December 22, 2022

BEIJING – Zang Chaiyuan has recently been working deep into the night as people are lined up for her steamed buns. The 25-year-old from Yantai, East China’s Shandong province, has managed to turn flour into a gold mine through her ingenious maneuvers that breathe modern elements into “Jiaodong huabobo”, a popular traditional food dating back more than 300 years, especially in the province’s Jiaodong peninsula.

Huabobo refers to a flower-shaped steamed bun, which has been a treat at local folk activities, such as celebrations and festivals.

It was listed as a provincial intangible cultural heritage in Shandong in 2009.

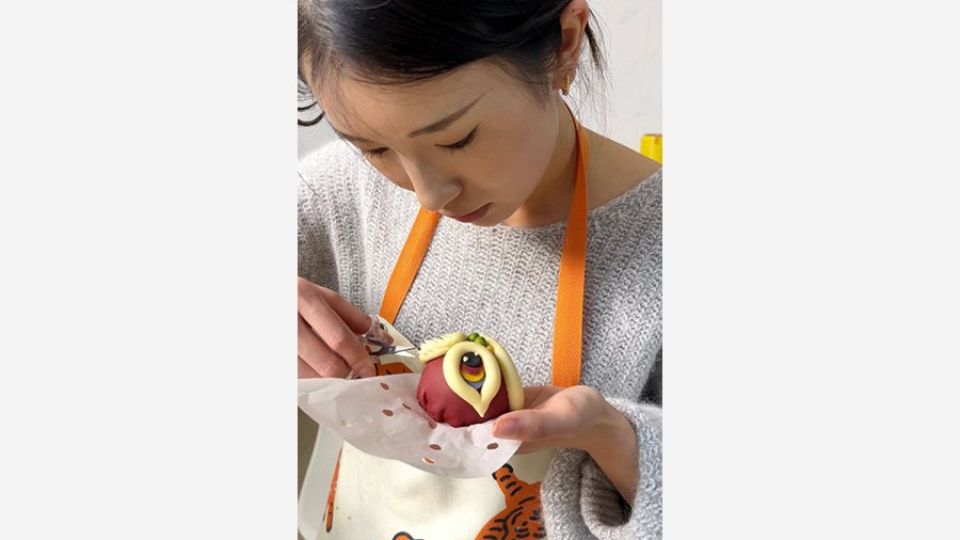

The buns are shaped by Zang’s adept hands. These shapes range from cute rabbits dressed in lion dance costumes to treasure bowls and lucky bags, among others.

They have made her an online sensation and ignited a media frenzy that has earned her approximately 100 million views on multiple platforms, including Douyin and Sina Weibo.

“It’s the details that matter,” Zang says about the popularity of her buns.

As demonstrated in one of her videos, she took pains to create a red-flour layer to dress up her rabbit and meticulously sculpt its facial features and fur.

“I also made a point of highlighting the cuffs,” she says.

As the flour swells in the steamer, the rabbit seems to take on a life of its own.

The corners of its mouth turn upward, and its skin springs back perfectly when Zang’s fingers press it.

Many of her followers have made purchase inquiries for her buns and commented that they are too cute to be eaten.

“The New Year holiday is coming, and we’re snowed under with orders,” Zang says.

Zang found her opportunity when she noticed that most of huabobo shops were running the old-fashioned way. “Their customers are basically people in the neighborhood,” Zang says.

“Although the buns taste good, the sales channels are quite limited,” she says, adding that the buns can be preserved for more than two months in a freezer, which makes long-distance sales possible.

That was when she figured if she could move the intangible cultural heritage online to expand its sales and boost its popularity.

However, it was not plain sailing at the beginning.

Her parents initially opposed her decision to open a huabobo shop.

“They believed young people should find a steady job, like being a civil servant or a teacher,” Zang recalls, adding that they also thought bun making was better for more elderly women.

However, she stood her ground.

A set of Zang’s works that depicts various cute rabbits dressed in lion dance costumes and other auspicious outfits.[Photo provided to China Daily]

“I tried before, working at a hospital or a shopping mall,” she says.

“They confirmed my belief that it has to be something that I like before I can make a go of it.”

Zang then set her sights on huabobo at the beginning of 2020.

“I found huabobo was the norm for birthdays of local children and elderly people and there was a great demand for them, thus making it a good business choice,” she says.

Besides, she loved huabobo in her childhood.

“My grandmother used to make me huabobo, in all kinds of shapes, which were very beautiful,” Zang recalls.

“She would also give me a dough and teach me how to make animals as toys,” she says, adding that her grandmother always told her they should not only look good and taste delicious, but be healthy.

The flour bun has evolved into an indispensable part of major occasions, such as weddings, birthdays and holidays.

Local women use knives, scissors, nippers, and combs to make auspicious figures such as duck, gourd, dragon, phoenix and peach with fermented flour, before having them steamed. Their beautiful and bright colors are generally considered to convey blessings, peace, longevity and prosperity.

A set of Zang’s works that depicts various cute rabbits dressed in lion dance costumes and other auspicious outfits.[Photo provided to China Daily]

“Knives, scissors and pens are usually involved in the creation,” Jia adds.

Zang first learned, from an experienced huabobo master, the basic skills and then practiced over and again on her own.

“It was frustrating at the beginning, when the buns were often cracked after being steamed,” Zang says.

“How to concoct the dough and take care of its fermentation is the key, and it needs trial and error to get the best results,” she adds.

She also extracts natural fruit and vegetable juice, such as that of spinach, pumpkin and butterfly peas, to color the flour.

“Then, there is milk, eggs and a bit of sugar, nothing else,” she says.

It didn’t take long before Zang got the whole process down to a fine art, literally.

With a little more than 10,000 yuan ($1,437) of her own savings, Zang opened her first small huabobo shop in Yantai.

Seeing her commitment, her family no longer stood in her way, and even came to help.

The cute flour figures soon appealed to an increasing number of customers, especially of her generation.

A set of Zang’s works that depicts various cute rabbits dressed in lion dance costumes and other auspicious outfits.[Photo provided to China Daily]

As her skills increased, sales in her brick-and-mortar shops and online orders have both been on the rise, including those from the 50,000 fans on her social media accounts, such as Douyin. The brisk sales have seen her open a second shop in downtown Yantai in October and hire eight employees.

“We have received about 30 to 40 orders a day; each order is for buns of about two to three kilograms and is worth around 300 yuan,” Zang says.

Her products have also made their way to customers from the major cities, including Beijing, Shanghai and Zhejiang province’s capital Hangzhou.

Ever since she became an online phenomenon, Zang has also been confronted with accusations that it’s a waste of her college education to make buns.

She thinks there’s no hierarchy in careers.

“As long as I get to do what I want and make something of it, it will be worth it,” she says.

She also believes that young people should think outside the box and try more things, like traditional crafts, which “need young people to carry forward”.

Zang has held training sessions at her shops and shot a video for those who live far away.

“Many have shown great interest in picking up huabobo skills, especially women who have just become mothers,” she says, adding that she is glad that more young people have engaged in the traditional craft.

“Some of them have already opened their own shops.”

As her popularity grows, Zang says she feels more pressure.

“It has prompted me to make huabobo more exquisite,” she says.

Speaking about her plans, Zang says she wants to apply her financial background to her business venture.

She would like to standardize production and form a complete supply chain for huabobo.

“Now that my grandmother is gone, I want to make this passion my career and keep on doing it,” Zang says. “I also love traditional Chinese culture and believe that the craft of making huabobo is worth promoting.”