August 4, 2022

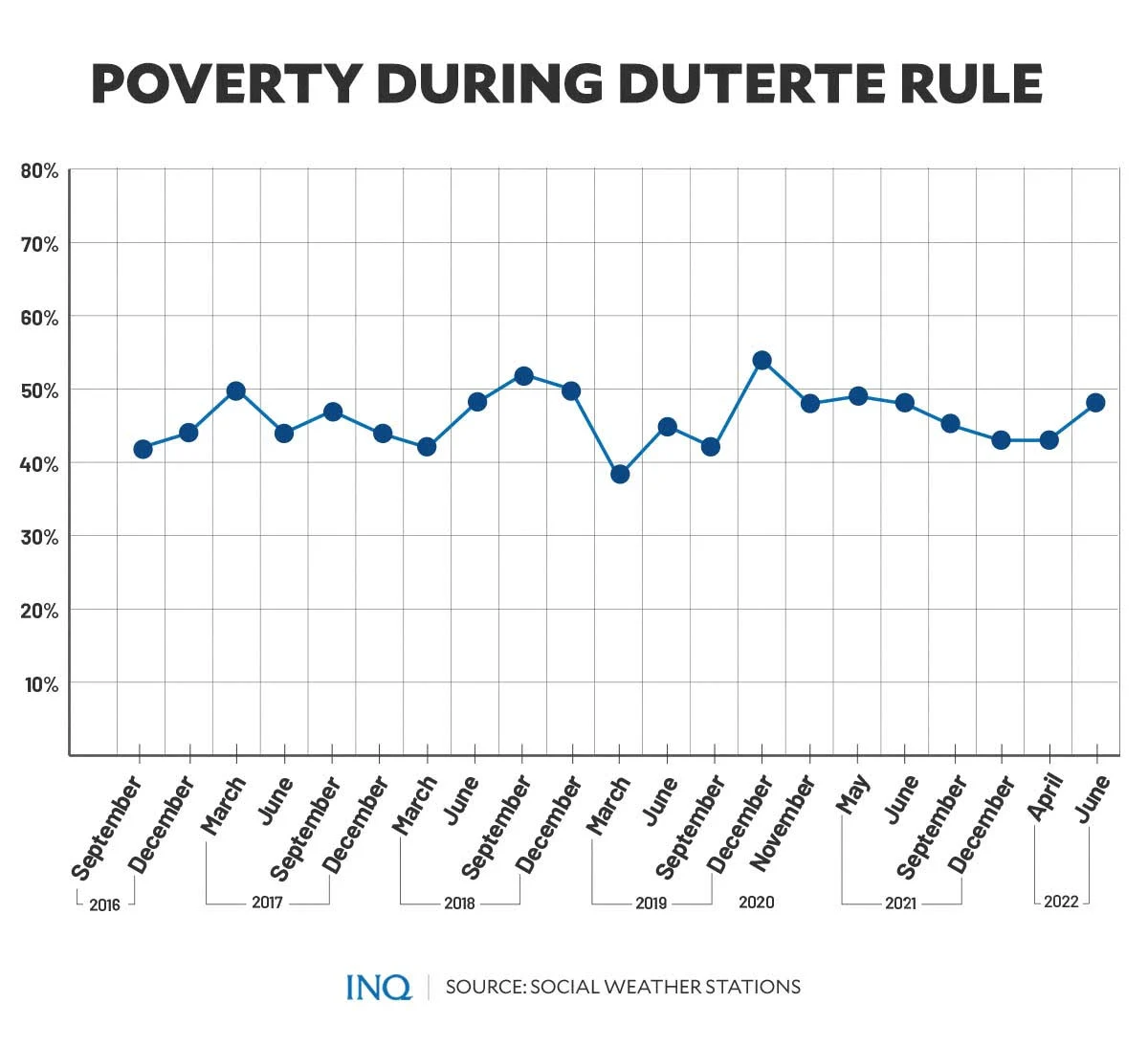

MANILA — As Rodrigo Duterte, who once promised a comfortable life for all Filipinos, ended his six-year presidency last June 30, 48 percent of Filipino households felt “poor” in the second quarter of 2022.

