December 23, 2022

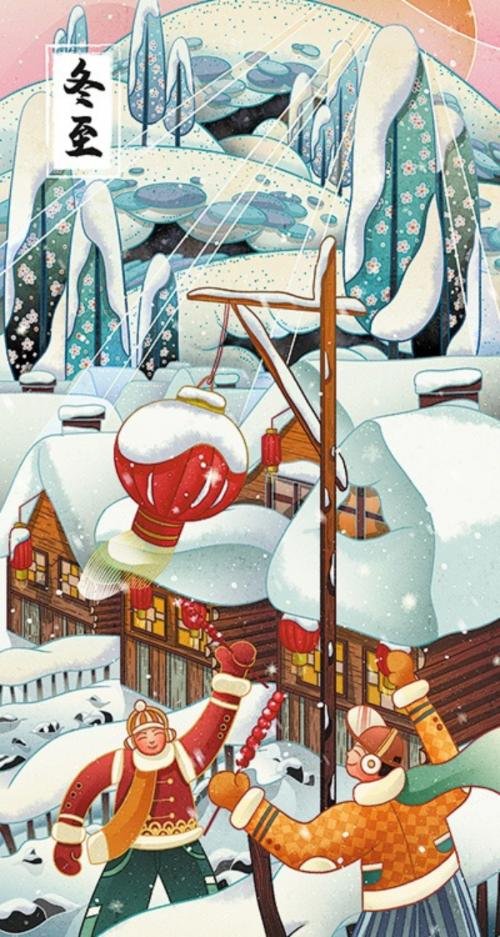

BEIJING – On Dec 21, 2016, the gate of Yang’s Family Temple in Yangjia village, Sanmen county, Taizhou city, Zhejiang province, was decorated with flags and lanterns, and couplets were pasted up. Red candles lit up the smiling faces of the villagers. For the locals, the celebration of dongzhi, or Winter Solstice, the 22nd solar term on Chinese traditional calendar, is no less important than Spring Festival.

Winter Solstice, which falls on Thursday this year, thus marks the sun’s northward return, and the days in the Northern Hemisphere will become longer

The occasion came after the practice of Twenty-Four Solar Terms was officially included on the UNESCO world intangible cultural heritage list on Nov 30 that year, and a variety of traditional folk activities to celebrate Winter Solstice were held across the country.

Since the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the descendants of the Yang family have used the Winter Solstice to pay tribute to their ancestors, and they gradually formed a set of ceremonies. In order to celebrate the success at UNESCO, Yang’s family temple underwent renovation before the ceremony.

At 4:40 am, the winter sacrifice ceremony began. The clansmen stood up, lit firecrackers and played music. The chief worshipper performed nine kowtows, three offerings, and read blessings. “Winter Solstice Festival is not just a formality, there is a lot of attention here. The more precise the movements, the more respectful we are,” the inheritor of the festival, 87-year-old Yang Yaxing, was quoted as saying by China News Service.

“It is a ceremony of gratitude to the ancestors. Through offering sacrifices to winter, it conveys gratitude to nature, highlights the moral concepts of advocating ancestral virtues, respecting the old and loving the elderly, and realizes family harmony and cohesion.”

Children eating glutinous rice balls in Rugao, Jiangsu province. (XU HUI / WEI YONGXIAN / MA DUO / FOR CHINA DAILY)

In Dengfeng, Henan province, on that very day in 2016, 10 astronomy enthusiasts used a method of observing the sky employed during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) to measure the sun and its shadow on a particular spot at noon to determine the exact angle and time of the Winter Solstice in the city’s Gaocheng Observatory scenic area in Gaocheng town. The observatory, a world cultural heritage site, is one of the oldest and best-preserved observatories in the world, founded by Guo Shoujing, an astronomer in the Yuan Dynasty.

The earliest record of putting Winter Solstice on top of the Twenty-Four Solar Terms comes from the book Huainanzi, or Great Words From Huainan, a collection of scholarly debates compiled by academia at the court of Liu An, king of Huainan, in the second century BC

On Winter Solstice in the Northern Hemisphere, the sun’s rays fall vertically at the Tropic of Capricorn, and reach their southernmost declination in the ecliptic. On that day, there is the least daylight and the longest night. Winter Solstice, which falls on Thursday this year, thus marks the sun’s northward return, and the days in the Northern Hemisphere will become longer. The traditional Chinese culture regards, in a broad sense, that the daytime is yang and night yin. Winter Solstice gives rise to yang, and the balance between yin and yang enters a new cycle. The solar term is not only a node, but also a starting point, representing the beginning of reincarnation.

The old saying that “Winter Solstice is as big as the New Year” is rooted in history. The earliest record of putting Winter Solstice on top of the Twenty-Four Solar Terms comes from the book Huainanzi, or Great Words From Huainan, a collection of scholarly debates compiled by academia at the court of Liu An, king of Huainan, in the second century BC.

It was also recorded in the Book of the Later Han, which covers the history of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220), that Winter Solstice was regarded as the beginning day of a calendar from the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century-771 BC) to the first year of Emperor Wu’s reign of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24). The classification corresponds to an old saying in southern China that “eating rice dumplings on Winter Solstice makes a person a year older”. The emperor felt the need to revise the calendar as it was no longer accurate. He ordered Ni Kuan and Sima Qian, the imperial historians, to jointly formulate the new Taichu calendar which made the first month of spring the beginning of a year. Since then, the New Year and the Winter Solstice have been separated, and the Winter Solstice was later called the sub-New Year.

