October 23, 2025

SINGAPORE – Mr Lim Yi Ping walked away from a job as a healthcare marketing strategist in 2024 and into the unknown, betting that artificial intelligence (AI) would pay off.

The 34-year-old, who is single, took various courses on AI, spending up to eight hours a day experimenting with various tools. The Singaporean taught himself to stage live demos on automating workflows and generating content in a corporate voice.

The gamble worked. When it came to job hunting earlier this year, three out of four interviews for roles in marketing ended in an offer.

“If you don’t use AI, you might lose out in job seeking,” said Mr Lim, now a digital marketing strategist at FOZL Group, an accounting and advisory firm headquartered in Singapore.

But across South-east Asia, the picture is not always as bright.

In Manila, 46-year-old call centre worker Mylene Cabalona has seen colleagues abruptly reassigned, accounts shut down without warning and entire teams displaced.

“Of course I feel threatened because I know eventually our jobs could become redundant or there would be layoffs because of AI,” said Ms Cabalona, who also heads the labour group BPO (Business Process Outsourcing) Industry Employees Network. “AI can easily be improved (upon). It’s scary!”

She said call centre agents are now monitored by AI tools that track tone and sentiment in real time, penalising staff who do not sound upbeat enough, even when speaking to irate customers.

“We’re expected to use positive or cheerful words no matter what,” she said. “Even if the customer is shouting or clearly frustrated, we can’t mirror that tone or even just sound neutral. The system marks us down for that.”

Such requirements, she added, create emotional strain by forcing workers to suppress their own reactions just to satisfy what an algorithm defines as “good customer service”.

The stories like Mr Lim’s and Ms Cabalona’s – one of reinvention, the other of potential retrenchment – are becoming increasingly common as companies and industries across the region embrace the AI tidal wave.

A survey published in August by IDC and UiPath revealed that 86 per cent of South-east Asian organisations expect to adopt AI “agents”, or programmes that can handle multiple tasks, within the next 12 months, up from 42 per cent already doing so.

Meanwhile, the 2024 e-Conomy SEA report, released in November 2024 by Google, Temasek and Bain, notes that more than US$30 billion (S$39 billion) was committed in the first half of 2024 alone to build AI-ready data centres across Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia.

Consulting firm Kearney estimated in 2020 that AI might add nearly US$1 trillion to regional gross domestic product (GDP) by 2030.

The outlook of this new form of technology may be buoyant, but the swell across South-east Asia is uneven.

Singapore, with the region’s densest AI talent pool, is seen to be riding high. A BCG report in April estimated that the city-state has about 3.5 AI professionals per 1,000 workers, far ahead of Malaysia at 0.5, and the Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam, which hover around 0.2 each. Figures were not available for the other countries in the region.

This divide threatens to hollow out mid-skill service jobs and hit not only certain sectors and groups but also entire countries hardest, which risk deepening inequality within and across borders.

Reskilling and developing regionwide standards for AI use may help spread the benefits of this technology more widely, but without agile policies and stronger cooperation, observers warn that the rising tide of AI could just as easily worsen a divisive fault line.

AI’s promise and the potential to divide

Across the region and the world, nations are betting on AI to boost productivity and unlock new economic gains.