He said in 2018 that with all the programs being implemented by the government, the life of all Filipinos would get better in the third year of his presidency: “Konting tiis na lang (A little more patience).”

Then in 2019, Malacañang stressed that with the signing of new laws, like the Magna Carta of the Poor, the government was working to significantly reduce poverty rates and make poor Filipinos’ lives better.

The Social Weather Stations (SWS), however, said the percentage of Filipino families, who rated themselves poor, hit 54 percent, or 13.1 million households, in December 2019, the highest in five years.

This, even if Duterte had asked Congress in his 2019 State of the Nation Address to help the government lift six million Filipinos out of poverty by the end of his six-year presidency.

Last April 27, the National Economic Development Authority (Neda) said the programs of the government had contributed to reducing poverty, stressing that six million Filipinos were lifted out of poverty in 2018.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

However, as Duterte left Malacañang, a survey by the SWS showed that 12.2 million families considered themselves poor, higher than the 43 percent, or 10.9 million in April 2022.

Out of a respondent base of 1,500 Filipinos 18 years and older who were polled last June 26 to 29, 31 percent were “borderline poor,” while only 21 percent were “not poor.” Compared to April 2022, the numbers fell from 34 percent and 23 percent.

Neda said the government, back in 2016, had pursued the zero-to-ten point socioeconomic agenda to achieve the Ambisyon Natin 2040, a vision that reflects the “collective aspiration to end extreme poverty by 2040.”

While then Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Karl Chua said six million Filipinos had already been lifted out of poverty in 2018, “the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily halted our progress.”

He said last year: “In 2020, people’s income and jobs were significantly affected by stringent quarantines. As we began to cope with the virus starting the fourth quarter of 2020, we gradually relaxed restrictions and managed risks better.”

The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) said poverty incidence fell from 27.6 percent in 2015’s first half to 21.1 percent in 2018’s first half, however, in 2021’s first half, poverty incidence rose to 23.7 percent, or 3.9 million more Filipinos living in poverty.

SWS have been conducting self-rated poverty surveys since 1992, except in the first nine months of 2020, when face-to-face interviews were not possible because of COVID-19 restrictions.

When it resumed its surveys in November 2020, 48 percent of Filipino families considered themselves poor; May 2021 (49 percent); June 2021 (48 percent); September 2021 (45 percent); and December 2021 (43 percent).

Hits, misses

The government said that based on PSA data, poverty incidence fell to 16.6 percent from 23.3 percent in 2015, with the Neda saying that with a yearly poverty reduction rate of 2.23 percent, “we are on track” to end extreme poverty.

However, the think tank Ibon Foundation stressed that the way the government counts the poor “grossly underestimates Philippine poverty,” saying that many poor Filipinos are not counted.

The Social Reform and Poverty Alleviation Act defines “poor” as individuals and families whose incomes fall below the poverty threshold as defined by the Neda or cannot afford in a sustained manner to meet their minimum basic needs.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Because of this, the number of poor is counted as the number of Filipinos whose incomes fall below the poverty threshold or the minimum amount needed to meet basic food and non-food needs, Ibon Foundation said.

It first computes the subsistence threshold, or the minimum amount a family needs to meet basic food needs. This is then assumed to be 70 percent of the poverty threshold where the balance of 30 percent is assumed enough to meet basic non-food needs.

However, poverty estimates based on this methodology are low and unrealistic: “The monthly poverty threshold is just P10,727 for a family of five. This is just around P71 per person per day at P50 for food needs and P21 for non-food needs.”

Ibon Foundation said the “low standards” was the reason for the decrease in poverty incidence in 2018: “Persistently low poverty thresholds and illusory reductions in poverty will only result in persistent neglect of the needs of the many.”

Making do with what they have

The SWS said the rise in self-rated poverty was because of the increases in the Visayas and Metro Manila, combined with slight increases in Mindanao and Balance Luzon, or Luzon outside Metro Manila.

Compared to April 2022, self-rated poverty rose in the Visayas from 48 percent to 64 percent, and in Metro Manila from 32 percent to 41 percent. It rose slightly in Mindanao from 60 percent to 62 percent, and in Balance Luzon from 35 percent to 36 percent.

