April 28, 2022

HONG KONG, NEW DELHI AND KOLKATA – Numerous difficulties experienced in attending online classes

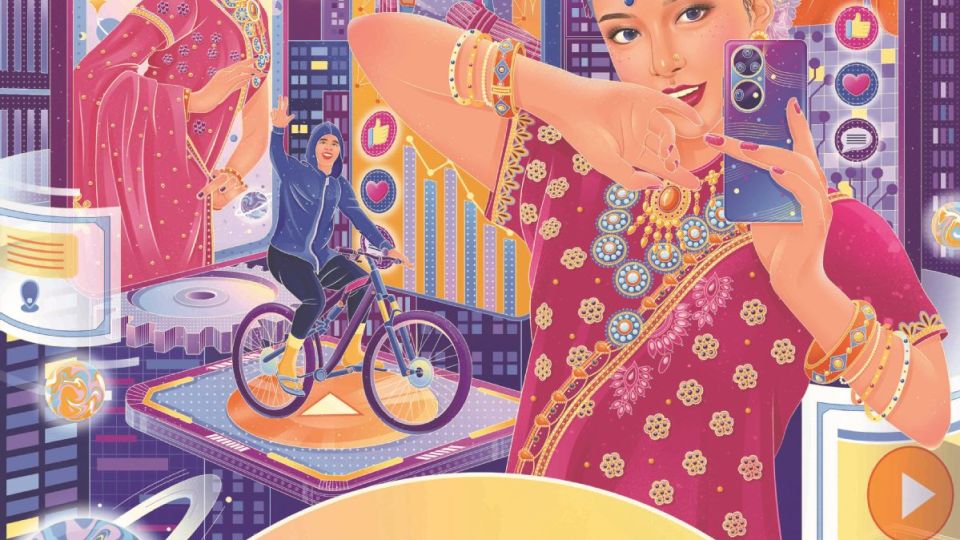

A ban on Chinese apps initiated by the Indian government almost two years ago came as a shock for Gauri, a content creator from New Delhi on the popular short video platform TikTok, who lost more than 6 million followers in one go.

“It was not easy to see the app go offline almost overnight,” said the young woman, who only wanted to be known by her first name.

“It was extremely painful, because it took a lot of hard work to build a follower base.”

For many workers such as Gauri, TikTok was a full-time occupation. As a social media outlet, the app offered numerous people living in smaller towns in India a platform to showcase their talent.

“This is why I couldn’t believe it when I heard of the ban,” Gauri said, adding that TikTok was an “amazing and diverse platform”.

For Ravi, a dancer from an impoverished family in Saharanpur, a small town in Uttar Pradesh state, TikTok was a good way to earn a living from his base of 7 million followers. He also struck partnership deals with local and national brands in India.

But following the ban, this income has dried up. Although he has shifted to other domestically produced short-video apps, Ravi has had to start from scratch. “This was not easy,” he said.

In mid-February, India’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology blocked access to 54 Chinese apps, stating that they posed a threat to national security.

The banned apps include: Beauty Camera: Sweet Selfie HD; Beauty Camera-Selfie Camera; Bass Booster& Equalizer; CamCard for SalesForce Ent; Isoland 2: Ashes of Time Lite; Viva Video Editor; Tencent Xriver; Onmyoji Chess; Onmyoji Arena; AppLock; and Dual Space Lite. The operators of many of these apps looked to India as an opportunity for growth.

The list of apps also includes some that were banned earlier by the Indian government, but which had rebranded themselves or relaunched under new names. After official confirmation and establishing the country of origin, further notifications were issued to block access to the apps, according to ministry sources.

Since June 2020, the Indian government has banned more than 200 Chinese apps. While 118 of them, including the popular game PUBG Online, were banned in September that year, 59 apps, including TikTok, SHAREit, WeChat, Helo, Likee and UC News, were blocked two months later.

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology cited Section 69A of the IT Act, 2000, stating that the way the apps compiled, mined and profiled users’ data posed risks to national security and defense.

With smartphones becoming a way of life for a growing number of users, apps serve as gateways to the digital world in India, where there were more than 700 million internet users in 2020. This figure is expected to rise to 900 million by 2025.

Based on downloads, India is the second-largest app market globally, with more than 25 billion downloads registered last year.

Sandeep Sengupta, managing director of the Indian School of Anti-Hacking Data Securities, which is based in Kolkata, said about 500 million Indians have embraced the “digital way of life” in the past six years. Indians are keen to stay connected online to a variety of digital platforms and products, he added.

By a rough estimate, smartphones produced in China account for nearly 60 percent of the Indian market. According to Indian media reports, many of the banned apps are already installed on these phones.

Experts said that no matter the reasons for banning the apps, the decision has been bad news for users in India and industries in both countries.

Many Indian technology experts said they used WeChat to stay in touch with key officials at tech companies headquartered in China.

Problems mount

The decision to block access to the apps has posed problems for thousands of Indian students, who face difficulties attending online classes in China from India.

China has not yet reopened its borders to foreign students enrolled at the nation’s universities. Indian students who have returned home from China amid the COVID-19 pandemic continue to face problems attending online classes, as China uses domestically produced apps to conduct them.

Tarun Dev, a student from New Delhi, enrolled with Wuhan University, Hubei province, in December 2020 for a Chinese-language program, but he was forced to halt his studies after finding it hard to attend online classes as a result of the ban.

