March 31, 2023

MANILA, Philippines — Asserting the need to arrest a suspect or an accused, the International Criminal Court (ICC) said “failure to execute arrest warrants breeds a climate of impunity.”

This, as the continued elusiveness of a suspect or accused in horrendous crimes undermines the collection and preservation of evidence and the safety and wellbeing of possible witnesses and victims, the ICC said.

“It means that he or she might be free to continue committing crimes”—one of the reasons that an arrest warrant is issued once judges are satisfied that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the suspect has committed a crime within the jurisdiction of the ICC.

As the court stressed, there are challenges that the ICC faces in securing the arrest and surrender of a suspect, especially since it does not have its own enforcement mechanism and there are recurring instances of non-compliance with requests for execution of arrest warrants.

So in the Philippines, even if the ICC rejected the government’s request to suspend the investigation into crimes against humanity charges in relation to Rodrigo Duterte’s bloodthirsty anti-drug campaign and President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s statement that the Philippines will disengage with the ICC, justice for victims could remain out of reach.

ICC decision

Last Monday (March 27), the ICC Appeals Chamber rejected the request of the Philippines for “suspensive effect” of the decision of the court’s Pre-Trial Chamber I, which authorized the resumption of the investigation into killings committed under Duterte’s anti-drug campaign last Jan. 26.

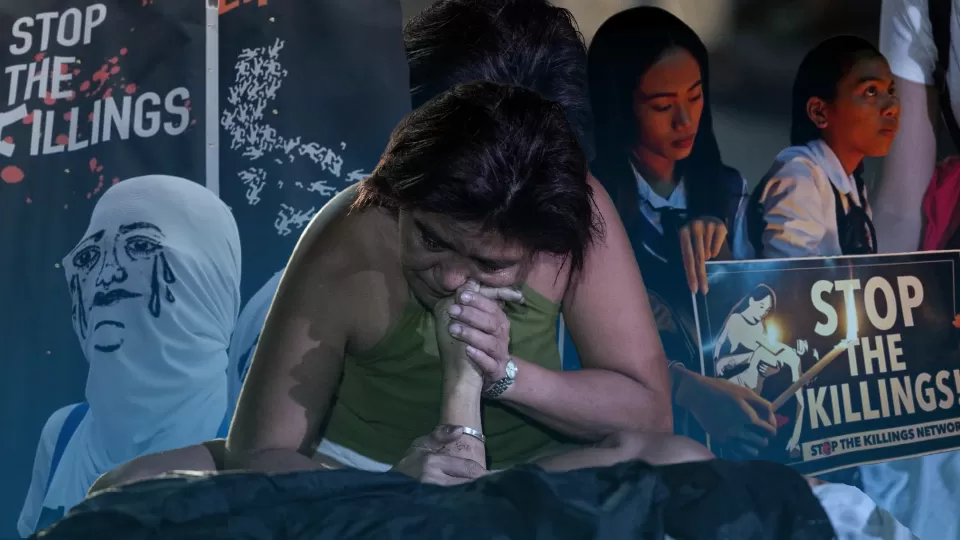

The Philippine government, through the Philippine National Police, acknowledged more than 6,000 deaths during the enforcement of Duterte’s all-out war on drugs. But human rights groups estimate that the number of deaths could be at least four times the government numbers, most of them civilians killed in street executions, home invasions and by vigilantes in connection with Duterte’s aim to eradicate the drug menace.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Most civilians killed in the anti-drug campaign were tagged as “nanlaban” or fought back police during raids on their homes. Many others were just found dead on the streets.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

As stressed by the ICC in its decision, the Philippine government appeal referred to “far-reaching and inimical consequences or implications of the ICC Prosecutor’s activities on suspects, witnesses and victims.”

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

But it “failed to explain what those implications might be and how the Prosecutor’s investigation would result in consequences that the (Philippines’) Office of the Solicitor General claimed could not be corrected.”

The decision was welcomed by the National Union of People’s Lawyers (NUPL), which stressed that “it is all systems go for the ICC prosecutor’s investigation into the Philippines war on drugs, and all victims should be able to participate in the proceedings.”

