May 19, 2025

DHAKA – Medieval Bengal’s links to the Straits world, a narrow stretch of water connecting to Southeast Asia and beyond, are overlooked. This world saw not only ocean-going vessels, but also coastal and localised traffic which, like riverine transport, has gone largely unrecorded.

Bengali Hindus and Muslims worked in the Straits world as warriors, goldsmiths, fishermen, slaves, interpreters, religious teachers, traders, and diplomats. A minor ‘Bengali’ dynasty of four Turki adventurers, fleeing the turmoil of Bengal’s reunification c. 1352, ruled Samudra Pasai until 1390. An anonymous Portuguese document on Bengal in 1521 references Bengali Muslim shipping. A document from 1522 discusses the Banten-Melaka accord, citing a grandee ‘Bemgar’ (a Portuguese reference to his Bengali origin).

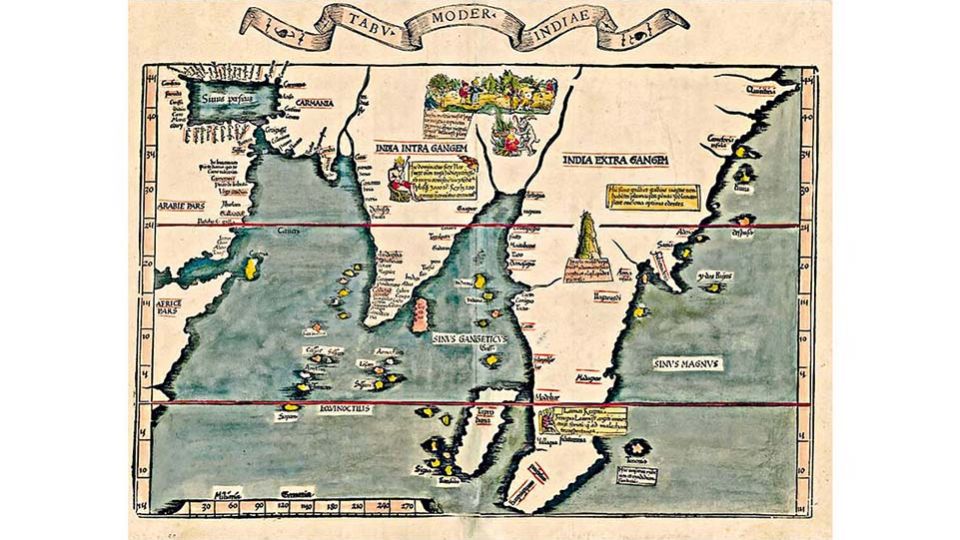

Fries’ map (Image 1) depicts numerous port towns in the southern Bay, but Bengal (lying between India Intra Gangem [India within the Ganges] and India Extra Gangem [India beyond the Ganges]) is unrepresented. It features no port towns, only heathens and devil-worshippers. This is the northern Bay of Bengal—a coast marginal to European shipping. Its geographic fortunes reflect a continuity and uniformity of historical experience, which the following sections will underline.

Northern Bay of Bengal

Spanning Arid and Monsoon Asia, Bengal is climatologically distinctive. Ruled from Laknawati/Pandua/Gaur/Tanda—where Arid Asia ends—its robust mercantile section, the Bengal-Arakan-Burma continuum, begins in Monsoon Asia, in the dense forests and marshes of the southeast. Cultural and economic fulcrums tilted it toward the Straits world rather than the middle Gangetic plain. Physically distinctive with a coast defined by a low-lying tract called bhati, rivers link remote uplands (Image 2). This trans-regional topography (upland/lowland, river/sea) and climate (monsoonal, subtropical to tropical) made it a composite unit for seafaring before the rise of modern navigation.

These quirks dictated sailing conditions. As now, vicious cyclones battered the coast. North-eastern monsoon winds blow between October–November and February, enabling sailings from the east coast and Sri Lanka to Southeast Asia. From May–June until September, monsoon winds aided return journeys. The Straits run was an integral part of this perilous maritime world.

