April 27, 2022

JAKARTA – ASEAN leaders should welcome United States President Joe Biden’s Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, but never as part of the overall US security strategy in the region. Instead, when ASEAN leaders meet with Biden in Washington, DC, next month, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo should push Biden to incorporate his initiative into the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. While both emphasize economic cooperation, Biden’s framework excludes China, while the ASEAN Outlook seeks to promote economic cooperation that includes everyone in the region, including China. One is clearly superior and more workable than the other.

The White House has announced that Biden will host the special summit with leaders of the ASEAN on May 12-13 to demonstrate the US’ enduring commitment to ASEAN, recognizing its central role in delivering sustainable solutions to the region’s most pressing challenges.

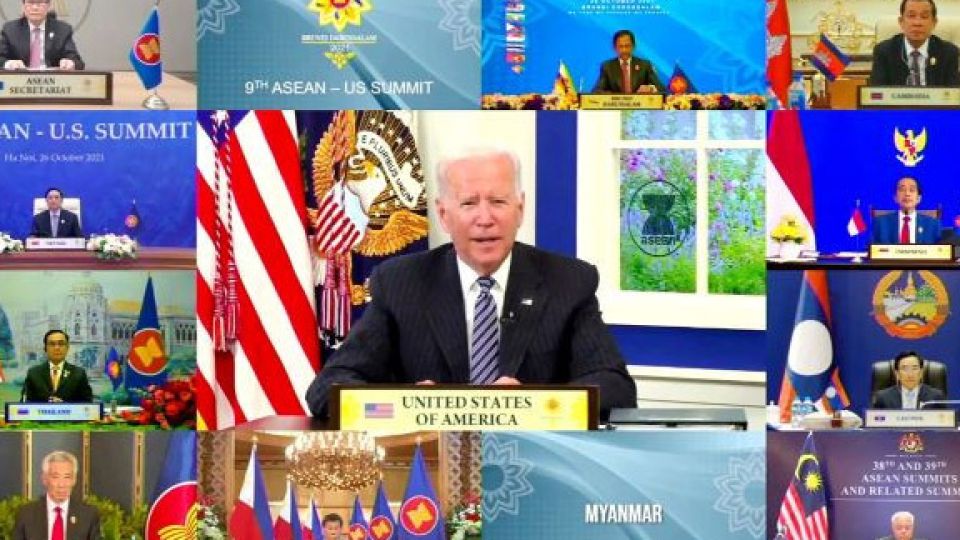

“Our shared aspirations for the region will continue to underpin our common commitment to advancing an Indo-Pacific that is free and open, secure, connected and resilient,” said White House spokesperson Jen Psaki. Biden is expected to explain in more detail the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, which he first unveiled in October 2021, and secure ASEAN leaders’ endorsement.

There is every reason for ASEAN leaders to accept Biden’s initiative for more economic collaboration for countries in the Indo-Pacific region. Thanks to Biden’s predecessor, Donald Trump, the US removed itself from the region’s most important trade arrangement when it pulled out of negotiations on the creation of the Trans Pacific Partnership in 2017. The Comprehensive and Progressive Treaty for Trans Pacific Partnership agreement was eventually signed in 2018 by 11 countries, including some ASEAN countries and without the US.

The US’ absence in the region was all the more glaring when the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RECP) — which includes all ASEAN members and China, Japan, Korea, Australia and New Zealand – came into force in January.

Biden’s Indo-Pacific economic framework would make up for the missing piece to help ensure that the 10 ASEAN members continue to have strong engagement with the US, still the world’s largest economy and a significant market for their exports. But the way the framework is presented leaves a strong impression that it is part of Washington’s overall strategy to contain the rise of China, with which it has been engaging in tough trade wars. It certainly follows early initiatives that seek to strengthen US military presence in the Indo-Pacific region to match that of China.

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, involving the US, Japan, Australia and India, has been expanded to include discussions about non-security issues such as the COVID-19, climate change, economic collaboration and counterterrorism, but it is still essentially an anti-China alliance. When Quad countries began distributing COVID-19 vaccines to other countries last year, it was designed to match China’s aggressive vaccine diplomacy. There are already talks about expanding its membership with the “Quad-Plus”.

In October 2021, the US announced the formation of the Australia, United Kingdom and US (AUKUS) security pact to further strengthen its hand in the Indo-Pacific region. The deal includes supporting Australia to develop its nuclear-powered submarines.

ASEAN has its own worries about the rise of China, which is no longer as peaceful as it was made out to be in the first decade of the millennium. China has begun to assert itself militarily in the South China Sea, where it has overlapping territorial claims with some ASEAN countries. But joining or supporting any US-led alliances, including Quad or AUKUS, would be the wrong way to go for ASEAN, for it would only invite China’s wrath. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, on the pretext of securing its border against the expansion of NATO, should serve a lesson that China might do something similar in the Indo-Pacific region to secure its interests if pushed too hard.

The situation in the Indo-Pacific region does not merit the creation of more security alliances. Instead, ASEAN should seek a stronger economic engagement with the US — and with other countries for that matter — to ease tensions and prevent war. This is where the ASEAN Indo-Pacific Outlook comes in. Signed by its leaders in their summit in Singapore in 2019, the outlook has since gained recognition from many other countries — though perhaps not necessarily their full support. Biden, in a virtual summit with ASEAN leaders in October 2021, recognized ASEAN’s centrality in the Indo-Pacific region. A month later, China’s president Xi Jinping, in his own virtual summit with ASEAN leaders, proposed linking his Belt and Road Initiative to build economic infrastructure from Asia to Europe.

The ASEAN Outlook, with the aim of promoting peace and prosperity in the region, contains principles such as openness, transparency, inclusivity, a rules-based framework, good governance, respect for sovereignty and non-intervention. And more importantly, it emphasizes ASEAN centrality in this emerging regional architecture. Since the outlook is an Indonesian initiative, it is now up to President Jokowi to convince Biden in the May summit to align the Indo-Pacific economic framework with the ASEAN Outlook. Both have the same objectives of promoting common prosperity; they are just different in their approaches.