September 29, 2025

DHAKA – Amid the clamour of a bustling Dhaka railway station, a young woman stands, sketchbook in hand, each line of her pen capturing the city’s chaos and quiet alike. As trains roar past, children gather around her, curious eyes following the swift movement of her pen. For most commuters, it is an odd sight: a woman drawing in public, unbothered by the gaze of strangers. But for the cartoonist, the act is deliberate — a reclaiming of space where women are often invisible, and an invitation for others, especially girls, to imagine that they, too, belong in this frame.

In Bangladesh, where cartooning is still often seen as marginal or whimsical, an increasing number of female artists are taking up their pens to draw stories that are at once personal, political, and profoundly reflective of society. Their work does more than entertain; it amplifies voices, challenges norms, and redefines what it means to be an artist in a country still learning to embrace women in creative careers.

Why do women draw?

Every cartoonist begins with a story. For many women, it starts not with ambitions of fame but with a personal urge to express. Dhrubani Mahbub, an artist, cartoonist, and trainer, shares that her first encounter with cartooning was born from anger.

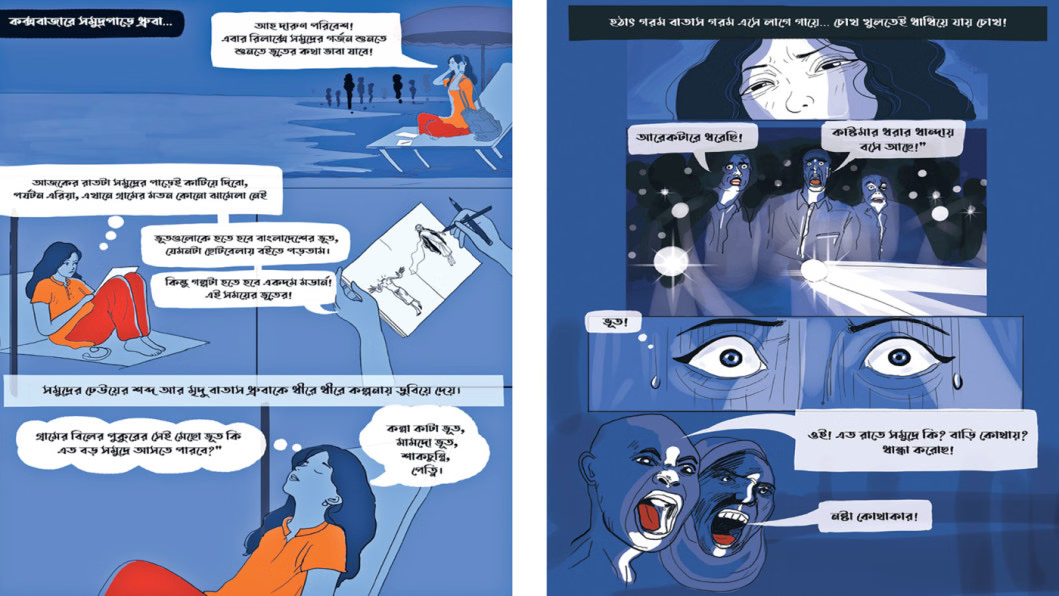

She describes the feelings behind her initial drawings as urgent, instinctive, a form of protest against social injustices. “I had a long break of five years when I didn’t draw anything at all. Then last year, after several women were harassed at Cox’s Bazar, I drew my first cartoon as a response,” she said. Drawing or making comics became an outlet for her to give form to feelings that words could not fully capture.

Pages from Bhooter Khoje, a comic by Dhrubani Mahbub, created as a protest against recurring incidents of harassment of women in Cox’s Bazar last year. PHOTO: THE DAILY STAR

For some, who grew up leafing through pages of Unmad or Rosh-Alo, secretly tracing the bold lines of the artists they admired, cartooning was a childhood dream. Natasha Jahan, a full-time newspaper artist and a bachelor’s student at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Dhaka University recalls, “I entered the community at quite a young age, back when I was still in school. From childhood, I loved reading Unmad, Rosh-Alo, and Mogoj-Dholai, which inspired me to draw. As I grew older and gained access to social media, I began sharing my cartoons publicly.” Comics and cartoons were the early sparks that shaped her love for visual storytelling.