Out of the estimated 12.2 million poor Filipino families, 2.2 million were newly poor, 1.6 million were usually poor, and 8.4 million were always poor. Back in April, 1.5 million were newly poor, 1.1 million were usually poor, and 8.2 million were always poor.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The median self-rated poverty threshold—the minimum monthly budget that a family needs to stay out of poverty—stayed at P15,000, while the median self-rated poverty gap (difference between actual income and poverty line) stayed at P6,000.

This, as the threshold in Metro Manila fell from P20,000 to P15,000, while the gap fell from 10,000 to P5,000. In Balance Luzon, the threshold stayed at P15,000, while the gap rose from P5,000 to P7,000.

The threshold in the Visayas rose from P15,000 to a new record-high P20,000, while the gap rose from P7,000 to P9,000. In Mindanao, the threshold fell from P12,000 to P10,000, while the gap stayed at P5,000.

SWS said the self-rated poverty threshold has remained “sluggish” for several years despite considerable inflation: “This indicates that poor families have been lowering their living standards, i.e., belt-tightening.”

It stressed that the self-rated poverty gap in the past has generally been half of the median self-rated poverty threshold, saying that “this means that average poor families lack about half of what they need to not consider themselves as poor.”

The Philippines’ headline inflation rate in June 2022 hit 6.1 percent, a three-year high since November 2018’s 6.1 percent and October 2018’s 6.9 percent, because of higher yearly growth rate in the prices of food and non-alcoholic beverages.

According to SWS, based on the type of food eaten by their families, the June 2022 survey found 34 percent of families rating themselves as food-poor, 40 percent rating themselves as borderline food-poor, and 26 percent rating themselves not food-poor.

Compared to April 2022, the percentage of food-poor families rose from 31 percent, borderline food-poor families fell from 45 percent, and not food-poor families rose slightly from 24 percent.

The estimated numbers of self-rated food poor families are 8.7 million in June 2022 and 7.9 million in April 2022.

The three-point increase in self-rated food-poor from April 2022 to June 2022 was due to increases in Metro Manila, Balance Luzon, and the Visayas, combined with a slight decrease in Mindanao.

Compared to April 2022, self-rated food-poverty rose in Metro Manila from 25 percent to 31 percent, in Balance Luzon from 24 percent to 28 percent, and in the Visayas from 31 percent to 37 percent. It fell in Mindanao from 49 percent to 45 percent.

‘Recovery is hollow’

Sonny Africa, executive director of Ibon Foundation, told INQUIRER.net that the rise in self-rated poverty is “very understandable and confirms how the outgoing economic team’s claims of recovery are hollow.”

“Despite hype about rapid growth, ordinary Filipinos still suffer massive joblessness and high prices. For instance, of the supposed increase in net employment between January 2020 and May 2022, 93 percent is in just part-time work which grew to 16.7 million.”

By class of worker, 32 percent of the employed is in unpaid family work—3.8 million—and 56 percent is in poorly-earning self-employment, Africa said while stressing that the number of families without savings has grown to at least 18.7 million.

The PSA said last July 7 that six percent—2.93 million Filipinos—were jobless in May, slightly higher than the 5.7 percent, or 2.76 million jobless Filipinos in April. Employment rate was 94 percent, or 46.08 million.

However, Ibon Foundation said the latest PSA data indicated that the Philippines has the “worst” unemployment rate in Southeast Asia, saying that six percent is higher than Indonesia’s 5.8 percent and Malaysia’s 3.9 percent.

It said while there were 28.9 million Filipinos who worked for 40 hours and more in May, 16.7 million worked for only less than 40 hours and 500,000 had a job, but not at work.

Breaking down the 46.08 million employed Filipinos, 13.2 million were self-employed without an employee, 939,000 were employed in own farm or business, 3.8 million were unpaid family workers, and 28.2 million were wage and salary workers.

“The new economic team needs to urgently acknowledge this. Unfortunately the refusal to give more ayuda in the last months of 2022, the 2023 austerity budget and rising interest rates will just prolong the socioeconomic distress of millions,” he said.