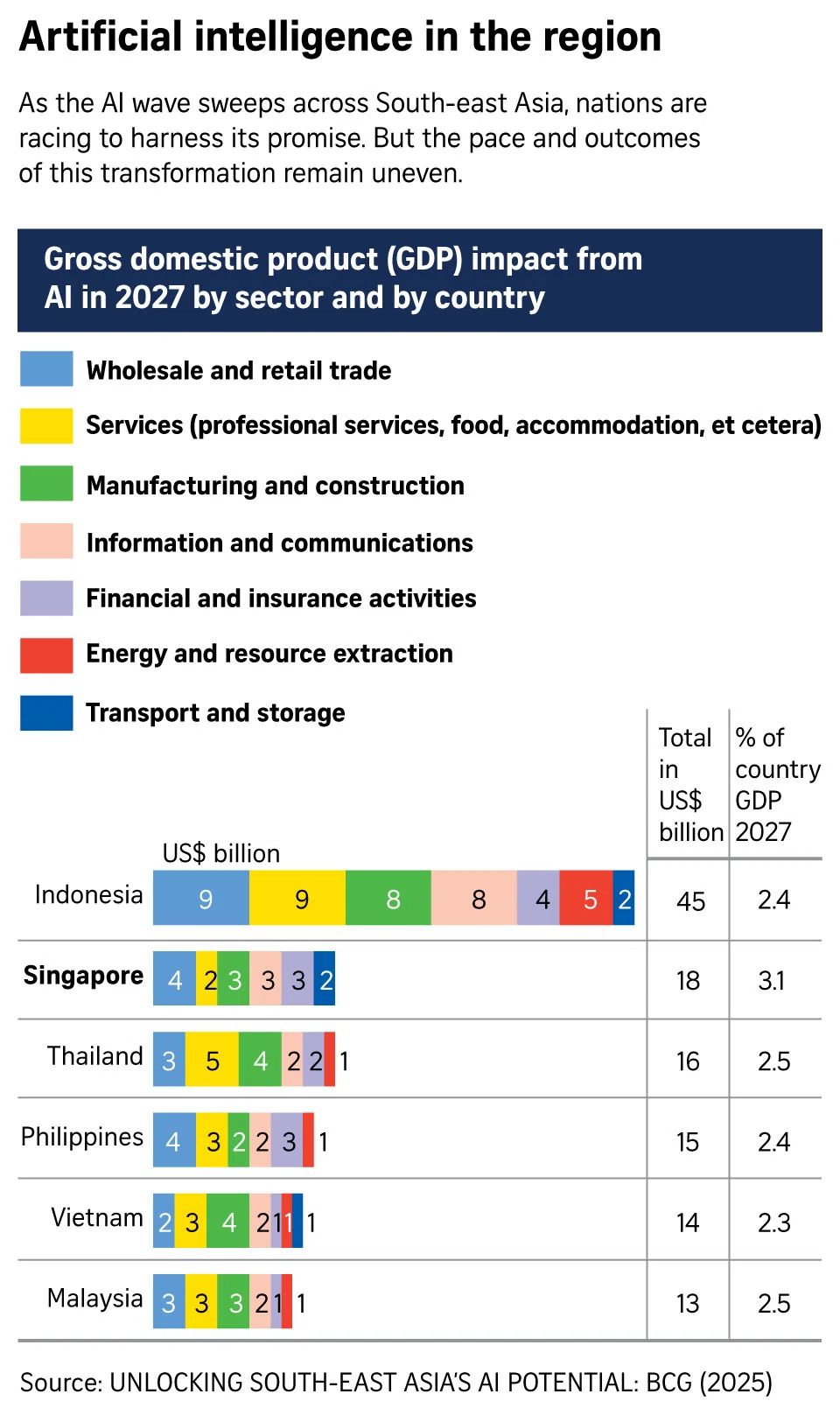

The same BCG report projected that by 2027, AI could boost the combined output of Asean’s six largest economies – Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam, collectively known as the Asean-6 – by as much as 3 per cent each. Singapore is expected to gain the most relative to its size, while Indonesia would see the biggest overall increase.

At Singapore’s National Day Rally on Aug 17, Prime Minister Lawrence Wong mentioned AI about 40 times as he outlined the Republic’s vision to drive productivity through widespread adoption of the technology.

In 2024, Singapore pledged over $1 billion to develop its AI ecosystem over the next five years, and announced another $150 million in 2025 to help firms adopt the technology.

In Malaysia, Microsoft pledged US$2.2 billion in 2024 to boost cloud and AI capabilities. And in Indonesia in November 2024, sovereign wealth fund INA teamed up with Granite Asia to channel up to US$1.2 billion into tech and AI.