That same spark is echoed in the journey of Sarah Saiyara, a character concept artist, illustrator, and UI-UX designer. “I’ve been cartooning from a young age, and I like this creative path because it doesn’t come with the rigid rules and regulations of photorealism.”

Another cartoonist and comic book artist, Rehnuma Proshoon, on the other hand, shares that it was not quite a childhood dream written in the margins of schoolbooks. It was a discovery sparked by curiosity and community. “I was always fascinated by Bangladeshi cartoonists and used to follow all of them on social media. One day, I came across a post about a live sketchbooking event organised by Cartoon People and decided to join. That experience completely changed things for me, and looking back, I think that was the day my journey as a cartoonist truly began,” she recalled.

Despite the differences in their beginnings, a common thread unites them – a desire to translate lived experiences, social observations, and imaginative worlds into visual narratives. For them, cartooning or making comics is a way to respond to society, to connect with people, and to communicate perspectives that are often left unspoken.

Cartooning through a woman’s lens

Does gender shape the way cartoons are drawn? Many seasoned artists think so.

“When girls draw comics, the topics become far more diverse – touching on nature, beauty standards, complexion-related racism, family issues, mental health, and self-realisation,” observed Syed Rashad Imam Tanmoy, renowned cartoonist and founder of Cartoon People. “By contrast, we male cartoonists often focus on thrillers, action, or superheroes. Female cartoonists bring many fresh perspectives to the community. As a male cartoonist, it stands out to me that not only are their observations unique, but so is their way of telling a story.”

The subject matter of female cartoonists in Bangladesh spans an impressive range, reflecting the diversity of their experiences and perspectives. Their art is playful yet pointed, weaving together childhood nostalgia, social critique, political satire, and intimate confessions. Theirs is a narrative that has been waiting to be inked – one that redefines both the purpose and the possibilities of cartooning in the country.

Alongside superhero-themed comics, men’s cartoons in Bangladesh have traditionally leaned towards heavy caricature, political satire, or action-driven stories. Women cartoonists, while not shying away from satire or political themes, often weave in subtlety and emotional nuance.

Take, for instance, a cartoon on street harassment. Rather than portraying the harasser as a grotesque caricature, a female cartoonist might show the young girl’s perspective — shrinking into herself, surrounded by oversized male shadows. The message hits harder – not through exaggeration, but through empathy.

Illustration by Sarah Saiyara from Luli, a children’s storybook about a timid girl learning to stand up to bullying. PHOTO: THE DAILY STAR

Reflecting on this subtlety, Mehedi Haque, prominent cartoonist and founder of Dhaka Comics, noted, “Girls’ comics are often slice-of-life stories, such as a mother’s hobby or a pet cat, whereas male comics tend to start with action or thrills. As an editor, I see male cartoonists often focus on grand gestures to impress, but female cartoonists tell clear, readable stories rooted in everyday life. Their works often capture home environments, family issues, and small moments, without losing sight of storytelling.”

A woman’s lens also brings visibility to what is often ignored. Their cartoons highlight intersections of class, gender, and power, widening the scope of what editorial cartooning can be. Rehnuma emphasises how being a woman gives her a perspective that shapes her storytelling, “Our experiences and challenges allow us to portray certain stories authentically, highlighting voices and perspectives that might otherwise be overlooked.” She enjoys exploring social issues alongside children’s stories. “For me, cartooning is a way to both raise awareness and create joy,” she mentioned.

Dhrubani’s work, meanwhile, directly confronts gender disparity, social injustice, and crises of dignity. Regarding one of her recent works, Attoupolobdhi, she said, “It is based on one of my wishful thoughts. I want to see every person in this society with equal dignity, whether they are women, men, or any other gender.”

