July 16, 2019

Dismissing sci-fi and fantasy as low-brow or trashy isn’t just a desi stance, although it might be more pronounced.

My first encounter with a work of desi science fiction was very much by accident.

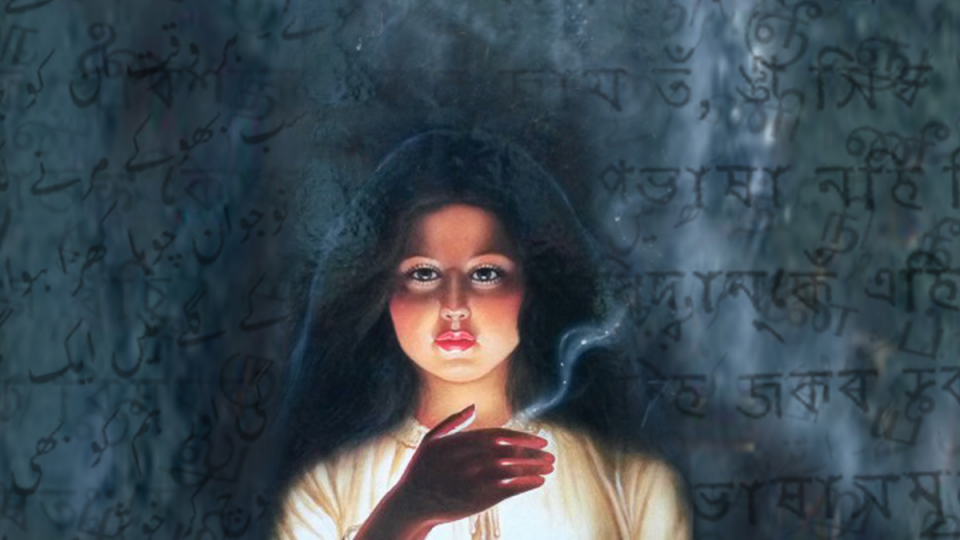

During my undergraduate studies at the English department at Karachi University, while idly browsing through a professor’s personal collection on her desk, I came across Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s Sultana’s Dream, a English-language short story set in a feminist utopian world written by a Bengali Muslim woman in 20th century colonial India.

Up until then, my study of literature had been mostly white, mostly male authors, an unsurprising fact when we take into account the (Western) literary canon’s inherent whiteness and maleness, as well as the institutional history of English departments as tools of the colonial project — teaching works of English literature in the British Empire’s overseas colonies was originally part of the overarching goal of “civilising the natives.” In the words of 19th century British politician Thomas Macaulay, “a single shelf of a good European library is worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia” (gotta love that British sense of entitlement and arrogance).

In any case, amidst the steady diet of Shakespeare and Dickens in school, encountering Hossain’s delightful story, which I promptly borrowed from my professor, blew my mind wide open. Sultana’s Dreamis a futuristic tale in which the concept of the upper-caste Indian Muslim notion of the zenana (seclusion of women within a specific section of the house) is flipped to imagine a utopian world where men are sequestered into the mardana while South Asian women smoothly and efficiently run society through scientific innovation and reason.

The exploration of domesticity, gender and the notion of public and private space situated within 20th century colonial Indian nationalist and gender politics using science fiction tropes and an archly playful tone — I had never read anything like it before. If Hossain’s story was different from those of the white, male authors that populated my course syllabi, it was also distinct from the kind of realist South Asian fiction that is usually privileged as “literary” and therefore more worthy of attention or academic study.

At that time, there was a certain kind of post-9/11 Anglophone Pakistani fiction that you were supposed to be reading: the kind that used a specific style of grim realism to explain South Asian “issues” like terrorism, poverty or corruption. Playful, experimental, speculative works like Hossain’s or those of her more contemporary counterparts, either in English or local languages, rarely come into the discussion.

This dismissal of the genres of science fiction and fantasy (SFF) as low-brow, trashy or pulp or, at the very least, unimportant, is not just a desi stance, although it might be a bit more pronounced here. The snobbish attitude towards SFF has historically been prevalent in academic and literary circles (although things seem to be changing in the West now), even as popular culture is filled with beloved works of science fiction and fantasy films and television shows.

But the dismissal of the SFF genre, or the broader umbrella of speculative fiction, has excluded from the South Asian literary discourse a rich tradition of desi works of science fiction and fantasy, as well as the fascinating speculative fiction words being written by contemporary South Asian writers today. This makes conversations about South Asian literature woefully homogenous and, frankly, much more uninteresting than they might otherwise be.

I.

