March 1, 2023

DHAKA – Over the years, alongside sustained economic growth, Bangladesh has made remarkable strides in reducing poverty. The international poverty line is set at $2.15 per person per day based on 2017 prices. This means that anyone living on less than $2.15 a day is in extreme poverty. Based on the World Bank report titled Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2018, the poverty line rate in Bangladesh decreased to 20.5 percent, while the below-poverty line rate decreased to 13.8 percent. Hence, life expectancy, literacy rates, and per capita food production have all concurrently increased.

The Bangladesh government has set different milestones for the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. In its 8th Five-Year Plan (8FYP), the government has targeted an eight percent average growth rate during the July 2020-June 2025 period, set the goal to reduce the poverty rate from 20.5 percent to 15.6 percent, and aims to further strengthen the existing social security system while eliminating poverty and narrowing inequality. Furthermore, it plans to increase public spending in healthcare from one percent to two percent of the GDP. The Perspective Plan (2021–2041), released in 2020, outlines the government’s goal of bringing down poverty to less than three percent and its vision to achieve a “Smart Bangladesh” by 2041.

Despite these achievements, the Covid-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, the consequent price hikes and the global economic crisis have impeded the progress towards these goals. Moreover, the head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned that a third of the global economy will be in recession this year.

Due to the pandemic and the new socioeconomic crisis, the poverty rate almost doubled from 20.5 percent in 2018 to 42 percent in 2022, while the below poverty rate tripled from 13.8 percent to 28.5 percent. The rate tripled in both rural (33 percent) and urban (19 percent) areas compared to their respective rates in 2018, which also had a spillover effect on healthcare. The poor and disadvantaged have faced additional medical costs, poor management and negligence of healthcare facilities, which paint a bleak picture of the overall healthcare landscape of the country.

Additionally, most of the poor suffer from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD). With the disadvantaged already suffering from economic vulnerabilities, the additional economic burden of having to avail medical treatment led to a crisis of catastrophic proportion. In recent years, the percentage of out-of-pocket expenditure (OOP) in healthcare has increased to about 73 percent from 67 percent. This indicates that they are mostly taking medical treatment from village or local quacks or pharmacies. More often than not, they consume an excessive amount of antibiotics, which invariably leads to antibiotic resistance.

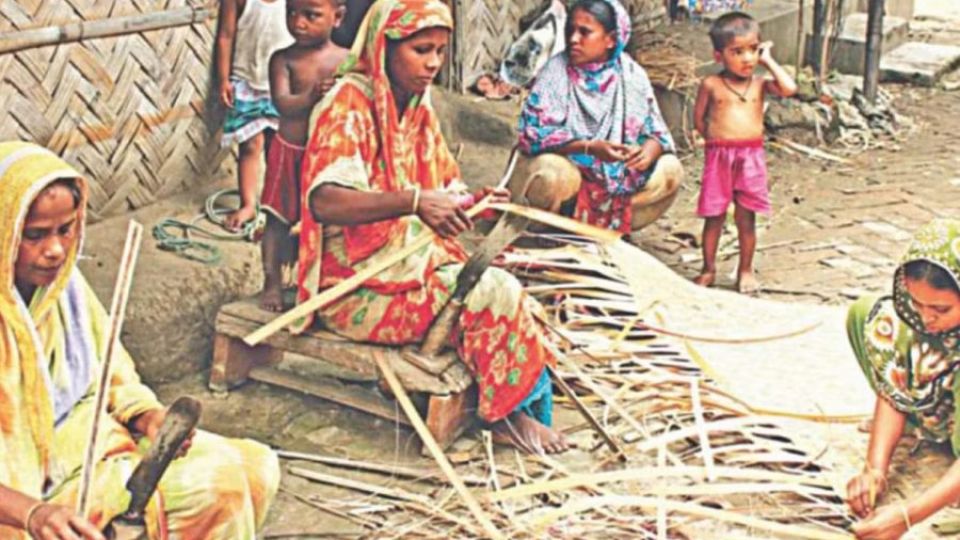

This paints a truly concerning portrait of the dual stresses afflicting the poor – financial and healthcare – brought on by the pandemic and the new socio-economic crisis. This has led to the creation of a new group called the “new poor.” Presently, their existing coping mechanisms against this new crisis include selling off their assets, working extra hours, dipping into their savings, and taking on the burden of debts. Failure to manage the basic necessities for survival has driven numerous poor families to leave the capital city and other urban areas and relocate to their village homes.

Most of these people also remain poorly underserved by government services. Lack of livelihood skills and training, educational opportunities, inadequate and/or poor quality health and nutrition services all impose multiple burdens on the population that are already at or below the poverty line, and keep them trapped in the vicious cycle of poverty.

To mitigate this situation, the government and policymakers are trying to explore and implement new paths and strategies to improve the lives, livelihoods and healthcare of this vulnerable segment of population. Despite some laudable government efforts, non-government organisations (NGOs) and the private sector actors need to be called on for short-to-mid-term solutions, approaches and strategies with integrated interventions.

Increasing social safety net coverage and ensuring accessibility to the poor via service linkage would be a good start to this end. Equally critical are incentivising and providing opportunities for savings, disseminating direct grants or asset transfers, disbursing soft or interest-free loans to create new employment opportunities or facilitate recovery of existing livelihoods, and creating avenues to build livelihood skills. Furthermore, assuring holistic healthcare solutions, providing community-level healthcare, and adopting initiatives to ensure access to affordable, quality healthcare and reducing OOP expenditures will all play vital roles.

These integrated initiatives could facilitate quick recovery of the poor, not only enabling them to develop safety nets against current and upcoming socioeconomic crises, but also helping them achieve economic resilience, receive adequate health coverage, and lead improved lives.