“We are reassured by the decision of the Appeals Chamber,” said lawyer Cristina Conti, NUPL-Metro Manila secretary general and assisting counsel for Rise Up for Life and for Rights, a group of relatives of victims of Duterte’s bloody anti-drug campaign.

However, Marcos, who once stressed non-cooperation with the Tribunal, said the government will now officially disengage from any contact and communication with the ICC, stressing that it would no longer appeal the ICC’s decision.

“We don’t have a next move. That ends all our involvement with the ICC […] and there is, in our view, nothing more that we can do in the government. So, at this point, we essentially are disengaging from any contact, from any communication with the ICC,” he said.

Marcos’ decision, Prof. Maria Ela Atienza said, “may be consistent with his alliance with the Dutertes and other key figures in the previous administration.” Duterte’s daughter, Sara, and Marcos were in tandem in the 2022 elections.

Atienza, a political science professor at the University of the Philippines Diliman, told INQUIRER.net that the President’s decision to disengage “will hurt the direction of foreign policy under his administration.”

This, as she stressed that the government, since Marcos took office, has focused on re-engaging traditional allies and making the country visible again in regional and international organizations and meetings.

“The President’s latest statement about disengaging from communicating with the ICC will be a big blow to his statements about transparency and accountability,” she said, stressing that “it shows weakness and lack of independence as he is incapable of damaging relations with the Dutertes and other allies who served in the past administration.”

Implications

She said if the government will really disengage with the ICC, the call for justice by victims’ families will have to be dealt with domestically through the justice system, essentially putting victims at a disadvantage.

However, it is not the endgame, Atienza said, stressing that “victims’ families can still network with human rights groups here and abroad, as well as countries supportive of ICC processes.”

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

“These countries can potentially put pressure on the Philippines in terms of making aid and loans conditional if human rights cases are not resolved, either through the ICC or through a more efficient and independent Philippine justice system,” she said.

But what if the Philippines insists on its non-cooperation with the ICC even with the existence of a Supreme Court decision which stated that the country should still cooperate in ICC proceedings for the obligations it has incurred as a member?

As the ICC said, its Assembly of States Parties (ASP) has adopted a series of resolutions on cooperation, underscoring that the failure to execute cooperation requests “hampers the Court’s fulfillment of its mandate,” especially in arrest and surrender.

“The Registry and the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) have developed long standing cooperation on the execution of arrest warrants, building on the OTP’s extensive knowledge of the situations it investigates and the networks available to both the OTP and the Registry,” the ICC said.

According to the ICC website, the Registry is one of its four organs and is responsible for the non-judicial aspects of the administration and servicing of the Tribunal: “All the tasks performed by the Registry are in clear support of the Court’s strategic goals.”

It was stressed that in 2016, an internal ICC Arrest Working Group was set up to formalize the cooperation and enhance synergies and information-sharing on tracking, and on the judicial and operational phases of the execution of arrest warrants.

But why is arresting a suspect important?

No trials in absentia

Article 63 of the Rome Statute provides that proceedings before the Tribunal take place in the presence of the person, that is, the suspect at the pre-trial stage, and the accused person, after the confirmation of charges.

To issue a warrant, the ICC judges must be satisfied that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the suspect has committed a crime within its jurisdiction. They issue a warrant of arrest to make certain that the person appears during trial.

As an alternative, a summons to appear may be issued when there are reasonable grounds to believe that the suspect will appear voluntarily before the ICC. Nevertheless, restrictions on the person’s liberty (other than detention) may be imposed based on Article 58(7) of the Statute.

However, without arrests, the ICC process cannot take place, the judges of the ICC cannot make a determination of guilt or innocence and victims cannot be heard. “Timely arrests also mean a more efficient use of resources,” the ICC said.

The ICC said it has jurisdiction over individuals who bear criminal responsibility for the most serious crimes of concern to the international community: war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and the crime of aggression.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Once an arrest warrant is issued, the Registry is responsible for transmitting the arrest warrant and requests for arrest and surrender to the relevant State(s), in consultation and coordination with the OTP.