Even though definitions are notoriously slippery things in literary criticism, we might define SFF as a broad literary genre encompassing any fiction with supernatural, fantastical or futuristic elements.

Ursula K. Le Guin, one of my favourite SFF writers, explains it this way:

“All fiction is metaphor. Science fiction is metaphor. What sets it apart from older forms of fiction seems to be its use of new metaphors, drawn from certain great dominants of our contemporary life – science, all the sciences, and technology, and the relativistic and the historical outlook, among them. Space travel is one of these metaphors; so is an alternative society, an alternative biology; the future is another.”

Closer to home, Pakistani sci-fi, fantasy and horror writer Usman T. Malik defines it as:

“the literature that explores the boundaries of knowledge… that definition is mostly applicable to speculative fiction’s subgenres, including magical realism, fantasy and horror; it’s just the class of knowledge that changes within each.”

Given these definitions, works of South Asian science fiction and fantasy have existed long before both genres came to be codified as such.

Whereas “science fiction” as a distinct, recognisable genre term only came together in the early 20th century and “fantasy” a few decades after that, works that utilise SFF conventions and tropes have existed since long before. As Dalit speculative fiction writer and editor Mimi Mondal explains in her two-part history of South Asian speculative fiction, the earliest works of speculative fiction in the subcontinent were written in Bengali, Tamil and Urdu in the mid-19th century, published from Calcutta, Madras and Lucknow respectively (although oral stories go back even further).

The earliest subgenres to gain popularity were horror, crime and detective stories, all with a bent towards the fantastical, told in a folkloric style. There is, of course, the Dastan-e-Amir Hamza, adapted from the oral dastan into written Urdu by Ghalib Lakhnavi in 1885, or its literary successor, the Tilism-e-Hoshruba, written by Muhammad Husain Jah in 1883. Both works are brimming with magic and the fantastical, jinns and paris, trickster ayyars and parallel magical universes called tilisms, centuries-old prophecies and classic good vs evil battle scenes (not to mention some very unfortunately regressive and troubling gender politics, conveniently ignored by most Urdu literary critics).

In a similar vein was Chandrakanta (1888), the Hindi fantasy epic by Devaki Nandan Khatri equally filled with ayyars and tilisms, which gained a cult following and was turned into a massively popular Indian serial in the 1990s. In Bengali, Rabindranath Tagore wrote supernatural horror stories, while Jagadish Chandra Bose, a biophysicist wrote the earliest science fiction of the language, including his short story ‘Niruddesher Kahini’, which was published in 1896.

There was also Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, my literary favourite of the period, an upper-caste Muslim woman, a political activist, educationist and feminist thinker who struggled for the rights of women and critiqued the 19th century notions of purdah from within, through science fiction, writing in both Bengali and English.

In the post-independence period, the literary cultures of Bengali and Urdu became split across two (and, eventually, three) countries, and pretty much stopped being in conversation with each other but continued to grow separately, each producing various forms of SFF.

The Urdu series that I grew up hearing about, as part of our family lore, was the popular supernatural spy thriller Imran, a series that began in 1955, written by Ibn-e-Safi and later taken over by Mazhar Kaleem in the 1970s. According to my mother, she and her brothers and sisters would eagerly wait each month for the latest issue chronicling the adventures of the dapper and brilliant secret agent/detective to come out, and then squabble over who got to read it first.

There was also Kala Jadoo, a horror/dark fantasy novel by M. A. Rahat, who wrote prolifically in the SFF sub-genres of horror and mystery, which were published in various digests and periodicals across Pakistan from the 1960s onwards. Another popular work was Devta, a serialised fantasy thriller novel by Mohiuddin Nawab, written in the form of an autobiography of a man with telepathic powers, which was published in the Karachi-run Suspense Digest for 33 years from 1977, making it the longest continuously-published series on record.

In 1950, Urdu humourist and writer Mohammad Khalid Akhtar wrote Bees Sau Gyara, a satirical dystopian novel in the vein of Orwell’s 1984, creating a futuristic world in which the poor and homeless are re-named Lovers of the Open Air, a special police category is PULJAKMACH — Pakar Lo Jis Ko Marzi Chahey and the state machinery includes the Ministry of Lies, the Ministry of Ignorance and the Ministry of Food, which are all operated by the identical twin brother of the Minister of Finance.

SFF in Bengali flourished to an even greater degree. As Mondal explains:

“As science fiction became more distinctly recognizable as a genre in the West through the twentieth century, the language that most directly caught the influence was Bengali. Every prominent Bengali author has written speculative fiction in some parts of their career — stories that are widely read, loved, and often included in school syllabi — since the speculative imagination is inseparable from realism in the Bengali literary culture.”

