June 20, 2025

SEOUL – “I just gave birth to a baby,” said a woman’s urgent voice over the phone as Hwang Min-sook was about to leave work one winter day.

Hwang urged her to call 119, the medical emergency hotline, but the caller replied, “I can’t do that.” Hwang told her to take a taxi and come to her at Babybox Korea in Gwanak-gu, Seoul.

A few hours later, the woman arrived with her newborn in her arms. The staff suggested she stay overnight and go to the hospital the next morning, but the mother insisted on leaving and did not take her baby. She said she had to clean up the blood and other signs of childbirth before vacating the rented room the next day.

A month later, the woman called again. She explained that the room had been in a redevelopment area where all the residents had already moved out. It was dusty and had no electricity, and she had temporarily borrowed the space to give birth. It was then that Hwang understood what might have caused the newborn’s septicemia.

After that call, the mother never made contact again. Once the infant’s health was restored, the baby was transferred to a child welfare center.

Not everyone can imagine what that mother went through. But Hwang said, “There are many who give birth alone and abandon their babies. The baby box is their last refuge.”

Babybox Korea’s managing director Hwang Min-sook poses for a photograph after an interview. PHOTO: THE KOREA HERALD

A baby box is a facility that allows mothers to safely leave their babies in a protected environment.

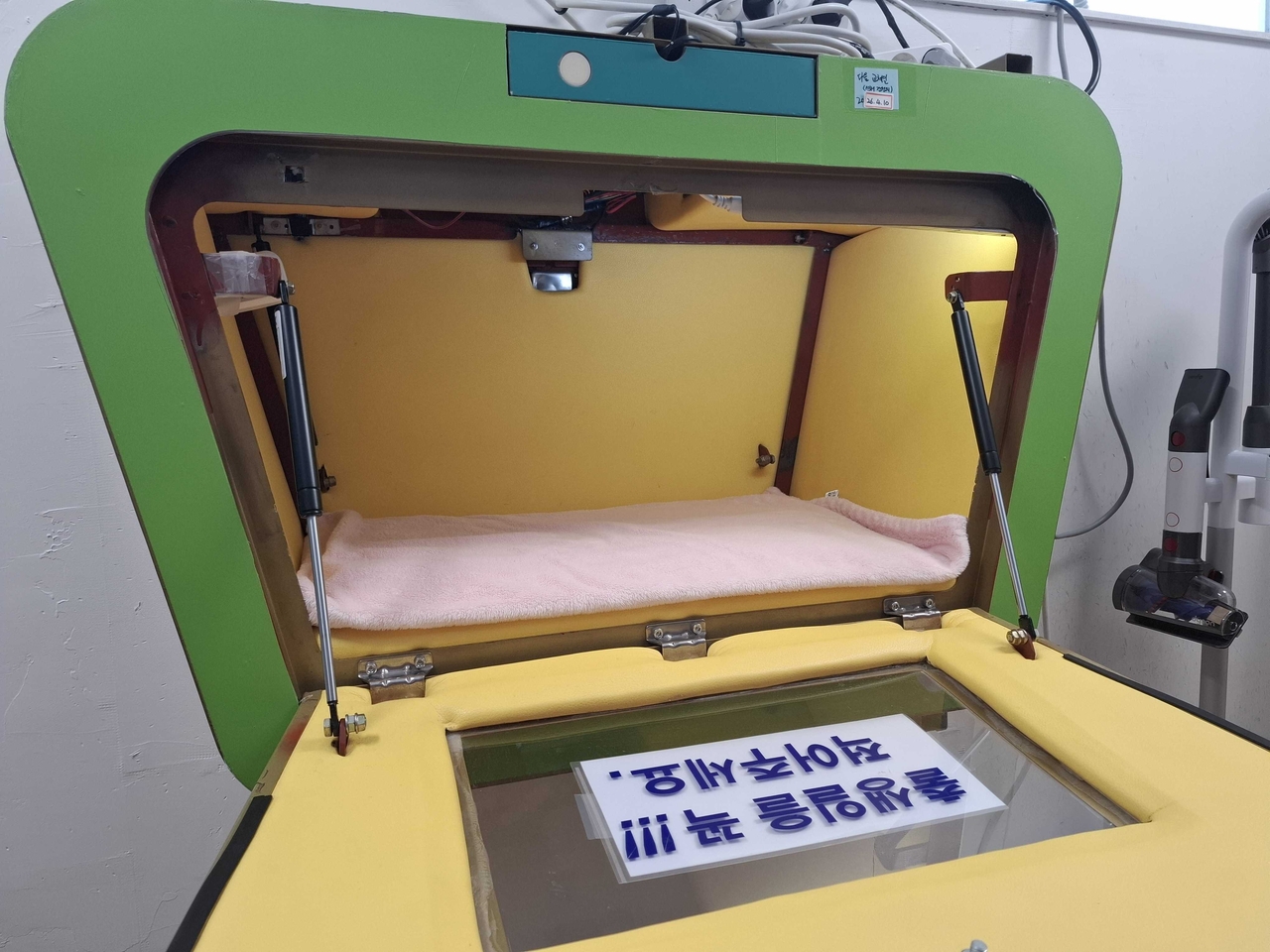

The baby box is installed in front of Jusarang Church, which operates Babybox Korea. Once a baby is placed inside, an alarm alerts the staff, who immediately bring the infant into the care room. PHOTO: THE KOREA HERALD