However, the upbeat numbers hide an imbalance, with public data showing that the gains of AI investment might be concentrated in just a few countries.

Data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development shows that Singapore has attracted US$8.4 billion in AI venture capital, three-quarters of Asean’s total.

By comparison, Indonesia has drawn just under US$2 billion, while Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia have secured only a fraction of that.

Similarly, a 2024 Lazada–Kantar study tracking actual business use of AI in Asean shows just how uneven adoption remains. Indonesia and Vietnam lead with 42 per cent of online sellers already using AI tools, while Singapore and Thailand sit in the middle at 39 per cent. The Philippines and Malaysia trail at 32 per cent and 26 per cent respectively.

“In the near term, AI is more likely to widen gaps in South-east Asia,” said Miss Joanne Lin, a senior fellow at the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, noting the different “starting level” among nations in the region.

This, she observed, is due to varying levels of basics such as reliable power, affordable connectivity, access to cloud computing, digital skills and data governance.

“Digitally advanced economies will feel the productivity lift sooner while those less advanced members will see slower, patchier gains because adoption is harder outside major cities and without the support of large MNCs (multinational corporations) or firms.”

Dr Jayant Menon, a visiting senior fellow at the same institute, echoed her views, adding that nations late to AI will be at a disadvantage.

Given that less well-off countries have limited digital infrastructure, the gap is unlikely to narrow soon, said Dr Menon. He added that the relatively low skill levels of their workers, along with the limited quality and versatility of educational institutions, will also constrain poorer nations in preparing for the challenges of AI.

“The AI revolution is likely to increase the disparities that currently exist within and between countries in South-east Asia. This is mainly due to the fact that the more developed countries are better prepared to take advantage of the opportunities presented by AI,” said Dr Menon.

Some 164 million jobs disrupted

The uneven spread of AI’s benefits is most visible in the labour market, where the technology risks widening divides both within and between countries.

A study by Access Partnership in January estimated that 57 per cent of South-east Asia’s workforce, or 164 million people, could see their jobs reshaped or disrupted.

Professor Jochen Wirtz of NUS Business School told The Straits Times that the impact will be felt first in service-heavy industries. “Over the next three to five years, AI will automate many low-level service roles across South-east Asia, especially call centres, business process outsourcing, and shared services such as payroll and finance,” he said.

He pointed to the Philippines, where millions work in outsourcing, warning that automation could erode the advantage of labour costs and shift investment to stronger digital hubs in other countries.

In the Philippines, the US$35 billion BPO sector employs nearly two million Filipinos and makes up 8 per cent of the nation’s GDP. Retrenchments remain modest so far, with about 8 per cent of BPO firms reporting reductions in headcount in 2024, though 13 per cent said hiring had increased.

In Singapore, the disruptions of AI would be cushioned by stronger training systems and higher-skilled roles.

For a start, AI will transform jobs rather than replace them outright, said Professor Terence Ho of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. However, it is likely to reduce clerical and administrative roles over time, as well as those in customer service, copywriting and software programming, he added.

At the same time, new roles will emerge. Prof Ho pointed to DBS Bank announcing in February plans to cut 4,000 contract and temporary jobs over the next three years, while creating 1,000 new AI-related positions.

Sectors most transformed by AI, such as information and communications technology and media, stand to gain the most in productivity but also face the sharpest disruption, Prof Ho said. Entry-level positions are particularly at risk, as AI has the potential to replace many junior roles.

LinkedIn data from January showed women and younger workers dominate the jobs most likely to be vastly reshaped by generative AI, which include roles with relatively little emphasis on higher-level people-engagement skills, such as those involving repetitive and structured tasks. In Indonesia and Singapore, more than 70 per cent of women are in such jobs, compared with 62 per cent to 64 per cent of men.

