September 19, 2022

JAKARTA – For more than a decade the basement of Blok M Square – one of South Jakarta’s most popular shopping malls – has been home to dozens of bookstores selling new, secondhand and out-of-print books of all kinds and subjects imaginable, a heaven for booklovers in the capital city and its surrounding regions.

However, the increasing popularity of e-books and audiobooks and the economic blow brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic has left these establishments shells of their former glory.

Unlike the clothing, jewelry and food stores in the upper floors that are jam-packed with crowds and bustling with transactions, customers rarely venture to the lowest floor of the shopping mall. Many kiosks have closed their doors permanently, leaving behind piles of dusty old books covered in tarp in front of their stores.

Umar Wirahadi Kusuma, owner of the Papat Limo bookstore, which first opened in 2010, said that his revenue had dropped by around 70 percent in the last decade.

“Indonesians in general have very low interest in reading books. Now with gadgets and everything, their reading interest has gone down further,” Umar told The Jakarta Post recently. “Only hardcore booklovers visit my bookstore now, and they amount to less than 0.1 percent of Jakarta’s population.”

Another bookstore owner, Wiwik Latifah, who sells new, secondhand and rare books, shared a similar experience, saying that revenue had dropped by 50-70 percent, especially after the pandemic hit.

“When I first opened my store, Ziarah Buku, in 2009, I could earn revenue of around Rp 30-35 million a month. Nowadays it’s difficult to even reach Rp 10 million in any given month. On average we only have one or two visitors a day, and sometimes none at all,” she said.

According to Wiwik, her store’s current revenue is barely enough to cover overheads such as electricity for her five kiosks, each of which costs around Rp 1 million per month.

Wiwik said that many bookstores in the Blok M Square basement were unable to keep up with rising operational costs and drops in sales, leading to almost half of the businesses folding for good in the past couple of years.

The gradual decline in book sales, she added, was the result of the public’s shifting preference from reading physical books to reading e-books or listening to audiobooks. The trend was exacerbated by the speedy growth of digitalization during the pandemic, which forced people to stay home and led to the popularity of reading apps and online learning materials.

“Buying physical books is more costly and takes more time than purchasing e-books on your phone. Making the situation worse, the pandemic has not only reduced people’s purchasing power, but also sped up digitalization,” Wiwik said.

“Usually a lot of people buy school textbooks at the beginning of the school year, but since classes were moved online during the pandemic, with online lessons and materials, there are fewer parents wanting to buy physical textbooks for their kids,” she added.

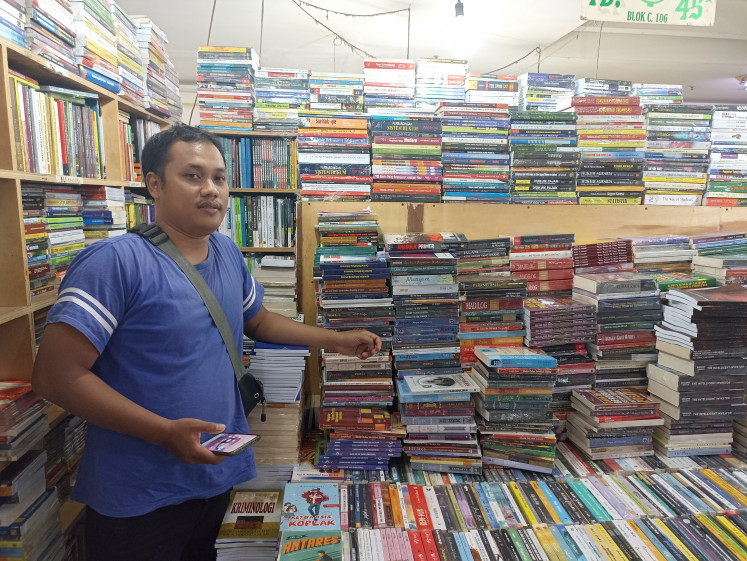

Umar Wirahadi Kusuma, owner of the Papat Limo bookstore in Blok M Square mall, South Jakarta, poses among piles of secondhand books on Sept. 8, 2022. Umar says that his revenue has dropped by around 70 percent over the last decade. (JP/Nina A. Loasana)

Online market

Although technology has been singled out as one of the biggest causes of disruption for the likes of Umar and Wiwik, it has ironically helped keep their bookstores afloat.

Umar said that the only reason he was still able to open his bookstore at Blok M square was online book sales.

“I’ve been selling my books online for the past six years, and although the competition is tough, I can reach a wider market compared with only opening a physical bookstore,” he said. “Since 2016, my online book sales revenue has grown roughly 10 percent every year.”

Wiwik said that although her online book business had helped Ziarah Buku bookstore to keep going, it was not enough to bounce back to the glory days of the bookstore.

“There is a lot of competition online. There are also a lot of merchants who sell pirated books, which are much cheaper compared with original or second hand ones. Sometimes customers cannot tell the difference, so they often choose to buy the cheaper ones,” she said.

Bookshop owner Wiwik Latifah, who sells new, secondhand and rare books, poses in front of cupboards full of books in her shop in Blok M Square mall, South Jakarta on Sept. 8, 2022. Wiwik said her revenue from selling books has dropped by 50-70 percent, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. (JP/Nina A. Loasana)

Jakarta Literacy

Over the past few years, the Jakarta administration has championed improving citizens’ literacy levels as one of its main programs. City officials have revamped several public libraries in the capital city and provided books in many locations in public places to be read on-site.

Jakarta is home to more than 5,000 libraries and 1,000 publishing houses, as well as nearly a third of all modern bookshops in the entire country, according to one industry estimate. Every year, the publishing industry produces around 120,000 titles from some 5,000 publishers nationwide, making Indonesia one of the largest producers of books in all of Southeast Asia.

Last year, UNESCO awarded Jakarta the title of City of Literature alongside 40 other cities from 29 countries, placing it in the United Nations agency’s Creative Cities Network that recognizes creativity as a major factor in urban development.

Despite the prestigious title however, writers, publishers and bookstore owners say that the city is still struggling to maintain a sustainable literary ecosystem.

Booksellers in Blok M square are not the only ones hit particularly hard by the pandemic. Similar businesses in Pasar Kenari – established by Governor Anies Baswedan in 2019 – and on the renowned Jl. Kwitang in Central Jakarta are also struggling to survive the pandemic, with many ending up closing their businesses for good.