There are currently two such facilities in South Korea. The one in front of Jusarang Church, which operates Babybox Korea, is the first of its kind.

The baby box was started by the church’s pastor, Lee Jong-rak. One winter night in 2007, he received a phone call at around 3 a.m. A man on the line said he had left a baby in front of the church.

Lee rushed outside and found a baby with Down syndrome lying in a smelly fish box. The infant was cold. He brought the baby inside and began taking care of it.

Word spread that the pastor was caring for a child with disabilities, and soon more babies with various conditions began appearing in front of the church overnight. Fearing that one might die in the cold, he built a box where parents could safely leave their babies. It became the first baby box in the country.

The box was later upgraded with a sensor that triggers an alarm when a baby is placed inside. Staff members, working around the clock in shifts, respond immediately — bringing the baby into care and, when possible, offering counseling to the mothers.

The concept of baby boxes, however, is not unique to South Korea. Similar systems exist around the world for mothers in crisis. Today, baby boxes — under the same or different names — are operated in at least 20 countries, including the United States, Germany, the Czech Republic, Poland and Japan.

In Korea, in May 2014, a second baby box was installed at New Canaan Church in Gunpo, Gyeonggi Province.

A baby box is a designated safe location where infants can be anonymously surrendered. This baby box, operated by Babybox Korea, has a notice with three exclamation points reading, “Please write down the baby’s birthday.” PHOTO: THE KOREA HERALD

Since pastor Lee installed the first baby box outside his church, a total of 2,181 babies have been surrendered as of March this year.

When a baby arrives, the staff at the facility care for the child for up to six months, until the local authorities determine their future. Of the 2,181 babies, 1,693 have been sent to child care centers, 167 have been adopted and 311 have been returned to their mothers. In the remaining 10 cases, records are unavailable.

Hwang explained that when the alarm goes off, the center typically brings the mother inside for counseling and offers any support she might need. “The main goal of counseling is to encourage mothers to raise their babies themselves,” she said, adding that the center provides support for three years, including baby kits, medical costs, legal and housing assistance, and living expenses. All of this is funded by donations.

“The saddest thing is when mothers disappear or don’t give up custody. If mothers don’t relinquish custody, the babies cannot be adopted and must remain in child care centers,” she said.

The number of infants left at the baby box has fluctuated in step with changes to local laws and policies on adoption and support for single mothers with unplanned pregnancies.

Arrivals to the baby box have surged since 2012 when the Act on Special Cases Concerning Adoption took effect, making it illegal to put a child up for adoption without first registering the birth. This made it difficult to give up babies for adoption anonymously.

A major change came last year with the implementation of the anonymous birth system, which allows women to give birth in hospitals without revealing their identity. Still, Babybox Korea saw the arrival of 58 babies last year, Hwang revealed.

Clothes donated for the babies are neatly arranged at Babybox Korea. PHOTO: THE KOREA HERALD

According to Hwang, despite changes in policies and support systems, one powerful force remains unchanged: the social stigma surrounding single motherhood.

Parents with higher levels of education are more likely to oppose their daughters giving birth outside of marriage, fearing it could damage the family’s reputation and social standing, she explained.

Addressing criticism that the baby box makes it too easy for mothers to surrender their babies, she said, “For the mothers who come here, this is the last resort. They come from all over the country, simply trying to save their babies by any means.”

Indicative of the desperation many of these women face, she added that about 13 percent of the mothers who sought help from the center had given birth outside of hospitals.

Mothers receive counseling here. Many of them are still bleeding and cry a lot, according to Hwang. PHOTO: THE KOREA HERALD

Government support for single mothers does exist. There are state-run shelters where single mothers or expecting mothers can stay. Counseling services and food assistance are also offered. But Hwang believes it’s far from sufficient.

According to a comprehensive survey released by the Welfare Ministry in 2023, 249 babies born between 2015 and 2022 died without ever being officially registered.

“When mothers talk to our counselors about entrusting their babies to us, they cry their eyes out. When adoption is decided, they write letters to their babies. Many wrote, ‘I wanted to raise you, but I’m sorry. I was happy for a few days because of you,’” she said.