on social distancing eclipses what health officials should do without having to ask people to stay home and relive the intense isolation of the early pandemic days, according to public health professor Dr. Oh Ju-hwan of Seoul National University.

By using social distancing as a “blanket term” for pandemic control measures, health officials sold people on the idea that we no longer had to sacrifice freedoms to contain the virus, he said. “The narrative that social distancing is the only approach is misleading, and it’s been used as an excuse for authorities to do less of what they ought to be doing.”

With omicron’s rise, first to be abandoned were measures that exact the most administrative burdens, like extensive contact tracing and testing that Korea had prided itself on, he said. While quick to remove the no-cost testing-for-all policy and contact tracing, health officials kept social distancing restrictions, though eased, for the public. The cap on the size of personal gatherings and nighttime curfews for stores are still in effect, though they are anticipated to be removed soon.

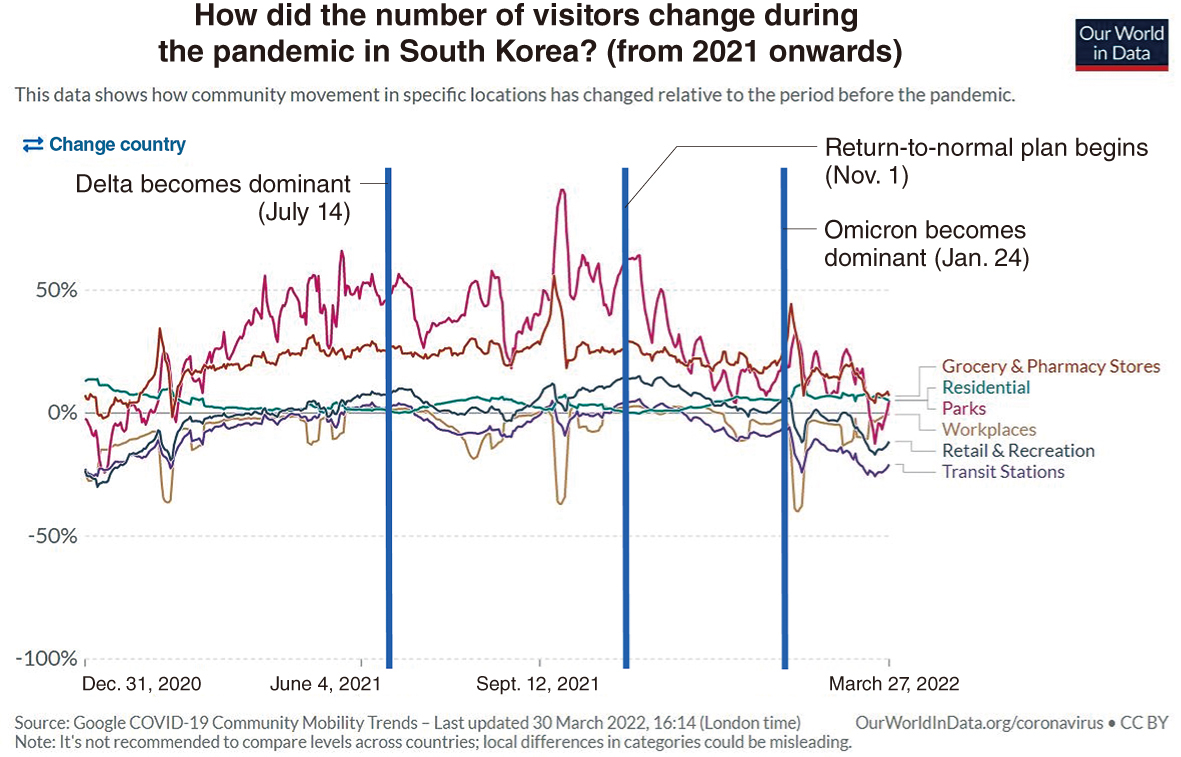

(Our World in Data)

Google mobility trends shows movements have been on a decline in Korea after omicron took over as the dominant virus in late January. Visits to retail and recreation facilities especially have fallen considerably compared to when the delta variant was raging across the country in the fall of 2021.

“When cases soar and hospitals fill up, people exercise caution voluntarily,” Oh said. “The mobility trends data demonstrates that the surge we’re seeing now is not in fact attributable to the lack of social distancing, as some officials and experts suggest.”

Although health officials like to emphasize the pains of social distancing, and how they are no longer sustainable, what was glaringly absent were efforts to test and trace cases and grasp the true scale of the outbreak, he said.

Active tracing was also crucial to “monitor variants, as letting the virus run amok in the community gives it more opportunities to evolve,” he said.

Oh said the omicron response strategy of naturally infecting kids, and hybrid infecting adults while shielding only the vulnerable is deja vu of the Great Barrington Declaration from the first year of the pandemic. The declaration argued for focused protection of high-risk populations while letting those not considered to be as at-risk live near-normal lives.

Unlike when the declaration was penned, now there are vaccines and treatments. But evidence is still scarce that natural immunity attained through omicron infection will offer reliable protection against the next variant outbreaks, he said.

“If natural immunity is indeed superior, then contracting a mild disease would be considered a blessing, which it is not,” he said. “The ‘super immunity’ from a combination of vaccination and natural infection is at best an assumption at this point.”

In fact, data pointing to the contrary is emerging. A study published March 17 in the journal Cell said omicron breakthrough infections are “less immunogenic than delta, thus providing reduced protection against reinfection or infection from future variants.” A preprint study posted March 23 said reinfection with the COVID-19 virus “occurs regularly, and can amount to a significant population level.” The absolute burden of reinfections “may become substantial for health systems,” it said.

