March 30, 2023

SEOUL – In 1977, a little over two decades after the war that hardened the division of the peninsula ended, South Korea celebrated an economic milestone with much fanfare: $10 billion in yearly export volume.

It had been just a year since the country had stopped receiving US aid worth a colossal $12.6 billion from 1946 through 1976, which helped rebuild most modern infrastructure there had been before the war.

The Dec. 22, 1977 edition of The Korea Herald celebrates the “$10 billion export fete” with an article in the middle of the page. (The Korea Herald)

“Our achievement of $10 billion in exports has a bigger meaning than just its size in terms of the fact that it was an opportunity for us to showcase our infinite power and potential,” then-President Park Chung-hee lauded the figure during the 14th Export Day event held Dec. 22, 1977 in Seoul. Renamed Trade Day, the annual event honoring the country’s accomplishment with oversea markets continues to this day.

The leader praised Korea’s achievement in reaching the $10 billion mark in just six years since the goal was set out in 1971, half a decade earlier than he had initially expected.

“It took West Germany 11 years to grow from $1 billion to $10 billion, and Japan 16 years to do the same,” he added.

In the Dec. 22, 1977 edition, The Korea Herald published two articles that captured the buoyant mood, ambitious aspirations and self-reinforcing confidence of a country that was starting to bring about what would later be recorded as the “Miracle on the Han River.”

The article titled “ROK exports to reach $110 billion by 91” cited the projection made by the then-military junta government that the country’s exports would reach $110 billion — 11 times the 1977 level — within a decade and a half.

“Korea will be listed in the front rank of exporting countries in 1991 with its annual export volume reaching $110 billion and per capita GNP income passing the $3,000 mark,” the article read.

Outbound shipments hit $100 billion in 1995, somewhat later than the ambitious time frame set by the Park regime, but it has continued on an upward trajectory to reach $683.9 billion as of the end of last year, its largest figure ever.

As for the per-capita gross national product target, it is easier to look at gross domestic product data, which is a similar but more widely used measure of an economy’s size.

The per capita GDP of South Korea was around $64 in 1953, when the Korean War ended. It now stands at around $32,000, as of last year.

“One way to think of Korean economic miracle is that it’s the best example we have about how the market system worked in a country (which) previously was quite poor, and in one lifetime, people achieve standards of living comparable to high income countries,” comments Jeffrey Frankel, a professor of capital formation and growth at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, on a KBS TV documentary on the Korean economy from 1999, which is now part of the collection of the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History.

“There are other examples, but maybe Korea is the best example,” he said.

Precious dollars

How could a country poor in natural resources with virtually no modern industries become rich? That was the main question that postwar South Korea had to tackle.

Over time, Korea’s economic policymakers came to the realization that exports were the key.

The $10 billion export milestone, achieved in 1977, came along this journey of Korea’s transformation from rags to riches, driven mainly by at first selling simple processed goods in overseas markets.

In the 1960s, the main export items were tinned iron, plywood, textiles and wigs.