In Malaysia, analyst Amir Fareed Rahim of KRA Group said evidence so far shows that women, younger workers in their 20s and 30s, and those in mid-skilled clerical or administrative roles are most exposed to the risk of job losses. “(This is) because these jobs involve structured, predictable tasks that generative AI can easily replicate,” he said.

AI’s impact on the region is also not a simple tale of the rich getting richer and the poor falling further behind. A World Bank report released in June, Future Jobs: Robots, Artificial Intelligence, And Digital Platforms In East Asia And The Pacific, noted that while AI is beginning to reshape work, its effects are mixed – displacing some roles even as it augments others.

Jobs that rely heavily on routine cognitive tasks, such as data processing or translation, face the most pressure, said the report, while those requiring creativity or human interaction may be enhanced by AI rather than replaced.

Observers agree, noting how looking at AI purely through national lenses risks missing this complexity.

Prof Ho said: “Work that involves manual dexterity – working with hands – is less prone to displacement because robots have a longer way to catch up with human dexterity than AI (does) with humans in many cognitive tasks.”

Farmers get AI boost

Still, even farmers are turning to AI, such as 54-year-old Jamras Inpuek in Thailand.

Based in Lopburi, two hours north of Bangkok, Mr Jamras grows sunflowers and sells the edible seeds directly to consumers. To cope with shifting weather patterns, he has experimented with AI-powered apps that generate a digital layout of his farm and forecast rainfall months in advance.

The predictions were only “60 per cent to 70 per cent” accurate, he said, but when they proved right, his yields rose by as much as 20 per cent, a significant margin in farming where climate often determines income.

Thailand is now trying to replicate more such success stories.

In February, its National Electronics and Computer Technology Centre launched a smart agriculture platform called HandySense B-Farm. The system combines AI with internet of things sensors to track soil moisture and seedling conditions in real time, helping farmers improve planning and boost yields.

But not every country or sector will see such gains.

Dr Maria Monica Wihardja of ISEAS warned that without stronger skills policies, middle-income countries could see their mid-skill workers squeezed out of stable employment.

“Current evidence in Indonesia and other countries like Vietnam shows that mid-skill service jobs such as sales and customer service workers are already being hollowed out,” she said.

Dr Monica added that without better skill development, the risk is that workers will move into less-skilled or labour-intensive jobs like those in agriculture or front-line services rather than move up the value chain.

Miss Elena Chow, founder of talent consultancy ConnectOne, said that AI is now woven into nearly every stage of the job hunt and understanding it will one day become as basic as knowing how to use applications like Microsoft Word or Excel.

In order for job seekers to stand out, they must not only have theoretical knowledge but have also put into practice some of it in their own life.

“Go for practical courses, not theory, like learning how to code with AI or optimising agentic use cases or open-source models – and then build something for your own use like an expense tracker, a calorie tracker,” she added.

AI and Asean cohesion

The good news is that South-east Asians are among the most enthusiastic about AI.