The Straits World

Melaka port-city dominated the fifteenth-century Straits world. Per received history, Melaka rose with the Portuguese conquest of 1511 that inaugurated an age of commerce, along with Achin (1511), Banten (1527), and Johor (1528). This is incorrect. Emerging at a transitional moment in Bay, Straits and Island Southeast Asian history, Melaka dominated the Straits world from its founding in 1402, generating an Asian age of commerce with Ming China’s support. Buddhist religious, diplomatic, and commercial networking was replaced by Islamic networks. Geoff Wade saw cash cropping and commercialisation generating a trade boom, a demand for money, and new common means of exchange. Newly established mints used sophisticated technology; new fiscal systems appeared. The arrival of the Southeast Asian junk, new navigational techniques, prominence of Theravāda Buddhism from Lanka and Bagan, adoption of Islam, and a military revolution were other manifestations. Additional developments included territorial consolidation, the birth of literate administrations and history-writing, the increasing prominence of legal codes, and new links between Southeast and South Asia. Ayutthaya’s (c. 1438) prominence echoed the cosmopolitanism of Melaka and Arakan’s Mrauk U (c. 1431). In 1450, Gaur became the Sultanate’s capital and remained, until its decline in 1575, a primate city with a population estimated at 200,000.

Did Melaka’s rise as a singular prominent intermediary marketplace at the intersection of the Bay of Bengal, South China Sea, and Java Sea regional networks (Image 3) benefit Bengal? John Deyell’s analysis of Bengal’s bullion trends shows 1390–1415 marked by heavy, yet disturbed, bullion inflows; 1416–29 saw the reverse—a net outflow from Bengal, suggesting negative trade balances; 1430–92 saw a moderate but sporadic inflow of silver. From 1493 to 1533 (a period spanning the Sultanate’s later years and Portuguese Melaka’s early years), Bengal saw increasing silver inflows. The Melaka–Bengal trade took off in the 1530s, but was hampered by a customs duty of 8% compared to the usual 6% for other Asian shipping at Melaka. By the sixteenth century’s end, it was again disadvantaged by the imposition of an exit duty for goods destined for Bengal. This forced mariners to explore alternate routes and ports—Achin, Banten, and the Malay Peninsula ports of Kedah, Trang, and Perak.

Sixteenth-Century Bengal

Unlike the fifteenth century, the sixteenth century offers abundant documentation of Bengal’s trade. Sanjay Subrahmanyam noted that the Bengal–Melaka trade was dominated by Klings from the Orissa–Andhra coast rather than by Persians from Bengal, as popularly believed. There were four arcs: the first to Melaka—essentially a textiles-for-cloves trade; the second to the Pegu port of Cosmin (Kusuma); the third to Lanka, Malabar, and the Maldives; and a fourth to Gujarat and the Red Sea, less to the Persian Gulf.

The Malay Annals note that in 1509:

“…there came a ship of the Franks from Goa trading to Malaka: and the Franks perceived how prosperous and well-populated the port was. The people of Malaka for their part came crowding to see what the Franks looked like…and said ‘these are white Bengalis’!”

Obviously, Bengalis were familiar. In 1513, on Melaka captain Rui de Brito’s advice, Melaka’s bendahara Nina Chatu sent a ship to Bengal to ‘give news of us in that land truthfully, so that they might come here without fear.’ In 1516, an official Portuguese expedition was tasked with ‘discovering the Bay of Bengal’. It dispatched João Coelho, who reached Chittagong on a ship owned by a Muslim merchant, Ghulam Ali (Gromalle), a ‘relative of the governor of Chittagong’. Coelho remained there until 1518, when the first Portuguese fleet of three vessels under D. João da Silveira’s command arrived. More squadrons claiming trading rights were dispatched to Gaur and Mrauk U in 1521 and 1534, and Domingo de Seixas was sent from Ayutthaya to Chittagong to secure supplies for Melaka’s constant wars against Achin.

The Melaka–Bengal trade took off c. 1530. Around 1538, seeking help against Sher Shah Suri’s invasion, Mahmud Shah granted João Correa part of Satgaon’s customs revenues. Nuno Fernandes Freire was appointed collector of Chittagong’s customs. By the 1540s, two carreira existed—one each for Chittagong and Satgaon. Pipli entered Portuguese networks around 1560, also as part of the concession trade. By the late 1570s, Portuguese networks re-oriented towards the Coromandel coast, and the Chittagong and Pipli concessions declined. Around 1582, Chittagong came under Arakan. Concessions bypassed Arakan’s meagre trade offerings. Satgaon, attracting the Crown trade, and Hugli after 1580, became hubs.