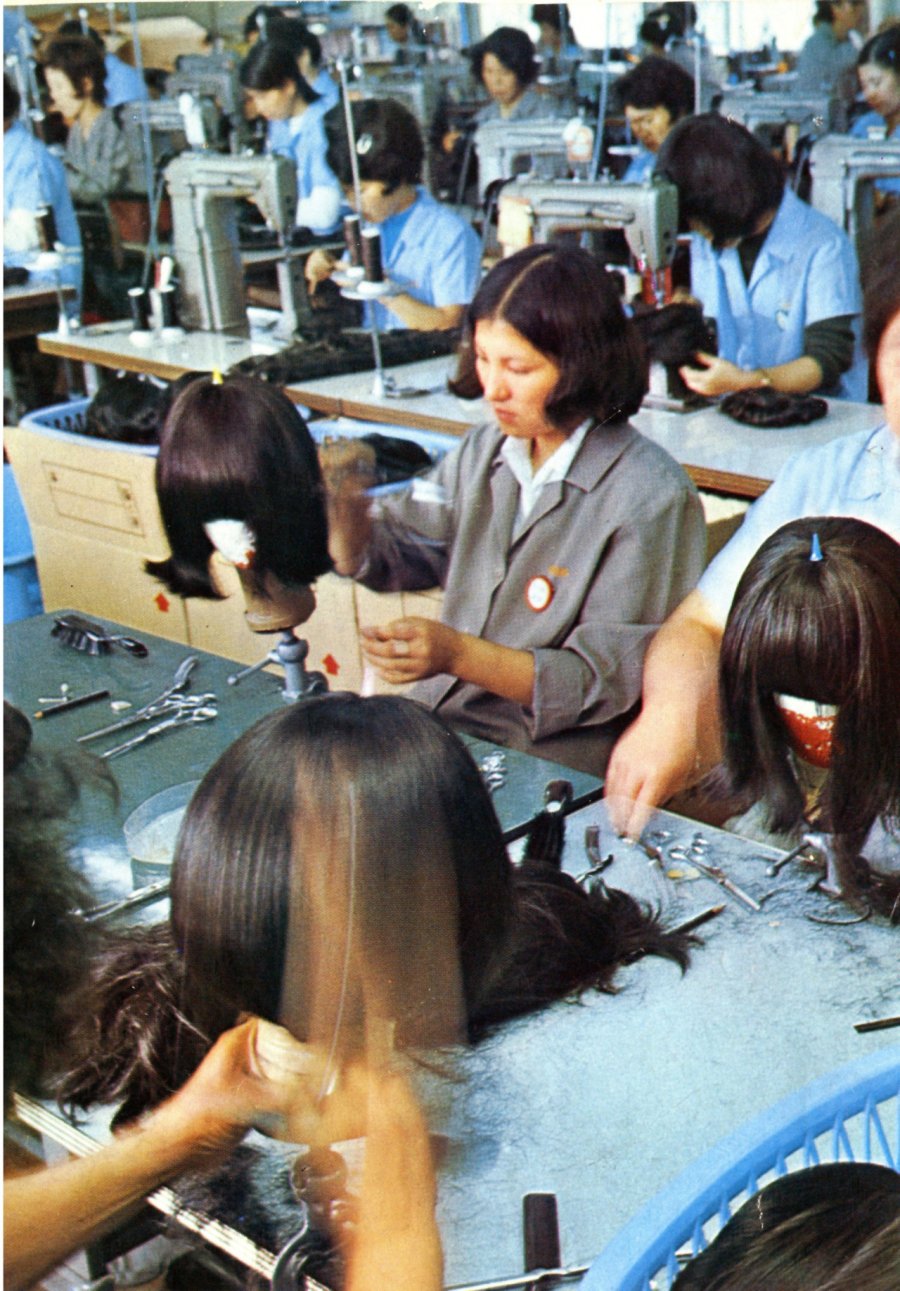

Guro-gu in Seoul emerged as a factory town for export items such as textiles and wigs, attracting women workers who were undereducated, but hard-working and dexterous.

In the following decade, South Korea’s focus shifted to heavy industries and more sophisticated products, such as electronics, petrochemicals, steel and ships. The construction industry experienced a surge in demand from overseas, particularly from the Middle East, due to South Korea’s reputation for efficient and cost-effective labor. The country also added automobiles to its list of exports during this decade.

The Park regime, which rose to power via a military coup in 1961 and continued until his assassination in 1979, paid a great deal of attention to exporters. Each month beginning in February 1965, the regime held a regular meeting on exporting affairs, inviting various related representatives to check on anything hindering Korean businesses overseas. Most of the meetings were presided over by Park himself.

“Under the military government of Park Chung-hee, which came to power in 1961, the state gave priority to economic development, focusing on a combination of state planning and private entrepreneurship,” read a 2017 report published by Michael J. Seth, a history professor at James Madison University.

“Possessing few natural resources, it depended on a low-wage, educated and disciplined labor force to produce goods for exports. As wages rose, economic development shifted from labor to capital-intensive industries,” it added.

With the rapid growth of exports, conglomerates such as Samsung and Hyundai began to gain more clout as well, playing a large role in the country’s manufacturing and outbound shipments.

Korea saw record-high rates of gross domestic product growth from 1986 to 1988 especially, bolstered by its surge in exports. Its annual growth came to an average 12 percent in the cited years, which was one of the highest in the world at the time. The 1987 June Democracy Movement — which brought an end to nearly three decades of military rule here — further fueled outbound shipments.

World-class brands and new challenges

Today, tiny semiconductor chips — the brains inside almost every gadget from cars and phones to medical devices – represent the new face of Korean exports. In addition, cultural products, such as Korean TV dramas, K-pop songs and films, are rising as a new lucrative export sector.

This undated file photo shows workers at a wig factory, which was a major export item for South Korea in the 1960s. (The Korea Herald)

“Textile exports declined in relative terms in the 1980s, replaced by consumer electronics, computers and semi-conductors as lead exports. In 1983, the first Hyundai cars were exported,” the report by Seth showed. “By then, the country had become one of the largest shipbuilders and steel exporters in the world.”

The overseas market for K-pop roughly doubled from $5.7 billion in 2015 to $10 billion in 2019, according to the Diplomat last year. The country’s exports of K-pop albums saw a fresh high of $223.11 million last year, up 5.6 percent on-year, data provided by the Korea Customs Service showed.

Outbound shipments of memory chips came to a record-high of $129.2 billion as of the end of last year, inching up 1 percent on-year, amid a recovery in the global chips industry, according to the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy. Semiconductors accounted for about 20 percent of total exports by South Korea last year. The industry is spearheaded by chip giants Samsung Electronics and SK hynix.

Korea is now the world’s sixth-largest exporter, behind China, the US, Germany, the Netherlands and Japan.

Despite the accolades, Korea faces new hurdles as a world-class exporter. Its dependence on overseas market as an export-oriented economy has made it excessively vulnerable to overseas risks, critics point out.

A September 2022 report published by global think tank Economist Intelligence highlighted short-term risks for Korea, affected by external risks.

“Among South Korea’s 20 major export products, computers, mobile phones (and parts) and petrochemicals all recorded a double-digit year-on-year decline in August,” the report said.

“This was the latest signal of waning global consumer demand, particularly for electronic devices, which will have knock-on effects on domestic industrial activity.

“South Korea’s export-oriented economy is unlikely to find relief from external sources, as its main overseas markets face a period of slower growth.”

Critics also point to Korea’s heavy reliance on its largest trade partner, China, and the need to diversify its channels.

“We’ve arrived at a point where the shape of the Korea-China economic partnership that has lasted for the past 30 years has begun to change,” said Yang Pyung-seop, head of the China regional research team at the state-affiliated Korea Institute for International Economic Policy recently.

“Our partnership needs to progress from the type where we only ride on China’s back. Diversification of trade channels is needed.”