The problem, however, is that it is not easy.

Big challenge

The New York-based Human Rights Watch said “securing arrests is one of the ICC’s most difficult challenges” because “without its own police force, the Court must rely on states and the international community to assist in arrests.”

Based on ICC data, before the arrest warrant against Russian dictator Vladimir Putin was issued this year, “15 persons for whom the Tribunal has issued warrants of arrest remain at large.”

It said “some of these arrest warrants were issued by the ICC over a decade ago” and that based on the OTP’s investigations, there are reasonable grounds to believe that some of the most serious crimes proscribed by the Rome Statute were committed by those persons.

These arrest warrants relate to crimes allegedly committed in six ICC situation countries: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Darfur (Sudan), Kenya, Libya, and Côte d’Ivoire, the ICC said.

These suspects, as a whole, are sought for a total of 206 counts: 87 counts of crimes against humanity, 116 counts of war crimes and three counts of genocide, in addition to 13 counts of offenses against the administration of justice, as provided in Article 70 of the Statute.

The ICC said crimes proscribed by the Rome Statute rarely occur in a vacuum; they arise in a context of large-scale criminality, such as transnational organized crime, terrorism, trafficking, corruption or financial crimes.

“Typically, most of the crimes under the Statute are perpetrated – through, for example, planning, financing or devising strategies – by persons at the highest political or military level or by other leaders, or members of or persons associated with organized organizations,” the court said.

Ways to secure arrest

As stressed by the ICC, “greater consistency in the support provided by States Parties for the execution of the warrants and greater information sharing are two easily identifiable areas where progress can be achieved.”

This, as States Parties to the Rome Statute have an obligation to cooperate fully with the ICC, as provided in Article 86, and to ensure that there are procedures available under their national law to execute all cooperation requests from the Court.

Likewise, States may be obliged to cooperate with the ICC by virtue of United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions referring situations to the ICC. This applies also to requests for arrest and surrender from the ICC.

As explained by the Tribunal, the ICC reports yearly to the ASP, the UNSC and the United Nations General Assembly on the status of the execution of arrest warrants. The issue is raised in international fora and in the course of bilateral meetings.

Systematic reminders of arrest warrants are sent to States through the relevant channels, for instance when suspects travel abroad. If a State fails to comply with a request to cooperate, the Registry or the OTP might refer the matter to the relevant Pre-Trial Chamber, which in turn may refer a State’s failure to comply with the ASP or, where the UNSC referred the matter to the Court, to the UNSC.

Non-State Parties have no obligation under the Statute to cooperate with the Court but they are encouraged to do so. “In fact, some of them have played an active role in previous surrender operations.”

However, when the UNSC triggers the Court’s jurisdiction over a given situation, the duty to cooperate binds the relevant UN Member States, regardless of whether they are a State Party to the Rome Statute.

For instance, when the UNSC referred the situations in Darfur (Sudan) and Libya to the ICC, the UNSC imposed an obligation on those two States to cooperate. It also urged all other States to cooperate fully with the Tribunal.

Limited movement

Atienza stressed that “the ICC has limited enforcement powers.”

However, she said if the Tribunal decides to continue its investigation even without the cooperation of the Philippine government and warrants of arrest are issued, “this can limit the movement of these people.”

They may be safe in their own countries or in allied countries but not necessarily in other countries which are members of the ICC or supportive of the ICC, she said.

She stressed that “if certain Filipino personalities are declared guilty, this is also an indictment on the Philippine government and its failure to protect its citizens, possibly leading to a further loss in international standing and credibility.”

HRW said at least 13 ICC suspects have been arrested to date, but arrests can take time, specifically where those sought are high-ranking government officials.

Likewise, Conti said whoever will be identified as the most responsible for crimes against humanity in the Philippines could be safe from being arrested as long as he or she stays in the country where the government already expressed non-cooperation.

However, “a lot of things can change,” Conti said, referring to the political climate that could change, especially every six years, when Filipinos elect a new president to lead the Philippines.