There were also ‘quasi-informal’ concessions. On 30 April 1559, Bakla’s Paramananda Rai and Viceroy Constantino de Bragança signed a treaty at Goa. Bakla was opened to Portuguese shipping with fixed and low customs duties if the Portuguese discontinued their visits to Chittagong, then under Arakan. In return, Bakla received licences for four ships to trade with Goa, Hormuz, and Melaka. This run, supplemented by stops at the port towns of Sripur and Sandwip, extended this network into smaller ports like Loricoel and Catrabuh. As the formal and informal met at these port towns, religious conversion accelerated. Loricoel got an Augustinian church. Sripur’s Kedar Rai allowed Francis Fernandez to build a church in 1599, giving land and money for the purpose. Around 1599/1600, Bakla’s Pratapaditya allowed the Jesuit Father Fonseca to erect churches and carry out conversions. The first Catholic church of Bengal was built in Ishwaripur with his financial support.

Was this an age of commerce? Did geographic factors aid or hamper trade?

Growth or Decline?

Urban fortunes fluctuated as rivers shifted. Pandua vanished, to be replaced by the first city of Gaur on the interfluve between the Kalindri and Bhagirathi rivers. The Gaur we reference is actually the second city of Gaur. It was damaged in the 1505 earthquake, which affected river courses. Earlier, the Bhagirathi had flowed east of Gaur, but in the second Gaur, the river lay to its west. Devastated by floods, it was finally abandoned in 1575; a plague outbreak was the last straw. Its port Satgaon decayed; Hugli port appeared in 1580. Bengal’s capital shifted to upland Tanda, but fluvial instability generated a west-to-east migration, and upland Bengal’s unstable physical morphology overturned port-capital-hinterland relations. In the southeast, Bakla port-town was destroyed by a cyclone and storm-wave in 1584.

Fortunes fluctuated in the Straits world as well, but for different reasons. Melaka’s rise presaged Singapura’s decline; Melaka’s trading hegemony was challenged by Samudra Pasai and Ayutthaya, and its fall to the Portuguese in 1511 benefited Ayutthaya, Achin, Banten, and Pegu. Banten became an alternative to Melaka. Ayutthaya rose in 1438 at Sukhothai’s expense; the Dutch conquest of Melaka in 1641 benefited Achin and Johor.

Southeast Bengal in the ‘Age of Commerce’

We now revisit Anthony Reid’s ‘Age of Commerce’ thesis insofar as the southeast is concerned. Not only can this age be pushed back into the fifteenth century but, as the sixteenth century also showed decline (hinterland and coastal polities fell concurrently: Ava [1527], Bengal [1538], Pegu [1539], Lan Na [1558], Ayutthaya [1596]), the decline was not confined to the seventeenth century alone as Reid argued.

Moreover, the trajectory of decline varied from region to region, suggesting overland pressures at play. Victor Lieberman saw the seventeenth-century crisis as part of a global trade depression, population decay and political fragmentation in major markets (such as Ming China), accompanied by a decline in prices, a drop in world temperatures (negatively affecting harvests) and decay in world silver supply. Consequently, polities moved away from cash crops and maritime trade to staple crop cultivation. They pursued self-sufficiency, resulting in lost port-cities, de-urbanisation, and political decentralisation. Reid and Lieberman saw mainland Southeast Asia’s interior states—less dependent on maritime trade—expanding and establishing control over coastal rivals. Along with the continuity of long-term developments in core polities such as Burma, Vietnam, and Thailand, smaller mainland Southeast Asian states on the periphery experienced crisis and decline in response to core state expansion. While cores expanded, centralised and defined themselves and their cultures, smaller fringe polities like Lan Na and Cambodia declined and got lost in the shadow of their expansive neighbours.

This happened in Bengal as the west strengthened at the southeast’s expense. Fluvial shifts, fragmenting the southeast with new channels, precipitated a crisis with swampy marshlands and recurring plagues. New agrarian frontiers opened up with rice-growing areas, and revenues rose. But slave raids and desertion offset these positive trends. The southeast’s physical and economic integrity was predicated on the Bengal–Arakan networking, but now the sea route to Arakan was abandoned. Trade through the uplands to Ava, Yunnan, and China decayed. Assam, Tripura, and Manipur reported an escalation in animal pestilences and smallpox epidemics. Smallpox, allegorical or real, was severe. In Tripura, Dharma Manikya (1462), Dhanya Manikya and Vijay Manikya (dates unknown), and Chatra Manikya (1670s) died of the disease. Smallpox is recorded for 1574, 1637, and 1768 in the Ahom state, and in Manipur for 1520, 1531, 1541, 1581, 1651, 1672, 1685, and 1699.