“Korea is plowing through with the omicron plan at the cost of record deaths and hospitalizations on this assumption that at the end of the wave, protective levels of immunity will be established in the community that will allow us to return to normalcy,” Oh said.

“But if we’re wrong — and there’s a high chance we just might be — then so many people would have died for nothing, they’re not even collateral damage.”

Koreans dying more than ever in omicron wave

Omicron’s impact on fatality trends is clear. Since omicron’s dominance, it took 54 days for the total confirmed COVID-19 deaths in Korea to double, from 6,712 total deaths on Jan. 28 to 13,432 total deaths on March 22.

The one-day high of 469 COVID-19 deaths reached on March 23 — which translates to about 6 deaths occurring per 1 million people on a seven-day rolling average — is higher than deaths seen in many other developed economies at the height of their respective omicron waves. The UK’s omicron wave peaked at 4 deaths per 1 million on Jan. 18, and Australia’s at 3 per 1 million on Jan. 29. The high death counts here have occurred as the worst of omicron is likely still to come.

While the official death toll is already staggering, it is important to remember the actual number of deaths can only grow larger, according to Dr. Lee Jong-koo, a former Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention chief.

Lee, who headed the national health protection agency through the H1N1 flu pandemic in 2009, said Korea was “in essence pursuing a natural immunity strategy,” which “has no basis on science and evidence.” “No one has explicitly admitted this, but that seems to be what we are doing, and this is backfiring with terrible consequences,” he said.

More than 350 people in Korea have died each day over the past week. The 8,172 deaths registered in March accounted for about half of the known 16,230 deaths accumulated since the beginning of the pandemic.

(Our World in Data)

“Never had so many people died from an infectious disease in one day,” Lee said.

As the omicron wave overwhelms hospitals, people who would have lived under normal circumstances have been dying from a lack of or delay in access to care, he said. “This is what we call ‘excess’ deaths.”

Statistics Korea noted in its March 14 report that since September last year, monthly deaths “have consistently surpassed” rates observed in the three preceding years.

The increase in extra deaths was particularly stark in older people. At the height of a post-reopening hospital bed crisis in last December, excess mortality rate rose by 18 percent in people ages 65-84 and by 21 percent in those older compared to the three-year average number of deaths from the same month in 2018-2020.

The Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, formerly the Korea CDC, reports that more than 95 percent of omicron deaths were occurring in people 60 or older.

The rate at which omicron is killing older people could lead to a fall in the country’s average age by summer, according to infectious disease professor Dr. Kim Woo-joo of Korea University. “It’s like living through a senicidal nightmare,” he said.

Kim said the reduced severity of omicron was offset by its ability to spread and sicken so many people at once.

“Omicron wave’s absolute toll is not being considered in the policy decisions, with the fixture on its decreased virulence relative to delta,” he said. “But fathom this. Even if the possibility of dying from omicron is 10 times lower, if 10 times more people become infected, then ultimately the damages will cancel out whatever benefits of the milder severity.”

In the last decade the winter flu at its worst killed about 720 people a year, according to Statistics Korea data. Kim, who headed the national influenza centers from 1991 to 2001, said the true figure is probably closer to 2,000 to 3,000. Still, in just the two weeks from March 8-21, omicron managed to kill 3,661 people.

As deaths pile up, crematoriums and funeral homes across the country are struggling to keep pace. According to the Health Ministry, in the first two weeks of March an average of 1,100 bodies were cremated each day, which is about 391 higher than the three-year daily average of 719 in the same month in 2018-2020. The unprecedented rise in the deceased awaiting cremation led to the Health Ministry ordering public crematories on March 16 to extend their operating hours.

“From how I see it, nothing justifies 300 to 400 people dying every day with morgues running out of space for bodies. The worst part is we don’t know if this is going to be the last of the virus,” Kim of Korea University said.

Chief infectious disease specialist Dr. Eom Joong-sik of Gachon University Medical Center, a state-designated COVID-19 hospital near Seoul, said his hospital recently ordered extra morgue refrigerators. “The omicron wave is by far the worst we’ve experienced in the pandemic. With flu comparisons we’re forgetting the rates we’re seeing now is a result of masking, populationwide vaccination, distancing — something we don’t do with flu.”

Like waves at the beach

Dr. Jerome Kim, the director-general of the International Vaccine Institute, warned against thinking that the omicron wave is the endgame.

“Health officials should realize it is difficult to turn the dial back. They should not raise expectations,” he said.

“We have to think of this in dynamic, not static — like the flu — annual terms. This is more like waves at a beach, one after another. Will the next one be more infectious and a tad more serious? Possibly. Or equally severe? Possibly. Not like the flu.”

From countries hit earlier by omicron it is evident that reinfection “within two months is possible, or not uncommon,” he said, which is also unlike the flu.

“Omicron and its ‘spawn’ BA.2, recombinants and more variants are able to reinfect those who were previously infected and put enough people in the hospital to use up 1,100 ICU beds. Also, not like the flu. Europe is resurging after the omicron wave, also not like the flu. An emerging subvariant is taking over from the original omicron. Also not like the flu.”

He said even after the omicron wave recedes, Korea would still be left with a large enough susceptible population to be potentially hurt by another wave within a few months because of the quickly waning immunity and the virus’s tendency to reinfect easily.

“If 25 percent of the Korean population ends up being infected, that still leaves 75 percent to become infected if a variant or subvariant similar to omicron appears, or gets reintroduced from a country that has it three to four months from now,” he said.

“While natural infection and vaccination may prevent bad outcomes like death, it may not prevent enough infections, and ICUs could fill up again.”