December 22, 2025

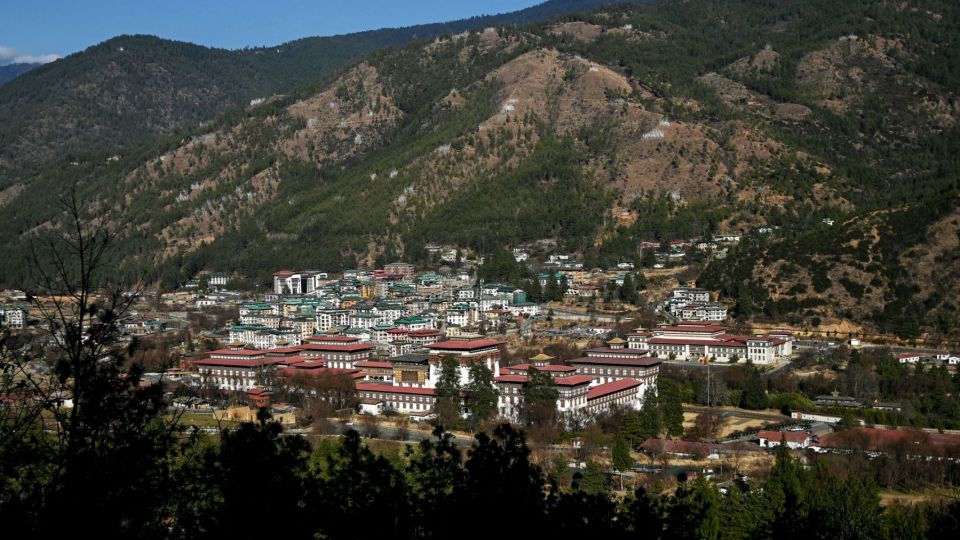

THIMPHU – Bhutan will require an estimated USD 20.49 billion in climate finance between 2020 and 2050 to cope with escalating climate risks, far more than it is currently receiving, according to a new regional study assessing climate finance needs, flows, and gaps across the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH).

The study states that Bhutan faces a combination of high climate vulnerability and limited readiness to respond.

The country is increasingly exposed to biodiversity loss, habitat degradation, rising temperatures, heightened disease risks and disruptions to hydropower generation linked to changing water availability.

Under the ND-GAIN Index, Bhutan has a vulnerability score of 0.55 and a readiness score of 0.21, pointing to mounting pressure on systems that underpin livelihoods and economic stability.

The study, conducted by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), aims to provide policymakers and investors with evidence on where climate finance is falling short and how resources could be more effectively directed to mountain countries such as Bhutan.

The scale of the financial challenge is huge.

Bhutan’s annual per capita climate finance requirement is estimated at USD 2,126.5 –equivalent to 57 percent of per capita gross domestic product and vastly exceeding the United Nations Environment Programme’s benchmark of 2.5 percent for lower-middle-income countries.

Yet actual climate finance flows between 2018 and 2021 amounted to only USD 724 million, with only USD 38.9 million disbursed during that period.

Climate finance entering Bhutan is almost evenly split between adaptation (50.5 percent) and mitigation (49.1 percent).

However, the report shows that adaptation needs overwhelmingly dominate in the long term. Between 2021 and 2050, country’s adaptation finance requirement alone is estimated at USD 14 billion, accounting for nearly 94 percent of total climate finance needs.

Human settlements and climate-smart cities emerge as the top adaptation priority, representing nearly half of the required investment. This is followed by water systems, agriculture and livestock, forests and biodiversity, energy, and health.

Despite these needs, actual adaptation flows remain limited, with USD 39.1 million committed and USD 38.1M disbursed between 2018 and 2021.

On the mitigation side, Bhutan will require around USD 6.5B between 2021 and 2035. More than 90 percent of this is needed for surface transport, reflecting the challenge of decarbonising mobility in a mountainous country where transport costs and emissions remain high.

The report also highlights Bhutan’s reliance on external public finance.

The main sources of climate finance are the International Development Association (39 percent), the Asian Development Bank (26 percent), and the Global Environment Facility (22 percent). Loans account for over 60 percent of climate finance, compared to 38.9 percent in grants, raising concerns about long-term fiscal sustainability.

To address these gaps, the report recommends scaling up nature-based solutions by leveraging country’s constitutional forest cover mandate and carbon-negative status.

It also calls for strengthening private sector investment through blended finance, concessional credit, and risk-sharing instruments, particularly for green tourism, climate-smart agriculture, and clean energy value chains. Unlocking innovative finance, including REDD+ results-based payments and readiness for Article 6 carbon markets, and advancing a national green taxonomy are also highlighted as priorities.

While the findings for Bhutan are striking, the report places them within a much larger regional crisis unfolding across the HKH. The HKH region—spanning Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, India, Bhutan, Myanmar, and China—faces a uniquely severe climate adaptation burden that far exceeds global averages.

According to the report, the region will require a projected USD 12.05 trillion by 2050 to meet adaptation needs until 2050 and mitigation requirements until 2035, with an annual financing requirement of about USD 768.68B. Although India and China account for more than 92 percent of this total, smaller and poorer mountain countries face the greatest strain relative to the size of their economies.

Dr Pema Gyamtsho (PhD), Director General of ICIMOD, said the findings should serve as a wake-up call.“The HKH mountains face the twin challenges of extreme vulnerability and limited resources.”

He said that only concrete, transformative strategies and stronger access to global and diverse forms of public and private finance can guarantee building the resilience needed to secure the region’s future.

Karma Tshering, Secretary of the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, said that despite Bhutan’s carbon-negative status, the country continues to shoulder rising adaptation costs. “Investing in mountains is no longer optional; it is essential for the stability of the region and the planet.”

The report concludes that without improved access to existing climate funds, innovative financing mechanisms, and greater public spending targeted at mountains and environmentally sensitive areas, both Bhutan and the wider HKH region risk falling further behind as climate impacts intensify.