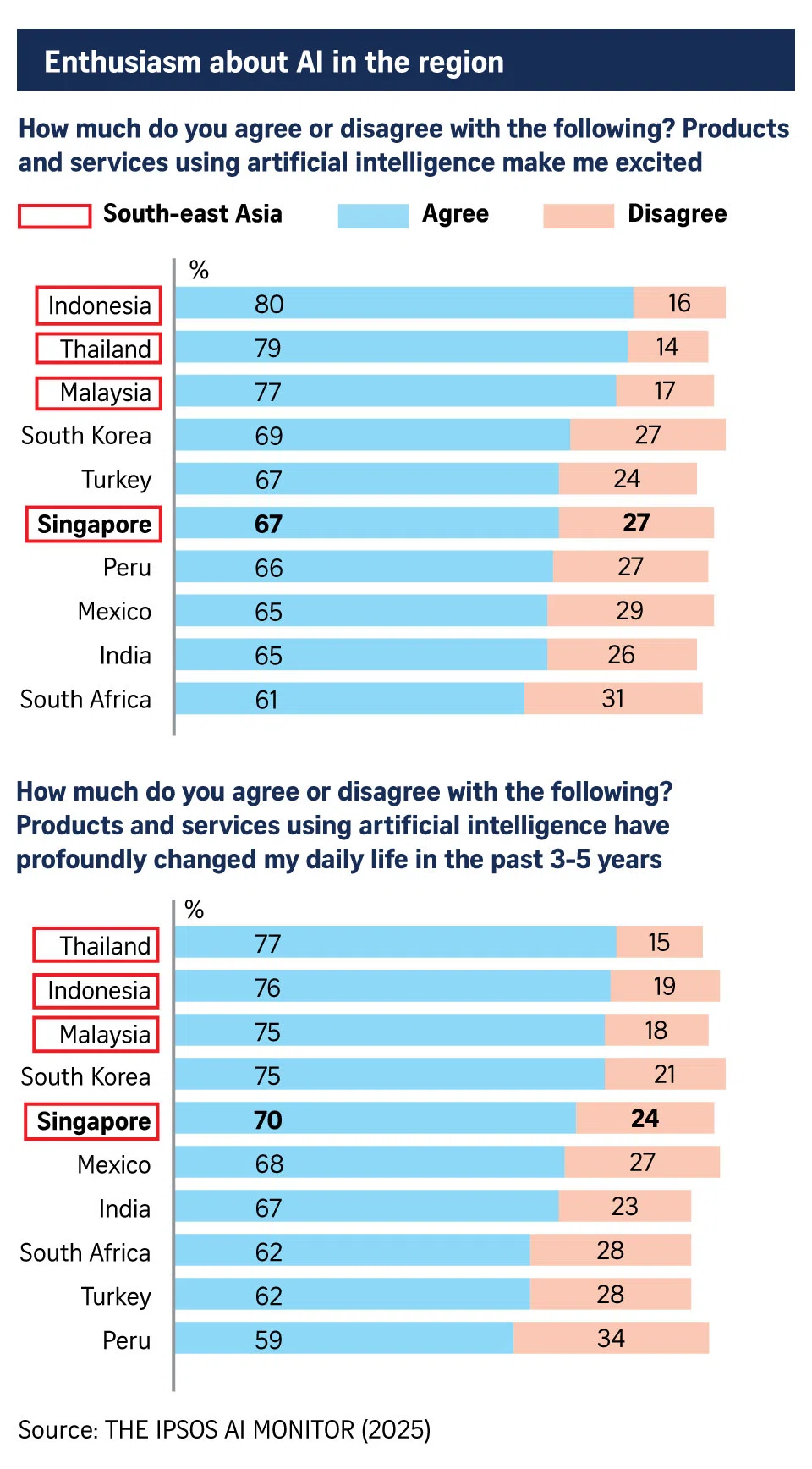

An Ipsos survey from June shows that eight in 10 respondents in Indonesia said products and services using the technology excite them, followed by 79 per cent in Thailand, 77 per cent in Malaysia and 67 per cent in Singapore. The global average was 52 per cent.

That enthusiasm is reflected in daily life. About three in four people in Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia, and seven in 10 in Singapore, say AI has already changed how they live over the past three to five years. This compares with about half of respondents worldwide.

Still, optimism is mixed with unease, the same study suggested. Nearly two-thirds of workers in Thailand, and more than half in Malaysia and Indonesia, fear AI could replace their jobs within five years, while in Singapore the figure is 50 per cent.

Across Asean, the uneven pace of AI adoption threatens to harden divides between advanced and less-prepared economies, hurting the 10-member regional grouping’s cohesion.

Observers warn this could undermine its ability to coordinate policies, share opportunities across borders and present itself as a credible destination for global investors.

“There is an existential risk in AI adoption driving a wedge between members of Asean, if not harnessed properly and governed effectively through sustained regional cooperation,” said Dr Mustafa Izzuddin, a senior international affairs analyst at Solaris Strategies Singapore.