Through her campaign Haway Aki (Moon Method), she engages children across the country, drawing on streets, in fish markets, and near railways, encouraging them to imagine and create without the constraints of pen and paper.

Whether through satire, protest, or playful whimsy, women are using cartoons to illuminate experiences, translating observation into art and art into conversation, making their work as much about empathy as it is about entertainment.

Struggles behind the sketches

Despite their passion and talent, female cartoonists in Bangladesh face both visible and invisible obstacles. Rehnuma notes that creative careers are not always fully recognised or supported. The first hurdle often comes from family and societal expectations, a barrier many young women must navigate before pursuing professional opportunities.

Natasha details another layer of challenge: the social dynamics within professional circles. Informal networking often takes place in male-centric spaces, where critical discussions happen in roadside tea stalls. For young female artists, entering these spaces and gaining credibility can be daunting. “At the early stage, I used to feel irrelevant — small, young, and different,” she said. Yet navigating these dynamics becomes a form of resilience, shaping both their confidence and their work.

Outside urban centres, these challenges intensify. Opportunities are scarcer, platforms are fewer, and awareness of creative communities is limited. For many aspiring cartoonists, the hurdle is not talent but visibility — how to bridge the gap between their work and the audiences, anthologies, or exhibitions that can elevate their careers.

How to empower the next generation

Support for female cartoonists can come in many forms: mentorship, community, exposure, and validation. Rehnuma stresses the need for professional opportunities, paid projects, workshops, and platforms where women can showcase their work. Dhrubani’s engagement with children illustrates the power of visibility, of simply being present to inspire others to pick up a pen or tablet.

Natasha underscores the importance of structured initiatives — anthologies, publications, and competitions. She points to recent publications, like Porichoy, Lines and Dreams by Cartoon People and Oboni by Dhaka Comics, which collectively featured works from around a hundred female cartoonists. These initiatives do more than celebrate talent; they provide pathways for young women to debut themselves, to claim a place in a profession historically dominated by men.

“Even if many female cartoonists have amazing works, not many people know them because they don’t showcase it anywhere. The community doesn’t know them, they don’t know us, but they exist,” Natasha explained.

For young artists aspiring to enter into the realm of cartooning, their advice is consistent: start, continue, and persist. Rehnuma encourages young women to begin and keep going, emphasising that the key is to enter the creative arena and remain visible.

“Cartooning is a growing industry in Bangladesh, and there’s room for new voices. If you enjoy it and want to pursue it, just start. Share your work and put it out there,” she said. “There are supportive communities to join, and you can even reach out to individual artists, as most are passionate and happy to guide you.”

Dhrubani highlights the importance of practice over perfection, “Continuing to draw is more important than whether I draw amazingly. To let people know that I exist as an artist/cartoonist — that I belong in the community — is the real step.” Natasha urges aspiring cartoonists to read widely and immerse themselves in a diverse array of comics from different countries, not only to learn technique but to rediscover inspiration and feed creative imagination.

Redrawing the narrative

As platforms expand and visibility grows, the contours of Bangladesh’s creative landscape are changing, and the ink of these women’s narratives is proving indelible. The sketches, comics, and illustrations made by the female artists are not only art; they are calls to imagine, to reflect, and to act. Women are now stepping into spaces once considered male domains, redefining what stories can be told, and how they can be told. They challenge assumptions about who gets to speak, what perspectives are valid, and which experiences deserve artistic exploration.

Through their pens, pencils, and digital tabs, female cartoonists illuminate the subtle and overt inequities of society. In their hands, cartooning becomes a powerful form of cultural commentary, social advocacy, and personal expression. Their journey reflects the intersection of art, gender, and society: a reminder that creativity, when coupled with courage, can redraw boundaries, dismantle stereotypes, and forge new cultural pathways.