April 12, 2023

MANILA – Given the inaccessibility of mental health services, the tragic state of the National Center for Mental Health (NCMH), which Sen. Raffy Tulfo likened to a “pig pen,” seemed like a deadend for Filipinos with mental health illnesses.

Dr. Dinah Nadera, a psychiatrist, said with Tulfo’s revelation of the “heartbreaking” condition of patients at the NCMH, families of patients “will be discouraged from seeking help” from the government’s leading mental health institution.

But families being discouraged is only the tip of a more complex issue, especially since when it comes to a patients’ access to health care, “we can say that services are not available, accessible and affordable in several areas.”

“Where will the persons with mental health condition[s] go if services are not available in general hospitals?” said Nadera, a highly regarded psychiatrist actively involved in training primary health care workers in assessing and managing people with mental health illnesses.

She said this was the reason that the World Health Organization (WHO) encouraged governments to decongest mental hospitals and make mental health services accessible in communities.

This, as she stressed that in many countries all over the world, stand-alone psychiatric facilities are said to have poor conditions and that the NCMH in Mandaluyong City, which was established in 1925, is not an exemption.

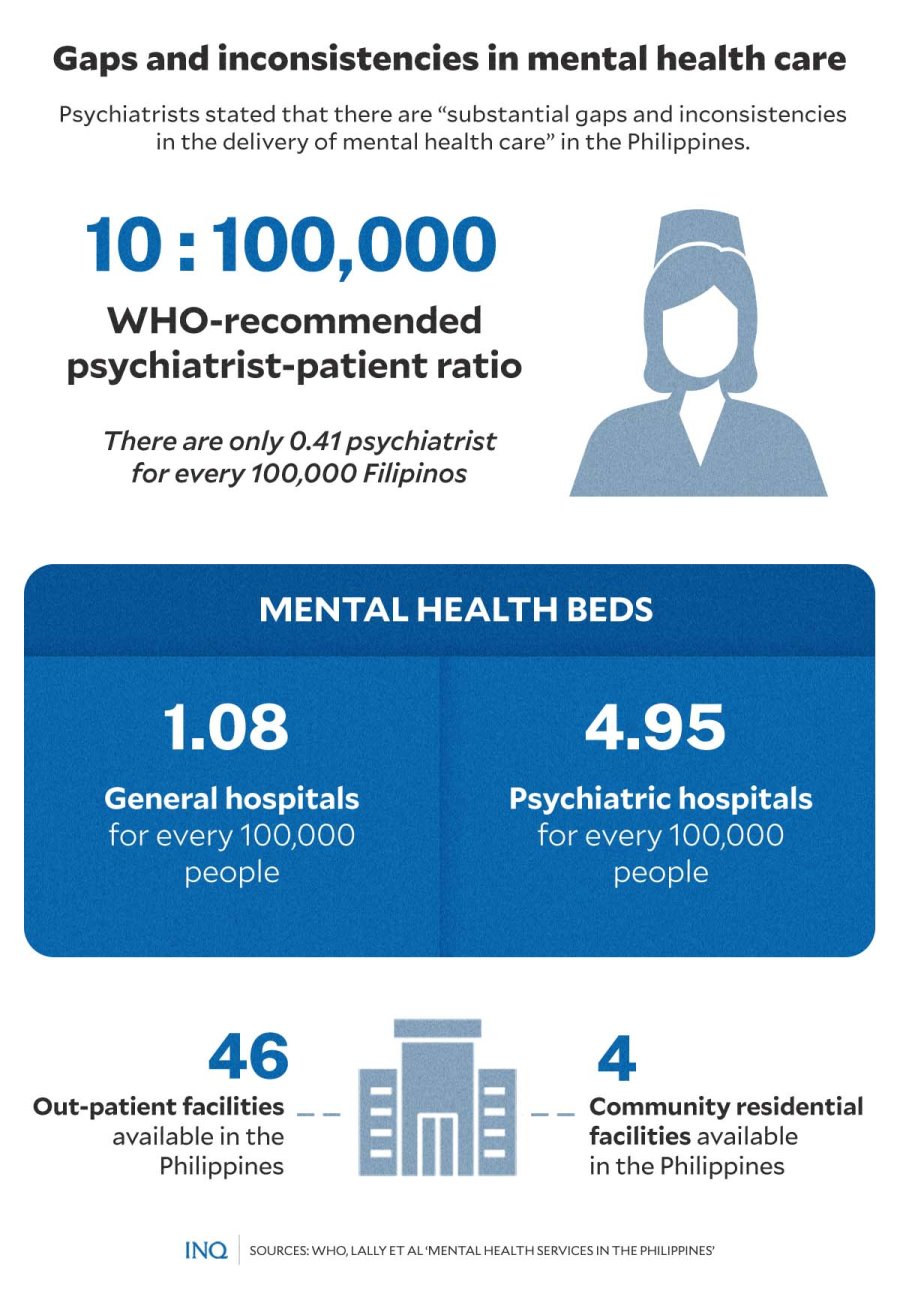

As psychiatrists John Lally, John Tully and Rene Samaniego stated in an article published by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, there are “substantial gaps and inconsistencies in the delivery of mental health care” in the Philippines.

Struggling with poverty, mental illness

It was Good Friday (April 7)—a house in Ramon, Isabela was as silent as the rest of the barangay or village, but if not because of the provision of medicines from the local government, this would not have been the case.

Staying inside an old and crumbling house are siblings Remedios, Salome, and Martin (not their real names), who are all with mental health conditions. Their mother, Virginia (not her real name), is the only one taking care of them.