Yan Songtao, director of Dengfeng Cultural Center, explains: “The astronomical division method that puts the Winter Solstice on top was abandoned, because it does not match the living habits of the common people. After Winter Solstice, there will be severe cold ahead. People do not feel the new atmosphere of a new beginning like a new year.”

(WANG XIAOYING / SUN YUE / CHINA DAILY)

However, from the imperial court to the common people, they all attach great importance to this day. The emperor would hold a grand ceremony to worship the celestial god, pray for the prosperity of the country and its people and for good weather in the coming year; while the common people would prepare meals and offer sacrifices to their ancestors. Zhou Mi, a poet in the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), wrote in his book Wulin Jiushi (Ancient Matters From the Wulin Garden): “The imperial court will celebrate the festival, just like the New Year. The carriages and horses are all new and beautiful. The five drums have filled the nine streets. The streets are seething with women and children, dressed in gorgeous clothes.”

Being one of the most important days of the Twenty-Four Solar Terms, Winter Solstice is also called jin jiu, or “entering the nines”. From that day, every batch of nine days are counted as a “nine”. After nine “nines”, a total of 81 days have passed, and cold days will not return.

People from all over the country have compiled various proverbs and jingles for counting nine “nines” to warn of the coming of the coldest time ahead and long for the return of spring. The most representative and lively of which being: “during the first nine, second nine, keep your hands covered; the third nine, fourth nine, walk on ice; the fifth nine, sixth nine, look at willows along the river; the seventh nine, rivers unfreeze; the eighth nine, wild geese come back; while after the ninth nine, cattle are about to walk everywhere”.

Eating glutinous rice dumplings is the norm in the south, whereas in the north it is mainly flour-made dumplings and wontons

After “entering the nines”, the ancient literati used to hold activities to dispel the cold. On a “nine” day, about nine people would drink wine (“wine” and “nine” are homophonic in Chinese). However, apart from the jolly, merry tone, Winter Solstice is also a heartening testimony of human determination.

From the imperial court down to the folk at that time, people maintained the custom of painting the “nine-nine cold-dispelling drawing”. One of the possible origins is traced back to a patriot, Wen Tianxiang, in the Southern Song Dynasty, who was captured by the authorities of the Yuan Dynasty and imprisoned on Winter Solstice. Years in prison pushed him to use the tip of a broken brick to paint plum blossoms on the wall. He painted 81, each of which is hollowed. He kept painting one every day, so that after 81 days, it would be the day when the earth would rejuvenate. He firmly believed that the cold winter would pass and spring would come. When word of his deeds spread across the nation, people expressed admiration for his moral character and followed suit by drawing the plum blossoms, thus forming an endearing custom of countdown to the return of spring.

A bowl of lotus root soup ready to serve. (XU HUI / WEI YONGXIAN / MA DUO / FOR CHINA DAILY)

There is a great difference in the food eaten on the day of Winter Solstice between the north and the south. Eating glutinous rice dumplings is the norm in the south, whereas in the north it is mainly flour-made dumplings and wontons. The rice dumplings are also called “Winter Solstice balls” in the south. Southerners use glutinous rice to wrap various vegetables and meat as fillings. It not only serves as an offering to the ancestors but also a gift for relatives and friends.

The custom dates back to the Ming Dynasty when women got up early in the morning on that day to start making glutinous rice balls, and the whole family ate them for breakfast to mark that the daytime was about to get longer. Later, the custom was added with a new symbolic meaning as the round shape of the rice balls also signifies reunion.

The Winter Solstice gastronomy in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, is perhaps among the most traditional and exquisite. Dinner for family reunions on that day is the most important festive event for local people. The dinner must include cold dishes and hot stir-fry, whole chicken, duck and fish, just like the Chinese New Year’s Eve dinner. On the eve of Winter Solstice, business at the braised food shops in the streets and alleys is extremely brisk with the dry-cut beef, lamb, salted chicken and smoked fish sold out fresh from the shelf.

Colorful dumplings made by villagers in Zhouzhi county, Xi’an, Shaanxi province.(XU HUI / WEI YONGXIAN / MA DUO / FOR CHINA DAILY)

However, eating dumplings on Winter Solstice is a ubiquitous part of day-to-day life in the north. One legend says Zhang Zhongjing, the great doctor in the Eastern Han Dynasty, saw on his way back to his hometown on Winter Solstice that the villagers on both sides of the Baihe River in Nanyang, Henan province, were dressed in rags and many had frostbitten ears. He wanted to help and asked his disciples to set up a shed there. He mixed mutton, pepper and some cold-dispelling herbs together, chopped them and wrapped them in dough that looked like an ear.

He then boiled them in a pot and named it the “ear frostbite relieving soup” and offered to the common people. After taking it, the frostbite was cured. Later, every Winter Solstice, people imitated his cooking, so the custom of “pinching frozen ears” was formed.

“It’s by these legends that people’s emotions are recorded and accumulated in such festive customs,” says folklore expert Zhou Dongxu. “Winter Solstice has been an important solar term since it was established. It has not only distinctive agricultural features, but also strong ethical implications and a human touch. The difference in festivals and customs between the north and the south makes up the diversity and profoundness of our culture.”