Supradip Das, from West Bengal, who is enrolled with Beijing Language and Culture University, faced similar difficulties. Pursuing a Chinese-language degree course, he returned to India during the winter break in January 2020, as he was unable to attend many online classes after the ban was introduced. Das subsequently decided not to return to China for his studies.

According to the Indian embassy in Beijing, during the COVID-19 outbreak, some 23,000 Indian students are enrolled at educational institutions in China-mainly medical colleges. Most Indian students returned home from China in February 2020 because of the pandemic.

Students said the ban is hampering their studies because Chinese universities use domestically produced apps such as WeChat and SuperStar, along with Ding-Talk, Baidu translate, Youku, Sina Weibo, QQ and QQnewsfeed, which are now blocked in India.

Nagmani, an Indian student enrolled at Jinan University in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, who is studying for a bachelor of medicine and bachelor of surgery degree, said: “Connecting to a VPN to access these apps slows the system. As returning to offline classes is not possible at present, lifting the ban on these apps could at least provide some relief for us.”

Thousands of Indian students have no idea when they will be able to return to China for their studies.

Reacting to the decision to ban the apps, China’s Ministry of Commerce urged India to improve its business environment and treat all foreign investors, including Chinese companies, in a fair, transparent and non-discriminatory manner.

After the ban was introduced, ministry spokesman Gao Feng said China and India are inseparable neighbors and important economic and trade partners. Last year, the trade volume between the two nations reached $125.7 billion, a year-on-year rise of 43 per cent.

Murali Kallummal, a professor at the Center for WTO Studies at the Indian Institute of Foreign Trade in New Delhi, said the apps ban may also affect trade in services between the two countries and the confidence of Chinese companies doing business in India.

As most of the apps center on entertainment, this may affect business directly, Murali said. More important, it may take India some time to introduce new apps to replace those it has banned, but the sooner it does so, the better, he added.

After the ban was announced, WeChat, which is owned by Tencent, stated in a letter to users: “Pursuant to Indian law, we are unable to offer you WeChat at this time. We value each of our users, and data security and privacy are of utmost importance to us. We are engaging with relevant authorities and hope to be able to resume service in the future.”

WeChat began operating in India in 2013, when instant messaging was becoming popular. In just a few years it created a wide customer base.

S. Ghosh, who used to work in the international department at Sister Nivedita University in Kolkata, said she used WeChat to contact many of her counterparts in China.

“As a communication app, WeChat was useful,” she said.

TikTok, a product of Chinese company Bytedance, is also on the banned list. According to media reports, operators of the banned apps made persistent attempts to address India’s concerns, but they appear to have failed in their efforts, as the Indian government has stuck to its decision.

A former ByteDance employee, who requested anonymity, has been struggling to figure out why TikTok was banned.

ByteDance had no option but to largely close its office in India, said the former staff member, who has been jobless for months.

“The company tried hard to protect our jobs, but failed. Almost all 3,000 employees who lost their jobs were Indians.”

Heavy blow

Numerous clones, including MX Takatak, a short-video community app created by MX Media & Entertainment, have sprung up in India.

The decision to block TikTok dealt a heavy blow to ByteDance’s local staff members, but it also appears to have robbed thousands of young content creators living across India in big cities and small towns of ways to make a living.

The former Bytedance employee said, “This all happened at the height of the pandemic, when losing jobs was scary.”

He added that after it was banned and its operations largely closed down, Byte-Dance organized a series of online training and career grooming programs, along with guest lectures. The company also paid salaries and bonuses, and offered incentives for four months, even after workers had been given their notice and the business had no revenue in India due to the ban.

“We continue to be covered under the company’s health insurance plan for two years. Few companies in the world would show such a humane approach,” said the former employee, adding that the company is continuing with its operations in Europe and the United States.

Compared with TikTok and PUBG Online, which boasted more than 200 million and 50 million users respectively in 2020 before being banned, many of the apps subject to later bans only have tens of thousands of users in India.

Swaran Singh, professor of diplomacy and disarmament at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, said that apart from security fears, India has been concerned about China being the largest source for India’s imports. He suggested that enhancing mutual trust between the two countries could help address the issue.

He also believes that the apps ban is aimed at redressing India’s security concerns, and that it can “create new opportunities for local startups’ efforts to create more locally grounded alternatives”.

Chen Jixiang, professor and deputy director of the Center for Indian Studies at the Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences, said India banned Chinese apps mainly due to protectionism.

The ban can curb Chinese investment in India to make room for the growth of domestic enterprises, Chen said.

Wang Peng, a Distinguished Research Fellow at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, Hubei province, said banning the Chinese apps is contrary to the international business order and “against market or contract spirit”.

He added that if the Indian government considers that these apps have mined users’ data, it needs to provide evidence of this.

“This decision caters to monopolistic enterprises in the country, and helps Indian companies get rid of Chinese competitors after reaping benefits from them,” Wang said.

Sengupta, from the Indian School of Anti-Hacking Data Securities, said the Indian government had clearly done what it thought best for the country and its people, but “the decision certainly needs greater clarity and clearer explanations” of how the apps could “pose a serious threat to India’s security”.

He said if the Indian government explained the apps’ “harmful side”, this would enable the public to better understand why such serious measures were taken.

Sengupta also stressed the need to spell out the potential best substitutes for the banned apps, urging the Indian government to recommend substitutes that are safe and secure.

“This action is needed to ensure that life is not disrupted,” he added. “In the absence of such explanations, people may become confused. Worse, they may even look for ways to use these banned apps.”