July 26, 2023

NEW DELHI – In 2021, Mr Bhumenjoy Konsam set up an e-learning business in his home town Imphal, the capital of Manipur state, in north-east India. Business was thriving, thanks to a range of international clients, and things seemed to be on the upswing for the 47-year-old entrepreneur.

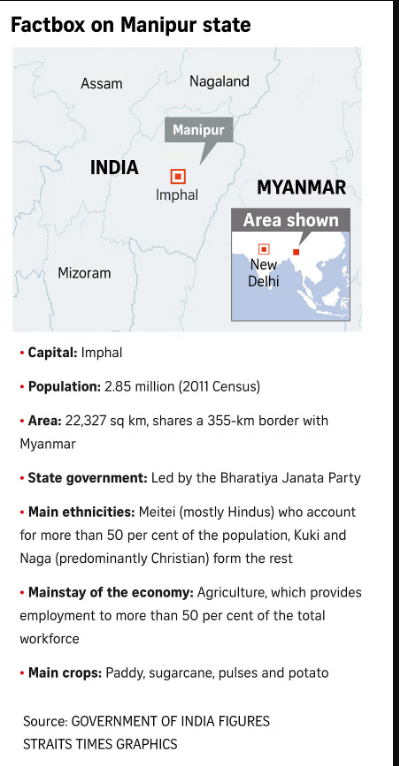

But all this progress came to a grinding halt on May 3, 2023, when the local government imposed a blanket ban on access to the Internet across the state, following ethnic clashes between the majority Meitei and minority Kuki communities.

The goal of the Internet ban was to curb online rumour-mongering and hate speech that risked rendering a tinderbox-like situation even more volatile.

But with no lasting solution in sight – the conflict has since claimed more than 140 lives and displaced around 60,000 people – the state’s three-million-plus people continue to be mostly cut off from the Internet even now. This ban, which has lasted more than 80 days, has been crippling for those like Mr Konsam, whose lives depend on the Internet. On July 8, he finally relocated to Guwahati in the neighbouring state of Assam, where he has rented a flat and hooked himself up to the Internet to try to rebuild his client base and business.

“It has been going on for too long,” said Mr Konsam, who estimated his losses at more than 1.5 million rupees (S$24,300). He petitioned the High Court of Manipur in June, seeking restoration of Internet services in the state.

“Had it been for 10 days or so, one could have adjusted. But a two-month-plus ban is a complete strangulation for those who work online… It’s just like cutting off water for fish,” he said.

Some reprieve finally came on Tuesday, when the government said it would restore broadband Internet access “conditionally, in a liberalised manner”. Mobile Internet and access to social media continue to be prohibited.

The long ban in Manipur has renewed the debate on the cost of such moves in India, which has for five successive years maintained the notorious distinction of imposing more Internet shutdowns than any other nation. Besides paralysing daily life, including through denial of educational and financial services online, the ban has drawn criticism from many who argue that it has allowed the authorities to cover up their failures and evade accountability.

This was the case when a horrific video depicting two Kuki women being paraded naked and groped by a Meitei mob emerged online last Wednesday, more than 75 days after the incident took place on May 4.

A police report was filed on May 18, but arrests were made only after the video was circulated widely and drew widespread condemnation.

This attack was prompted by a message that had gone viral before the Internet ban was imposed. Using a photo of an old honour-killing victim from Delhi, the message falsely claimed the body was that of a Meitei woman who had been raped and killed by Kukis.

A Kuki Christian church in Imphal, Manipur, that was vandalised by a mob during ethnic conflict that has killed at least 140 people. PHOTO: AFP

Acknowledging that “misinformation is a genuine problem that causes real-world harm”, Mr Tanmay Singh, a senior litigation counsel with the Internet Freedom Foundation, said the Internet also happens to be the “prime means of fighting misinformation”.

“It is difficult to fact-check offline,” he added, suggesting the government and civil society members such as fact-checkers and journalists could have countered the fake narrative widely online, had Internet access been available.

In 2020, India’s Supreme Court stated in an order that freedom of speech and expression includes the right to the Internet, and that any restriction on it had to follow “principles of proportionality”. This came in response to a legal challenge to the ban on Internet services in the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir, one that eventually lasted 18 months.

Mr Singh noted that blocking access to “the entirety of Internet services”, instead of targeted closures of channels of misinformation, was a violation of the order.

“Just to flip the switch for the entire state, which has a very large number of people, many of whom are just trying to get through their day using the Internet, is not a proportionate response,” he added.

The court in 2020 had also ruled that indefinite imposition of Internet shutdowns was unconstitutional, following which the government later that year amended rules to specify that an Internet shutdown order can remain in force for a maximum period of 15 days.

But the Manipur government has bypassed this clause by ordering successive bans of five days each.

On June 16, the High Court of Manipur ordered the state government to allow restricted Internet access in certain areas under the control of the authorities, which was followed by another order in July calling on the government to lift the ban partially by allowing Internet access through leased lines and to consider fibre-to-home connections on a “case-to-case basis”.

Mr Konsam had applied to the government on June 30 for an Internet connection at home, but has not heard back. “The Internet may be seen as a security threat, but it is also a means of livelihood for people like me and many others. So the government has to be fair to both sides.”

Meanwhile, Mr Chongtham Victor Singh, a lawyer at the High Court of Manipur, is hopeful that Internet services will be restored fully and soon, including on mobile phones. The 44-year-old had petitioned the Supreme Court in June to seek a reversal of the ban. But he was asked by the court to approach the High Court of Manipur as it was already hearing similar cases.

“We do need to communicate so that we can sort out misunderstandings,” he said.