April 1, 2022

DHAKA – While Covid-19 captured the attention of the world for the last two years or more, another pandemic has been silently killing countless numbers of people around the world. On March 27, this newspaper reported on an alarming finding: drugs that used to successfully fight diseases are slowly becoming ineffective because of decades of malpractice such as the intake of over-prescribed or self-prescribed medicines. This is known as antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites no longer respond to antibiotics and other antimicrobial medicines. Antibiotic resistance is a subset of AMR that applies specifically to bacteria that become resistant to antibiotics.

The discovery of this silent epidemic in the country was initially publicised in 2019, following a first-of-its-kind study by the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR). It was found that at least 10 types of bacteria had become more resistant to 17 life-saving antibiotics used for treating patients with various infectious diseases across the country. According to Dr Zakir Hossain Habib, principal scientific officer at the IEDCR, even though it was a “surveillance study; not a complete picture”, it gave “us an indication of the gravity of the situation… The threat of antibiotic resistance is growing in the country.”

Data from the following years (2020 and 2021), as well as from before (2017, 2018 and 2019), seems to confirm his fears—a report by The Daily Star on November 24, 2021, shows how the resistance trend of five of the most critical medicines listed by the World Health Organisation (WHO) has increased year-on-year.

Despite these findings, Bangladesh is already late to this game. In 2013, BestPublicHealthSchools.org had listed AMR as one of the 10 most potentially devastating public health threats on the horizon. And in January this year, The Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance report, published in The Lancet, found that more than 1.2 million people died from drug-resistant infections in 2019, while a further 4.95 million deaths were indirectly associated with antimicrobial resistance in the analysis of 204 countries and territories.

A review of AMR commissioned by the UK government warned that, by 2050, an extra 10 million people will die each year from drug-resistant infections. Against this backdrop, Bangladesh urgently needs to get up to speed to this grave threat.

We need to understand that without effective antibiotics, all manner of conditions—including pneumonia, tuberculosis, gonorrhoea, and salmonellosis—could become far deadlier. The more antibiotics are used, the more resistant bacteria become to them, meaning that humanity must guard its reserves and slow down the pathogens’ adaptive evolution by using them only when necessary. This is particularly relevant for us in Bangladesh, where, reportedly, as many as 60 percent of patients take medicines without consulting doctors or based on advices from informal providers like drug sellers and others.

But it is unfair to blame the general public alone, as there is still no effective guideline on the use of antibiotics in the country. The sale of drugs without prescription is prohibited in Bangladesh, but not punishable under the Drug Policy of 2016, which is helping the malpractice to go on. Moreover, according to a 2021 IEDCR study, doctors themselves prescribed unnecessary antibiotics to Covid-19 patients in hospitals in 83 percent of cases.

The fact that there is no scientific data on deaths or sufferings due to antimicrobial resistance at the community level in the country further exacerbates this problem. It also illustrates how this issue is yet to be taken seriously at the policy level.

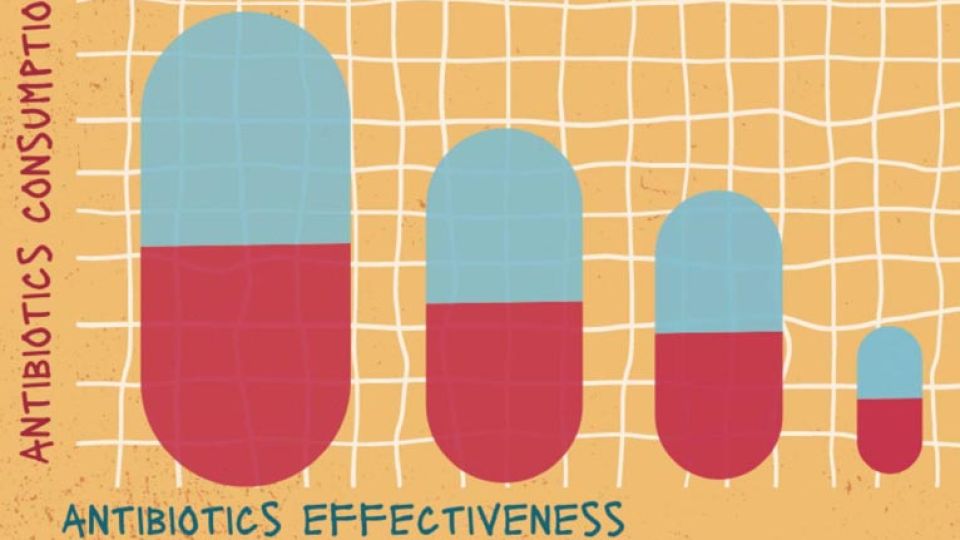

Between 2000 and 2015, antibiotic consumption decreased by four percent in rich nations, but increased by 77 percent in developing ones. The poorer enforcement of medical laws in these countries leads manufacturers to “adopt unethical marketing approaches and develop creative ways to incentivise prescribing among healthcare providers,” according to Dr Giorgia Sulis, an infectious disease physician and epidemiologist at McGill University, Canada. In her words: “A private sector that is highly fragmented and largely unregulated, where a substantial proportion of providers lack any sort of formal medical training, is extremely vulnerable to [these kinds] of bad business strategies.”

While the overconsumption of antibiotics must stop, that itself is only half the solution. Antibiotic use in food animals is another factor that contributes to AMR. This makes it a danger to global food security also.

It is time for policymakers to take this threat seriously. Spreading awareness among people and formulating the necessary policies are both urgently required.

One silver lining to this crisis is that a group of UK scientists hailed a “game-changing” antibiotic in a new study released on March 29. By developing new versions of the molecule teixobactin, they were able to successfully eradicate a superbug known as Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which had previously been resistant to antibiotics. Teixobactin had been previously acknowledged as a ground-breaking antibiotic following a study in 2015. But the new research managed to develop “synthetic” classes of the drug, allowing for easier global distribution of the treatment.

This shows the potential benefit of investing in cutting-edge research to develop new antibiotics that may temporarily solve the problem of existing superbugs. But, in the long run, we must all understand that prevention is better than the cure. This means humanity must learn to live a healthier lifestyle, rather than depending on the unnecessary use of medication.

As experts have highlighted, the key to staying healthy is maintaining good nutrition, hygiene and regular exercise, and recognising that human health is closely connected to the health of animals and the shared environment. Which means we have to stop poisoning our environment in every way and more closely monitor what gets put into the animals that we consume.