He also pointed to the potential for AI-driven cyber attacks, deepfakes and overdependence on opaque systems to sow discord and strain trust among member states.

If AI becomes a fault line, it will slow Asean’s drive towards a single market and production base, said Miss Lin. “Supply chains (would) re-centralise in a few digital hubs while firms in lagging economies will struggle to plug in,” she added.

The grouping has been moving to strengthen its digital appeal. In 2023, it launched the Digital Economy Framework Agreement (DEFA) to boost cross-border digital trade and services, with studies suggesting it could double Asean’s projected digital economy value from US$1 trillion to US$2 trillion by 2030.

In 2025, Asean followed up with the Responsible AI Roadmap (2025-2030), setting out actionable steps for policymakers and stakeholders to promote responsible use of the technology across member states.

Data collated by AI Singapore from Hugging Face, a collaborative platform for the machine-learning community, indicates that 73 per cent of existing large language models (LLMs) come from the US and China. And 95 per cent of these models are primarily trained on data in English, or with a mix of Arabic, Chinese or Japanese.

South-east Asia’s developers have sought to level the AI playing field by building language models that better represent the multiculturally diverse region’s languages, world views, and values.

In a Project Syndicate commentary published in June, Ms Elina Noor, a senior fellow in the Asia Program at the US-based think-tank Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, noted that as platforms like Google’s models and OpenAI’s ChatGPT took off, South-east Asian developers quickly saw the need for AI that could “speak to the region in its own words”.

But creating regional AI is about more than technology, she stressed. It also means filtering out old biases, questioning assumptions about identity and drawing on indigenous knowledge stored in local languages. “We cannot project our cultures faithfully through technology if we barely understand them in the first place.”

Singapore, for one, has sought to share its head start through Sea-Lion, a $70 million LLM launched in December 2023. Open-source and tailored for South-east Asia, it recognises 13 languages, from Javanese and Sundanese to Malay, Thai and Vietnamese. With more than 235,000 downloads, it is already being adopted by firms such as Indonesia’s GoTo Group.

Other multilingual language models include SEA-LLM and Sailor, while monolingual models such as Indonesia’s IndoBERT, Malaysia’s ILMU and MaLLaM, Thailand’s OpenThaiGPT, and Vietnam’s PhoGPT have also made their appearance.

Crafting localised LLMs makes sound business sense, as nations collectively and individually embark on ambitious data-driven transformation plans.

Asean’s regional efforts can play a meaningful role in narrowing the divide by aligning rules on data flows, setting common skills standards and encouraging talent mobility. But the pace of progress will still hinge on national policies, noted Miss Lin.

“AI infrastructure like broadband access and national IT literacy programmes will be determined by individual (members) according to their national development plan. That said, Asean can close parts of the gap through initiatives like the DEFA, which is undergoing negotiations,” she said.

Observers say Asean must press on with AI integration.

Dr Mustafa suggested that the grouping may even need to add a new “community pillar” on digital governance to its existing economic, political-security and socio-cultural frameworks.

Yet, even as the region’s leaders wrestle with how to close the gaps, many workers are taking matters into their own hands.

Associate Professor Hasyiya Karimah Adli, a 38-year-old Malaysian who trained as a chemist, said AI has transformed her career path. In 2020, she pivoted into data science after realising machine learning could optimise renewable energy systems. “This sparked my passion for bridging engineering science, internet of things and AI,” she said.

This inspired her to go deeper into this field, and she is now the founding dean of the Faculty of Data Science and Computing at Universiti Malaysia Kelantan.

Mr Lim, the Singaporean, said he does not regret taking time off to deepen his understanding of AI, though he acknowledged not every industry affords such a break.

In today’s job market, it is no longer enough to show basic familiarity with AI tools, as employers want to see concrete, innovative applications.

“Right now, not many people are adept at using AI, so if you are, it’s a real advantage. In the years ahead, learning AI will become essential,” he added.