August 16, 2023

JAKARTA – The government is rushing to address Greater Jakarta’s perennial air pollution problem amid a public outcry over worsening air quality in the region in recent weeks.

Jakarta has consistently ranked among the 10 most polluted cities in the world since May. But last week, it topped global charts compiled by Swiss air quality technology company IQAir, sparking heated debate.

In response, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo convened a limited meeting with several ministers and regional leaders on Monday to discuss short- and long-term strategies to tackle the issue.

“On Sunday, the Air Quality Index in Jakarta reached 156, which falls in the ‘unhealthy’ category,” Jokowi said prior to the meeting.

The President has blamed the deteriorating air quality in the nation’s capital largely on the prolonged dry season, which has exacerbated the impact of vehicle and industrial emissions.

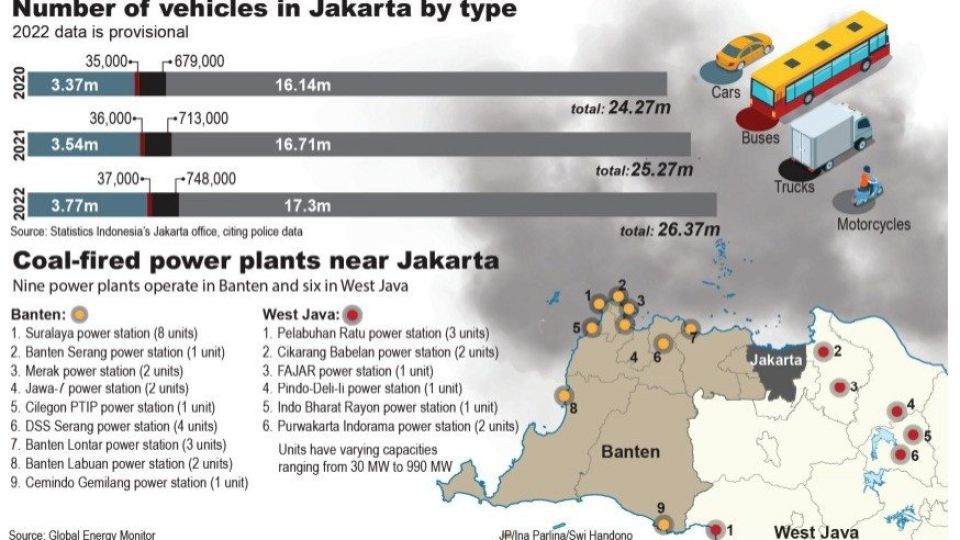

Jakarta is situated in the vicinity of 16 coal-fired power plants and remains one of the most gridlocked cities in Southeast Asia.

The Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics Agency (BMKG) has forecast that most regions of Indonesia will face a longer and more severe dry season this year compared to the previous three years as a result of the El Niño weather phenomenon, which is expected to peak in August or September.

Jokowi, himself a former Jakarta governor, said the government planned to use various strategies to address the severe pollution, including weather modification efforts, the addition of new green spaces and the implementation of remote work arrangements.

After the meeting, acting Jakarta governor Heru Budi Hartono said he would reintroduce a work-from-home (WFH) system for 40-50 percent of the city’s officials. The capital employs some 200,000 people, 60,000 of whom are civil servants.

“I have asked other ministries to implement similar measures,” he told reporters at the Presidential Palace.

Heru also said the city would more tightly monitor environmental building standards and advise owners of cars with engine capacities of 2,400 cubic centimeters or greater to use the higher-octane RON-98 fuel.

In 2012, the Jakarta administration issued a regulation to reduce the environmental impact of the construction sector. It stipulates that developers must meet strict requirements for energy- and water-efficient buildings or risk having their construction permits revoked.

Heru also promised to add more green spaces and plant more trees in the capital and noted that authorities would consider a “four-in-one” traffic rule requiring cars to have at least four passengers on major roads.

Emissions, conditions

The government has also said it will make regulating motor vehicle emissions its highest priority, as such emissions are the leading cause of air pollution in Jakarta.

Environment and Forestry Minister Siti Nurbaya Bakar said authorities were planning to enforce stricter emissions controls and planned to expand the rules to the capital’s satellite cities.

“Emissions tests are a way to force owners to inspect and take care of their vehicles. It’s a very swift measure and we can feel the impact immediately,” Siti told reporters.

Since 2020, the Jakarta administration has required owners of motor vehicles more than three years old to test their emissions annually.

Authorities in Jakarta’s satellite cities have yet to issue similar regulations, however, even though every vehicle traveling to, within or through Jakarta is subject to the city’s mandatory emissions testing rule.

Even with the policy in place, Siti revealed that only about 3 to 10 percent of the 24.5 million vehicles in the city had undergone emissions testing amid a lack of enforcement of penalties for noncompliance.

The 2020 gubernatorial regulation outlines sanctions ranging from tickets to higher parking fees for vehicles that fail to pass or undergo emissions testing. Enforcement was set to begin in 2021 but hit snags, including the COVID-19 pandemic and an insufficient number of testing locations.

Siti said the Jakarta Police would carry out random checks on vehicles and fine those that had failed or had not undergone emissions testing. She added that authorities were considering revoking licenses for repeat offenders.

The government is also planning to use emissions tests as a requirement for obtaining vehicle registration documents. Siti did not say when such a measure would be introduced or how it would be enforced.

According to a 2019 joint study by the Jakarta Environment Agency and public health organization Vital Strategies, the largest source of pollution in the capital is vehicular emissions, which account for up to 57 percent of emissions during the dry season.

A more recent study published in February estimates that air pollution causes more than 10,000 deaths and 5,000 hospitalizations for cardiorespiratory diseases in the city each year, along with more than 7,000 adverse outcomes in children. It also costs the government nearly US$3 billion annually, roughly 2.2 percent of Jakarta’s gross regional domestic product.

Acting governor Heru recently said 4 million cars and motorcycles had been added to Jakarta’s streets in the past year and a half.

With barely any room to maneuver since moving to prolong the legal process after losing a lawsuit on air pollution in 2021, the government must now seek to appease civil society organizations, environmental groups and Jakarta residents.

But officials and businesses have also used the problem to make the case for greater electric vehicle (EV) use in the capital, even though the technology’s adoption alone, without accompanying changes in the country’s power production, could have little effect on overall emissions.

Transportation Minister Budi Karya Sumadi said the government would speed up its adoption of EVs, including by ordering state-owned electricity firm PLN to build more charging stations and standardize EV battery specifications. Jakarta-owned bus operator Transjakarta is also aiming to add 42 electric buses to its fleet this year.

Previously, the government introduced Rp 1.75 trillion in subsidies for the purchase of new electric two-wheelers and the retrofitting of older vehicles.