These Bengali writers include the great Satyajit Ray, India’s most famous and prolific SFF writer, although he is known more as a filmmaker outside India. He wrote, among other SFF works, the Professor Shonku series from 1965, about a scientist and inventor who solves mysteries in both real and fantastical lands, a kind of supernatural, Bengali Sherlock Holmes (incidentally, Ray based Professor Shonku partly on a character of Arthur Conan Doyle).

Clearly, there is a rich tradition of SFF fiction in the subcontinent, in various languages, dating back to at least the 19th century, which uses culturally grounded fantasy tropes, such as ayyars, paris and jinns, as well as sci-fi tropes of technology, scientific progress and invention to tell stories of horror, intrigue and humour and which comment on or reflect, in interesting ways, the culture, history and politics of South Asia at various moments in its history.

A survey of South Asian literature which excludes such a diverse and fascinating body of work, merely by virtue of it being “low-brow” or pulp, is therefore not just incomplete, but also much less varied and certainly much less fun.

II.

When I was growing up, my English-medium education and access to cheap second-hand American and British paperback novels meant that I mostly read about the adventures (both fantastical and realist) of white kids and teens, with only a smattering of Urdu children’s novels of horror, adventure and humour about characters who looked like me.

The whitewashing of the stories I read in English as a child is indicative of a structural problem, one that includes the whiteness and maleness of the literary canon, and also the racial and gendered gatekeeping of the Western publishing industry, all of which affects the kind of books that circulate in the global literary marketplace, and therefore reached me in Karachi as I was growing up.

But with Western speculative fiction, particularly science fiction, there is an additional wrinkle. Literary scholars have pointed out that the rise of science fiction as a genre occurred at the height of Western imperialism, making the origins of sci-fi complicit with colonialism and its ideologies.

According to scholar Adam Roberts, science fiction serves as the “dark subconscious to the thinking mind of Imperialism,” the seedy underbelly hidden beneath the rationalistic veneer given to colonial and neocolonial ideas. After all, the two biggest myths in science fiction are that of the Stranger and the Strange Land. “Stranger” (the alien, whether it’s extraterrestrial, the technological, the human-hybrid) and the “Strange Land” (the far away planet waiting to be conquered).

In her book Postcolonialism and Science Fiction, Jessica Langer argues that these two myths of science fiction are also the twin pillars of colonialism: the Stranger is the Other (the savages whose lives and behaviours are strange, whose cultures are misshapen but who nevertheless retain an exotic fascination because of this strangeness) and the Strange Land that these Others occupy, and which are in need to “settling” and “civilising”. These myths are at the heart of the colonial project as well.

A lot of the science fiction written in the 19th and 20th centuries in the West explored — and in many instances, reinforced — these colonial myths in various forms. Many of these SFF works, for example, flip the racial dynamic that characterised the most influential imperialist ventures of the last few centuries. In such stories, the conflict is about “them” (a non-white, foreign civilisation) doing to us (Western, largely white powers) as we did to them.

But just as the genre of science fiction has been a vehicle to explore and further imperial fantasies, it also developed into a genre through which critiques of colonialism and racism could be enacted, through which non-white people, with their violent histories of colonialism and slavery, could tell their own stories, drawing on their own cultural heritages in different forms.

Afrofuturism, for example, is a vast subgenre of SFF which treats African-American themes and concerns, and Black history and politics, through the motifs, tropes and imagery of science fiction and fantasy. Marvel’s Black Panther is a recent, popular example of the subgenre, but Afrofuturist works, by Black writers such as Octavia Butler and Robert Delaney, have been around since the 1960s.

Similarly, since the 1980s, as English became the more common language for SFF in South Asia, overtaking or at least catching up to genre fiction in Urdu, Bengali and other languages, South Asian speculative fiction writers began using the genre to engage with the violent colonial legacy of the subcontinent using the motifs and tropes of SFF. Their works can be said to be part of what is a nascent sub-genre known as postcolonial science fiction.

An early example is Amitav Ghosh’s The Calcutta Chromosome, published in 1995. His only foray into speculative fiction, Ghosh’s completely bonkers (in the best way) novel juggles multiple timelines, one in 19th century colonial Bengal, one in 1990s Calcutta and one far into the future in New York. It explores themes of colonialism, marginality and notions of Western versus indigenous forms of knowledge and medicine, using common sci-fi tropes of cyborgs, artificial intelligence and surveillance technology.

Other Indian writers such as Samit Basu (whose 2004 Gameworld trilogy is pitched as “Monty Python meets the Ramayana and Robin Hood meets The Arabian Nights“) and Khuzali Manickavel (whose short stories combine SFF with a distinct Tamil English sensibility) started emerging, whose work found an audience with a new generation of SFF fans who read primarily in English.

