September 27, 2018

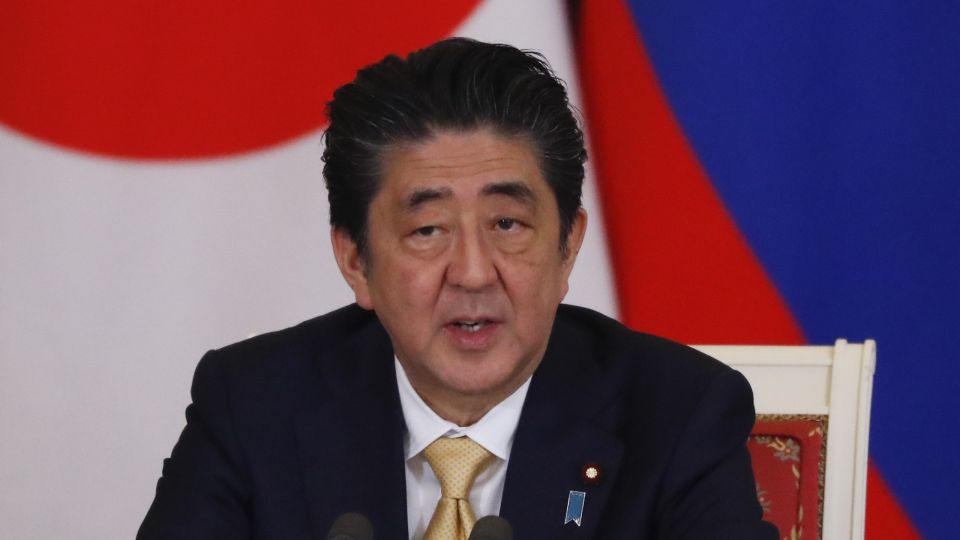

The Bank of Japan could have increasing difficulty steering its monetary policy, as some believe Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is becoming less focused on achieving a 2 percent inflation target.

Members of the BOJ Policy Board are divided, with some wanting to stick to achieving the 2 percent target quickly and others worried about possible side effects on the economy.

Going forward, the divisions could widen further.

Govt’s ‘wide target’

BOJ Gov. Haruhiko Kuroda was asked if the government was losing enthusiasm for the 2 percent target during a press conference after a lecture in Osaka on Tuesday.

He responded, “I don’t think [the BOJ] has a different plan than the government, but the government has set a wider target.”

At a press conference on Sept. 20, Abe said that the objective of the price stability target was “to try to maximize employment, which is the most important issue, by getting closer to the target.”

Abe also emphasized that the employment situation is improving.

In the financial markets, some interpret Abe’s remarks as meaning the status of the 2 percent target has changed.

Risk of acting too late

At a policy meeting at the end of July, the BOJ adjusted its policies in order to brace for lengthening large-scale monetary easing. To stimulate the government bond market, the central bank, in guiding the long-term interest rates to around zero percent, allowed the range of fluctuation of the interest rates to double from between minus 0.1 percent and 0.1 percent.

Minutes of the July meeting released Tuesday show that several members of the Policy Board expressed concerns about the side effects of monetary easing.

One said: “Side effects should be fully considered, and their impact should be mitigated as much as possible. A review should be made to determine if there is room to revise” monetary easing policies.

Long-term monetary easing could worsen the profitability of financial institutions, reducing their management vitality, which could lead to restricted lending and other issues.

In an August lecture, board member Hitoshi Suzuki sounded the alarm, saying that if side effects “became apparent, it could be too late to deal with the risks.”

Others have been more optimistic.

Board member Goshi Kataoka has said, “It does not appear that any particular side effects have occurred.” He has called for additional easing to reach the inflation target.

Board member Yutaka Harada has said that reaching the inflation target quickly deserves more attention than worrying about side effects.

Kuroda’s stance unchanged

Kuroda launched his policy of large-scale monetary easing in the spring of 2013 with the aim of reaching a 2 percent inflation target “in about two years.”

More than five years later, the target has yet to be reached. For example, the consumer price index this year has not even risen 1 percent compared to last year.

If skepticism over the 2 percent target grows, so could worries over possible side effects.

On Tuesday Kuroda said, “My policy stance to achieve the 2 percent target as soon as possible has not changed at all.”

However, many analysts believe it is becoming more difficult for the Policy Board to reach a consensus.