December 15, 2022

PHNOM PENH – Apart from its main function as a water reservoir which serves agriculture, Ang Trapeang Thma or Trapeang Thma reservoir also functions as a popular tourism site. It is a wetland area, rich in fish resources and biodiversity, and is also home to many rare and endangered bird species, including cranes, greater adjutants, pelicans, purple swamp hens, milky storks and white-shouldered Ibises.

San Kimsuor, director of the Phnom Srok District Office of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment, told The Post that Ang Trapeang Thma covers an area of 2,650ha in the northeast of Banteay Meanchey province’s Poi Char commune.

Originally a part of a major irrigation system during the Angkorian period, it was expanded during the Khmer Rouge era. In 1976, about 50,000 people were forced to dig, excavate and carry soil to build dams and turn it into a major agricultural reservoir in the area.

“Ultimately, the Khmer Rouge regime’s efforts were unsuccessful, despite the huge human cost. It is estimated that as many as 30,000 people perished while working on the dam, due to exhaustion, a lack of medical treatment or starvation,” he said.

“After the Khmer Rouge occupation was overthrown on January 7, 1979 by the revolutionary forces of the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation, Phnom Srok district’s potential as an agricultural area remained unfulfilled,” he added.

The challenge was finding ways to get the water to the fields. The hated regime’s work left only a large dam, with no supporting canals or infrastructure.

In response to the challenges faced by the area’s farmers, in 2004 the government began the restoration of the irrigation systems. Thanks to a project grant from the Government of Japan, the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology were able to complete the work, which was officially inaugurated in 2006.

Heavy flooding in 2013 caused extensive damage to the infrastructure in the area, including roads and the irrigation system, but thanks to the Cambodian flood damage recovery project, the reservoir and its system were restored. The renovations were completed in 2018, at a total cost of $90.68 million. $75 million was financed by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), with the Cambodian government contributing $9 million to the project. The remainder was supported by the Australian government.

Chan Sinath, secretary of state at The Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology, told The Post that the irrigation system was modernised and now functions efficiently. The work included canals and sub-canals, along with an extensive network of water pipes. Dams and ponds were also constructed to allow people to bathe.

“Before the project was completed, the reservoir could only store 100 million cu m of water. Thanks to the modernisation work, its capacity has doubled,” he said.

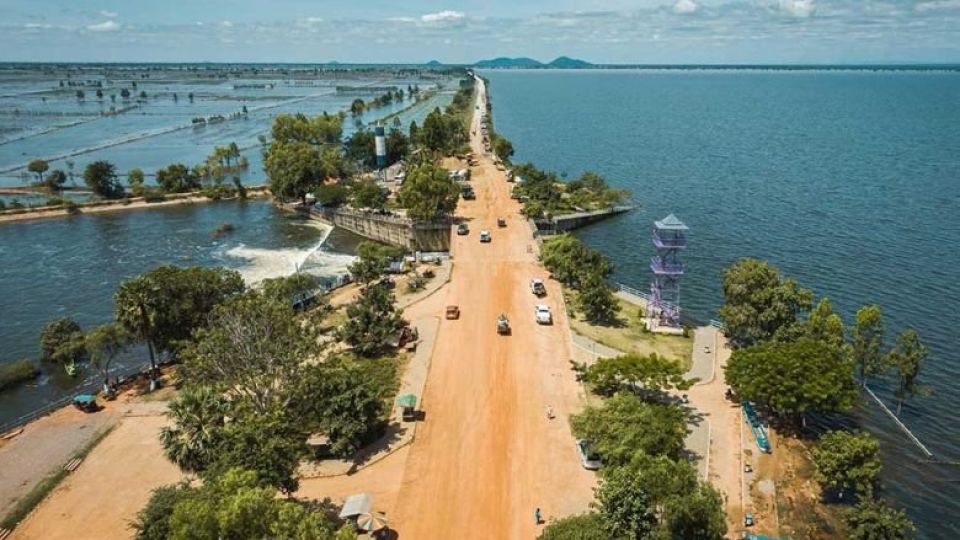

“The water is exported from the reservoir surface through a vast network of canals, sub-canals and many water lines to irrigate tens of thousands of hectares of farmers in Phnom Srok and other nearby districts. In addition, the structure of the dam was updated to include a concrete road, making it easier for farmers to transport their produce,” he added.

According to Sinath, the government has earmarked an additional $8 million for the ministry to enhance the Kingdom’s largest reservoir further. Storage is expected to increase to 300 million cu m of water when the work is complete.

“In addition to providing the water that allows farmers to harvest excellent yields, the reservoir also provides fish to the local people and is very attractive to tourists,” he said.

Due to the government’s development of the reservoir, the livelihoods of the district’s farmers have been improving year on year.

Meas Tong, a 57-year-old farmer in Phnom Srok’s Poi Char village, said that in addition to growing rice three times a year with a yield of 7 tonnes per hectare, his family and other villagers earned additional income from fishing in the canal system around the reservoir.

Another farmer, Tuy Salien, 42, told The Post that in addition to farming, she had a stall on the reverse of the dam, where she sells food to visitors.

“Each day, I can earn more than 100,000 riel by selling food to guests who come to admire the scenery,” she said.

Most of the tourists she meets come from Phnom Penh, Siem Reap, Battambang or Banteay Meanchey, she added. They enjoy bathing in the reservoir and often take boat tours to watch the abundant birdlife.

“Visitors come here every day, but there are more in the winter. They want to see the cranes, greater adjutants, lesser adjutants and purple swamp hens, and this is the season when most birds begin to migrate here,” she said.

Chhoeun Sereyvuth, director of the Banteay Meanchey Provincial Department of Tourism, told The Post that in addition to the rich biodiversity and rare and endangered wildlife, Ang Trapeang Thma is also an important historical site that attracts tourists from everywhere.

“It has been established as a historical eco-tourism site and has a steady flow of visitors every day,” he said.

Behind the dam, there are observation towers for visitors to admire the waterfowl, and an abundance of stalls selling snacks and unique souvenirs. Sight-seeing boats stand ready to escort guests on tours of the lake.

During a November visit to review the success of the project, country director of the ADB Jyotsana Varma praised the work of the stakeholders who had made the project look so environmentally friendly.

She urged all of them, especially the local residents, to help to make sure the reservoir and its network remained sustainable. She also urged farmers to diversify.

“Growing rice alone is not enough. Farmers should also be growing vegetables and raising chickens, ducks and fish. By doing so, they will ensure food security – not just in the community but across the Kingdom – and improve their families’ incomes,” she said.