This new generation of South Asian SFF writers, who are writing in English and are more explicitly in conversation with Western science fiction and fantasy, are doing really fascinating things in their work. They are doing this by appropriating, remixing and upending Western SFF tropes to explore concerns that are firmly situated within South Asian history, culture and politics, using imagery and motifs that are distinctly desi.

For example, as I have written elsewhere, many contemporary writers are re-appropriating the mythological figure of the jinn (appropriated and tamed into the benign figure of the ‘genie’ by Orientalism writers of the 19th and 20th centuries) to talk about contemporary South Asian concerns.

One of my favourite stories in this vein is ‘Bring Your Own Spoon’, a short story by Bangladeshi SFF writer Saad Hossain, published in an excellent anthology edited by Mahvesh Murad and Jared Shurin called The Djinn Falls in Love. The story is set in a futuristic, dystopian Dhaka ravaged by climate change, a world where the boundary between the human and superhuman worlds has become threadbare because of a collective struggle for survival.

In this city, where the bodies of the poorest, most marginalised in the society are used by nanobots to clean the air for the rich, a jinn and a human decide to open a restaurant together, allowing people on the fringes of this society to come together as a community through food and the memory of a better past.

With masterfully done worldbuilding and brimming with hope (very hard to pull off in a dystopian narrative), Hossain uses a distinctly desi mythological figure to comment on the unique ways in which climate change and capitalism are affecting contemporary South Asian society.

Other SFF writers, including Pakistani ones, are doing similar things — mixing a distinctly desi sensibility with science, technology and myth to produce stylistic varied and interesting stories. There is Usman T. Malik, who has combined Sufi philosophy, South Asian history, with cosmology and physics to explore things such as terrorism, gendered violence and feudalism in his short fiction, published in various anthologies and online SFF magazines (his story ‘The Vaporization Enthalpy of a Peculiar Pakistani Family’ won the Bram Stoker Award in 2014).

There is Sami Shah, who has his own spin on the jinn in his Boy of Fire and Earth, and whose contribution in Murad’s anthology, ‘Reap’, also used desi horror tropes of jinn and possession to make a masterful commentary on drone strikes and US imperialism.

Shazaf Fatima Haider and Bina Shah have both recently entered into the foray of speculative fiction, with a supernatural young adult novel (Firefly in the Dark) and a feminist dysoptian novel respectively (Before She Sleeps), articulating, in their own ways, concerns about gender, sexuality and coming-of-age which feel both distinctly South Asian and universal.

The best of South Asian SFF is that which casts in a new light our turbulent history to imagine different presents and futures. For example, Indian writer Vandana Singh’s short story ‘A Handful of Rice’ takes place in an alternate part of South Asian history where the Mughal Empire gave way not to the British Empire, but an era of a syncretic empire with technological advances and steampunk wonders.

Sri Lankan writer Yudhanjaya Wijeratne’s ongoing trilogy, The Commonwealth Empire, imagines Kandy in an alternate future in which the British Empire never fell but remained strong through advanced technology.

Mary Anne Mohranraj, another Sri Lankan writer (this one from the diaspora), wrote a delightful novella The Stars Change, set on a technologically-advanced distant planet colonised by South Asian people, which playfully explores gender, sexuality and intimacy against the backdrop of colonialism, caste and race.

Another particularly compelling example is Indian writer Prayaag Akbar’s novel Leila (published in 2017, recently turned into a Netflix TV show helmed by Deepa Mehta), set in a futuristic Indian city which, due to a scarcity of water and the rise of religious authoritarianism, is segregated into sectors based on caste and religion.

In this digitised, highly surveilled city, each sector is surrounded by 60-foot walls and “purity,” both in terms of caste and class, as well as in the physical terms of air and water, dictates social hierarchies. It’s not hard to see the resonances of contemporary India in Akbar’s novel, and its critique of class and caste has many uncomfortable parallels with Pakistani society as well.

South Asian SFF, in various languages and across very distinct moments of the subcontinent’s history, has always found imaginative and refreshing ways to look at the world at large and South Asian society in particular. The best of it evokes in us a sense of awe, and also a sense of vulnerable humanity — the kind of literature that allows you to look at our world’s wonders with delight and its stark and complicated political and social realities with clear and focused eyes.

Contrary to popular belief, speculative fiction is not necessarily escapist — as the best South Asian SFF writers have shown, it is that which brings us closer to our own reality, which presses our faces up against our society, warts and all.