March 2, 2023

JAKARTA – The ramifications of a recent assault involving a Jakarta university student have extended far beyond what anyone could have expected, with the case eliciting public calls to boycott this year’s income taxes because the suspect was the wealth-flexing son of a high-level tax officer.

Finance Minister Sri Mulyani has taken steps to contain the damage. On Sunday, she made the unprecedented move of instructing taxation director general Suryo Utomo to explain the details and provenance of his wealth to the public.

However, such initiatives will be useless if no systematic strategy follows. Next time a tax officer is accused of abusing power for riches and luxury, these same ad hoc measures will likely be repeated to put out the fire, but the culture of corruption will carry on.

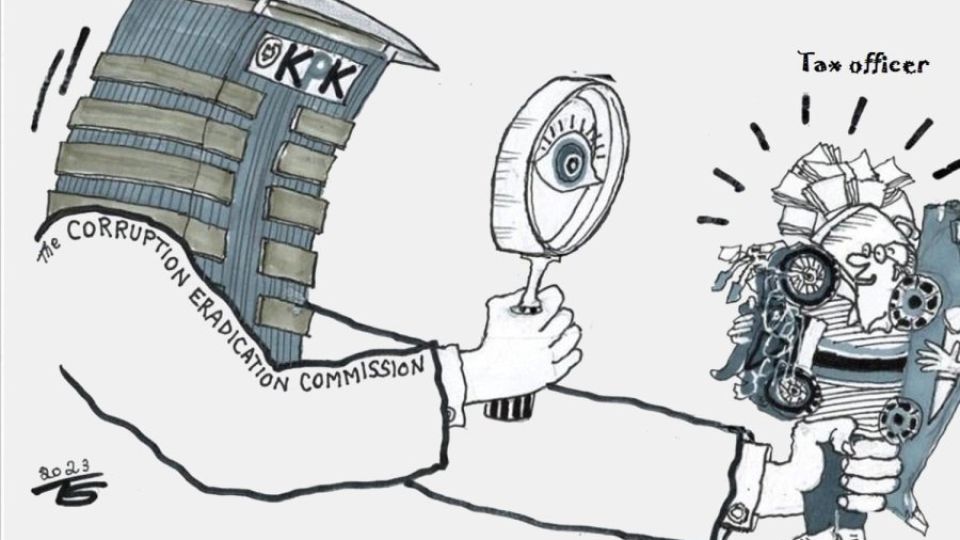

In November 2019, Suryo filed a wealth report with the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) in which he disclosed Rp 14.4 billion (US$ 94,3458) in assets. The figure is only one fourth of the wealth of his subordinate, Rafael Alun Trisambodo, who has come under public scrutiny after his 20-year-old son, Mario Dandy, was arrested for allegedly assaulting teenager David Ozora.

Through his social media account, Mario had flaunted his family’s lavish lifestyle, including his possession of a Jeep Rubicon car and Harley Davidson bike. The police have seized the Jeep as evidence, as Mario is accused of having changed its license plate before allegedly abducting David.

There is good reason to question how Rafael accumulated his wealth, as well as to scrutinize other tax officers. In 2010, revelations that tax officer Gayus Tambunan had amassed some Rp 100 billion by helping tax evaders shocked the public. In February of last year, former tax office director Angin Prayitno Aji was sentenced to nine years in prison for accepting bribes.

In an effort to prevent corruption within the Taxation Directorate General, the institution’s civil servants have the highest take-home pay in the state bureaucracy. The second- and third-highest take-home earners are officials at the Jakarta administration and the Finance Ministry.

Officials in the executive, legislative and judicial branches are required by law to declare their assets. But the regular wealth report is a formality at best; the KPK has hardly ever gone after a public official for a dubious disclosure. Only state officials caught in the act of corruption have been penalized.

In the case of the Finance Ministry, Sri Mulyani said that over the past five years, all ministry officials had complied with the regulation. The deadline to submit the wealth report this year is March 31, and as of Saturday, Sri Mulyani said, some 19,500 of 33,370 officials had fulfilled their obligations.

Members of the public can access these wealth reports at https://elhkpn.kpk.go.id, but as it stands, it is far too complicated for individuals to assess properly. The Finance Ministry and the KPK should offer a much more user-friendly platform and database.

To fight corruption, activists have demanded that graft laws shift the burden of proof in corruption court trials by requiring that defendants prove their innocence rather than solely obligating prosecutors to produce evidence of guilt. The principle was successful in putting former tax officer Bahasyim Assifie behind bars for money laundering in 2011.

But the House of Representatives has been reluctant to approve any major changes favoring prosecutors. This may be out of concern for the presumption of innocence or may simply be because politicians and their cronies would be more likely to fall prey to stricter corruption laws.

With the country’s corruption perception index at a record low, reforms within the Taxation Directorate General and the state bureaucracy as a whole are urgently needed, both to clean up the institution and to regain the trust of the public – especially taxpayers.