Paradoxically, as river shifts, raids and disease undermined local communities and dislocated shipping and trade, mobility increased. One reason was the famines from 1630–35 in southeast Bengal and lower Burma. Glanius’ testimony, which contemporary Persian records corroborate, noted a particularly severe one between 1662 and 1666, which spread to Assam. The slave trade increased and Pipli, Sagor, Sandwip, Chittagong, Mrauk U, Kedah, Johor, and Achin became slave ports. Achin was a premier slave market where ships from Bengal, Borneo, and Macassar brought slaves in the 1660s. Mrauk U became another market with raided slaves from Bengal and forced converts. Sebastian Manrique claimed he converted, on average, around 2,000 Bengali Hindu and Muslim peasants every year at Dianga, a fishing village adjoining Chittagong. Another ‘slave’ port, Angarcale, brought in similar numbers.

Arakan’s slave trade was both domestic and international. It had entered this trade not only through the compulsions of international trade but also because of its chronic shortage of manpower. While initially used for clearing jungles and as agriculturists for additional rice cultivation, mercenaries and skilled craftsmen were increasingly abducted for resettlement. Mughal chronicler Shihabuddin Talish observed that “[o]nly the Feringi pirates sold their prisoners. But the Maghs employed all their captives in agriculture and other kinds of service”.

Resilience Against Adversity: The Melaka Factor

The northern Bay of the seventeenth century saw Portuguese power decaying. Per Subrahmanyam, after the Dutch siege of 1606, Melaka’s customs revenues fell steadily; by 1620 they totalled 18,000,000 reis against 27,000,000 in 1606. Its fortifications were in disarray, and few fighting men remained to defend the city. This dismal picture was exacerbated by expulsion from Sandwip in 1602, from Chittagong and Dianga in 1607, and from Sandwip again in 1617. Felipe de Brito e Nicote, leader of a small Portuguese commercial outpost in Syriam, was killed by the Mon Burmese in 1613. To the Estado, this was a disaster, for Syriam was helping Melaka to control trade flows that were passing into ports outside the Estado’s direct control—alternate ports like Perak, Kedah, Trang, Ujangselang, and Mergui. The Portuguese lost in the west when Emperor Shah Jahan expelled them from Hugli and Hijli in 1632 and 1635. Bocarro’s Livro das Plantas lamented the end of the Bay trade in the 1630s:

…the great Bay of Bengala, and Pegu, where…we once had great settlements of Portuguese…all of them came to an end with great destruction and devastation, and hence today one only navigates to the port of Orixa in the kingdom of Bengala (Pipli), where there is a Portuguese captain appointed by the viceroy only in order to treat with the Moorish vassals of the Mogor, to whom the port belongs…but he has nothing else there, not even a house, save some made of straw…

I end with a question. Did the Melaka factor ultimately destroy southeast Bengal? The southeast eventually recovered and retained the maritime outlet of Chittagong. But despite the founding of Calcutta port after 1690, western Bengal became a hinterland region, and the sea receded in popular imagination.

This also brings us to the question of resilience. The southeast’s chequered career was linked not so much to Melaka, but to Arakan. When Arakan surrendered to Mughal forces in 1666, it lost a port crucial to its survival—Chittagong. The Bengal nawabs recovered Chittagong in 1729 as a vastly reduced commercial asset and ceded it to the East India Company in 1793. Boats from Bassein, Rangoon, and Martaban made annual voyages, exchanging Burmese rice and teakwood for cloth, but Chittagong’s cloth industry decayed when European companies sent textiles to be ‘finished’ in western Bengal. Commercially unsustainable and devoid of trade goods, Joseph Cordier (1823) saw it as a declining mart-town with 12,000 people, now exporting only rice and salt. Yet, trade persisted. Chittagong’s deepwater harbour enabled commerce with Jugdia, Srirampur, Dhaka, Sylhet, and Goalpara. Tamil Muslim shipping from Penang called there in 1838. Howard Malcolm (1836) saw at Chittagong around 300 vessels of between 40 to 100 tons, including “several large Maldivian boats of incredible construction”, indicating networks into the central Indian Ocean. Given this resilience, the port was reorganised in 1887 and in 1928 was declared a ‘Major Port’ of British India. Today, its shipping tonnage far exceeds that of Kolkata.

Rila Mukherjee is a retired Professor of History at the University of Hyderabad in India, specialising in the history of the Bay world.