January 20, 2023

SEOUL – Three years ago on Friday, South Korea detected its first case of COVID-19 or novel coronavirus disease as it was known then.

Since then, the total count of cumulative cases here reached 29,927,958, as of midnight Wednesday. This means that about 58 percent of the population in South Korea have tested positive for the virus, public health authorities say.

The country is now readying to move on from the pandemic. As the threat of a winter surge abates, public health authorities are now debating whether to lift the last of the COVID-19 measures — the indoor mask mandate and the seven-day mandatory isolation period for confirmed patients.

COVID-19 in South Korea (Graphic by The Korea Herald)

The South Korean government is confident that after the omicron BA.1 and BA.2 wave that hit around March 2022, the country can endure the rest of the pandemic without policy interventions.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare says the BA.5 wave that hit in August was an example of how the country could handle a future wave without special policies to mitigate the spread.

“Over the BA.5 wave the highest one-day death count was 122, recorded Sept. 1, which is less than a quarter of the highest one-day death count of 469 recorded March 24 over the BA.1-BA.2 wave,” the ministry said in its September report assessing the two successive omicron waves.

The caseloads did not lead to a hospital bed shortage either, the ministry said.

“After the initial omicron wave, the number of COVID-19 beds has been cut by 85 percent. Hospitals are running smoothly with the bed occupancy rate standing at around 40 percent.”

Under the omicron response plan that kicked off in late January last year, Korea ended most protective policies, ranging from free universal testing and treatment to contact tracing over the course of four months.

Those first few months were South Korea’s deadliest phase in the pandemic.

More than half of the country’s total 33,104 deaths took place during the BA.1 and BA.2 wave that lasted for about two months from February to mid-April. Days of over 300 deaths continued for weeks. This excluded people who died after the end of their hospital stay or isolation.

7-day rolling average of new confirmed cases per million people (Graphic by The Korea Herald)

The explosive omicron surge by comparison dwarfed any waves that came before. South Korea took more than two years to reach 1 million cumulative cases on Feb. 6, 2022. It took less than two months for the country to reach 10 million cumulative cases on March 23, 2022.

The process of undoing policies and practices protecting against COVID-19 began long before omicron came around. “Return to normal” was announced as a policy agenda at multiple points over the pandemic, but it was in summer after the vaccine campaign launched in February 2021 that policies started to be undone one by one.

As the vaccines, which were rolling out in an age-descending order, were just getting to people in their 50s in June 2021, then-President Moon Jae-in teased a mask-free Chuseok holiday in fall. At the time it was believed that with a high enough vaccination rate, the country could reach herd immunity.

Even after the promise of herd immunity began to fade, South Korea pushed ahead with its “living with COVID-19” plan after 70 percent of the population became fully vaccinated on Oct. 23, 2021.

One significant change was that the default approach for patients was to let them recover at home. Until then, all patients were taken to hospitals or special isolation facilities.

The change resulted in patients dying before they could be admitted to hospitals. More than 1,500 patients, most of them clinically vulnerable, were waiting for a bed to become available at one point in December 2021.

While access to hospital care, free testing and treatment were scrapped relatively early, some of the more controversial and intrusive policies were kept until much later.

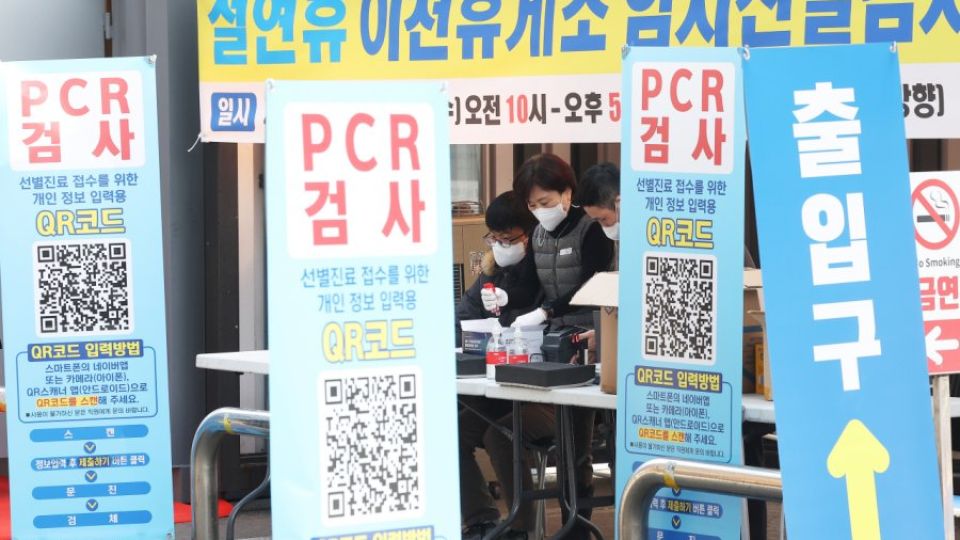

South Koreans were required to scan smartphone QR codes that give away personal information including their vaccination status to enter everyday places like restaurants until March 2022, only after courts found the mandate unconstitutional.

Nursing homes weren’t allowed face-to-face visits until October 2022. Nursing homes and elderly care institutions underwent brutal lockdowns in the first pandemic winter from December 2021 to January 2022, barring residents and workers from leaving as cases spread among them.

After a year of omicron, the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency says as many as 7 in 10 people here may have had COVID-19. In the KDCA’s Dec. 7-22 survey of antibody prevalence in 7,528 people, some 70 percent were positive for natural antibodies.

BA.5 and other omicron subvariant-led cases bounced back in November and December 2022 before slowing down at the turn of new year.

“Our case rates and hospitalization rates have fallen by 27.5 percent 12.2 percent, respectively, compared to the week before,” senior KDCA official Lim Sook-young told a briefing Wednesday.

But the slowdown in spread is accompanied by a dawdling uptake in new vaccines tweaked to protect against omicron subvariants and Seollal holiday long weekend falling Jan. 21-24.

“The winter COVID-19 wave appears to be past peak and stabilizing, but the majority of vulnerable people in their 60s and older still remain unvaccinated with the bivalent vaccines,” Dr. Jung Ki-suck, who is advising the government pandemic response team, told Monday’s briefing.

South Koreans’ enthusiasm for vaccines appears to be fading, after a successful initial vaccination campaign. While 88.7 percent of eligible people completed their primary vaccine series, only 33.9 percent of people in their 60s and above have received the bivalent vaccine, which started rolling out in October.

Oral antivirals, a shortage of which had prevented their wide distribution throughout the year, are still primarily offered to older people. In the final week of December 2022, 36.4 percent of patients aged over-60 were prescribed oral antivirals, according to the KDCA.

Another uncertainty that clouds South Korea’s road ahead is the rise of yet another variant.

Last week’s analysis showed the proportion of BA.5 was down to 28.3 percent from 34.4 percent the week prior, while the BN.1 proportion increased to 39.2 percent from prior week’s 32.4 percent. Since the discovery of a first case last month, 31 cases of XBB.1.5, which is quickly gaining ground in the US, have been identified here.

“When a new variant comes around, we are forced to be cautious until we understand it better,” said Jung. “That possibility still remains a threat, and we ought to keep it in mind.”

According to KDCA calculations, 0.11 percent of people with the virus have died. But a more complete picture of the pandemic’s impact can be found in statistics on excess deaths — the number of additional deaths compared to other years.

According to monthly updates by Statistics Korea, 304,931 people died in the country between Jan. 2-Oct. 29, 2022. That figure is about 47,000 higher than the highest number of deaths seen during the same period in the three preceding years.