STRICKEN WITH SICKNESS, POVERTY. Now calmer, Remedios and Salome (not their real names) try to live a normal life inside their old and crumbling house. PHOTO BY KURT DELA PENA

Virginia told INQUIRER.net that it was in the 2000s when Remedios and Salome fell sick, then years later, Martin became sick, too. The condition of the siblings made life tougher, she said, especially since all of them were already in poverty even before the siblings became ill.

There were a few instances that the three had been checked by a psychiatrist, and as Virginia shared, they were told that the siblings will get better if all of them would consistently take their medicines.

“This happened,” she said, but not to all of them. “Only Salome is taking her medicines regularly, so her condition improved from always being naked and often having outbursts to being silent and calm.”

NOW CALM. Salome (not her real name), diagnosed with schizophrenia, is now calm after taking medication regularly, an improvement from her previous condition of always being naked and often episodes of outbursts. PHOTO BY KURT DELA PENA

Lally et. al. stated that the 2005 WHO Health Survey indicated that “only a third of people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were receiving treatment or screening (although antipsychotic medication was not specified as the treatment).”

Virginia said if access to mental health care did not come late, the condition of the siblings would not have been “worse” and that all of them, especially Remedios, would still have been able to work and provide for the family.

She said confining the siblings to a mental hospital also came to her mind, but she feared that their condition would only get worse inside: “I was afraid that they might get harmed by the other patients and that care might not be enough.”

NCMH’s sad state

Take what Tulfo said of Pavilion 4, the NCMH’s Forensic Ward, which houses patients with pending cases. He said that the cramped pavilion with poor ventilation has roughly 50 patients even if its capacity is only up to 10 people.

He also recalled his visit to Pavilion 8, or the mental health institution’s Female Ward. He said the ward “smelled of patients’ feces and urine, which was made even awful by the smell of garbage dumped outside.”

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

“It is heartbreaking to see the tragic condition of the patients at the NCMH […] If you are squeamish, I’m certain that you’ll throw up because of the wards’ foul smell, which is worse than the smell of a pig pen.”

He said: “They are sleeping on the floor without any mat, blanket or pillow. They are cramped like sardines in a can, and the heat is like you are in an incinerator because there is poor ventilation and lack of electric fans.”

Tulfo said patients are “not receiving the specialized care and treatment they deserve because of the hospital’s poor facilities.” Tulfo made an inspection at the NCMH last March 27 after receiving a tip.

He stressed “the need to hold accountable those responsible for corruption or any lapses, negligence, or violations of laws, rules, and regulations governing mental health care services” in the Philippines.

Health Undersecretary Maria Rosario Vergeire, Department of Health (DOH) officer-in-charge, said “we are open to the investigation, and we are trying to improve the situation, and, of course, the convenience of our patients.”

Access to mental health care ‘lacking’

Nadera said there is “teeming evidence that persons with mental health conditions can be treated as out-patients in communities,” stressing the need to address the lack of knowledge and skills of health care providers in general hospitals.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

“There are reports of human rights violations partly because families and communities do not know how to deal with challenges faced when caring/encountering a person with mental illness,” she said.

As Lally et. al. stated, “there are only two tertiary care psychiatric hospitals” in the Philippines: the NCMH in Mandaluyong City, which has a bed capacity of 4,200, and the Mariveles Mental Hospital in Bataan, which has a bed capacity of 500.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

There are 12 smaller satellite hospitals affiliated with the NCMH and are located throughout the country, but “overcrowding, poorly functioning units, chronic staff shortages and funding constraints” are problems being faced, especially in peripheral facilities.

WHO data, which was cited by Lally et. al. in the article, indicated that there are only 1.08 mental health beds in general hospitals and 4.95 beds in psychiatric hospitals for every 100,000 people in the Philippines.

Likewise, there are only 46 out-patient facilities, or 0.05 for every 100,000 population, and 4 community residential facilities, or 0.02 for every 100,000 population: “Mental health [care] remains poorly resourced.”

Based on WHO’s 2007 Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems, there are only 0.41 psychiatrist for every 100,000 Filipinos, a ratio that is way lower than the rest of Western Pacific countries with the same economic statuses.

Lally et. al. said together, “these figures equate to a severe shortage of mental health specialists in the Philippines. This is further illuminated when compared with the WHO-recommended global target of 10 psychiatrists for every 100,000 population.”

“Prohibitive economic conditions and the inaccessibility of mental health services limit access to mental health care in the Philippines. Further, perceived or internalized stigma has been shown to be a barrier to help-seeking behavior in Filipinos.”

Strengthen the law

Only 5 percent of the government health care expenditure is directed toward mental health even after the Mental Health Act and Universal Health Care Act were enacted, Nichole Maravilla and Myles Tan stated in an article published by the Frontiers in Psychology.

As Nadera stressed, the Mental Health Act, which was signed in 2018 in keeping with the United Nations’ Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and for the Improvement of Mental Health Care, is “well-written.”

However, she said the law needs to be implemented properly: “Definitely, the government should address the issue that the NCMH is facing and help NCMH achieve what it should achieve according to the Mental Health Act.”

“That it should evolve into a facility that is focused on research, development of models of care particularly in the area of public mental health. It is also envisioned that the Center evolves into a center for neurology and psychiatry.”

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

The law mandated the DOH to make sure that responsive primary mental health services are developed and integrated as part of basic health services.

It provided for access to mental health service at all levels of the national health care system, affordable essential health and social services for the purpose of achieving the highest attainable standard of mental health, evidence-based treatment of the same standard and quality, regardless of age, sex, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity or sexual orientation.

Back in 2018, Malacañang said the law “forms part of the government’s mandate to design and implement a national mental health program and integrate this as part of the health information system, among others.”