June 17, 2022

HONG KONG – Hong Kong’s native pop music genre is seeing a resurgence, but in a form unlike its original incarnation. Faye Bradley reports.

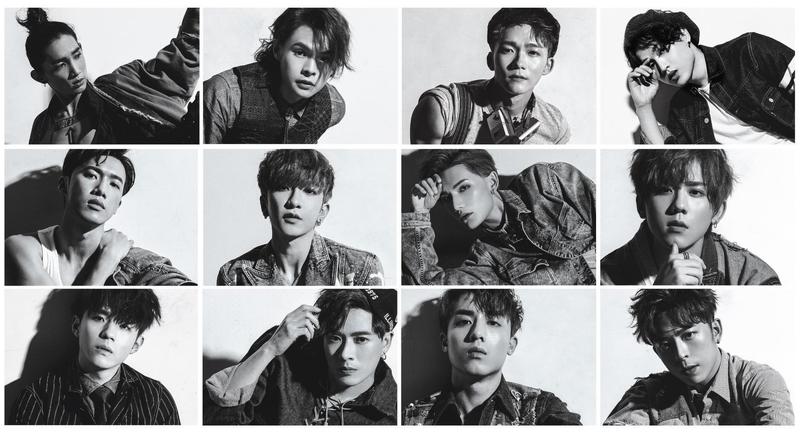

Mirror’s citywide presence is unmissable. Plastered across billboards, buses and MTR stations, the 12-strong group has earned a cult following and plays to sold-out concerts. Having debuted in November 2018, Hong Kong’s hottest boy band has spawned a new generation of fans of Cantopop — a musical genre that had lost some of its glory since peaking more than two decades ago, partly due to competition from Mandopop, K-pop and J-pop. Mirror made Cantopop cool again.

But how did it all begin?

Before the birth of the genre in the 1970s, Cantonese opera and English-language pop were the mainstays of the Hong Kong music scene. Sam Hui Koon-kit, regarded as “the Father of Cantopop”, pioneered the use of vernacular Cantonese in lyrics about people’s everyday travails. This in turn helped shape a “cultural identity built on a shared language and way of life among so-called ‘common people’ in Hong Kong”, according to Stella Lau, senior manager of Learning and Engagement at the Hong Kong Palace Museum.

In 2019, Lau gave a talk at the Xiqu Centre on the evolution of Cantopop. The lecture also touched on the relationship between the local recording industry and mainstream and indie music, as well as the transformation of Hong Kong’s pop music culture in the digital era.

“The second social function of Cantopop is evidenced by a rich repertoire of Cantonese songs that conjure up memories of the wave of emigration … in the 1980s and ’90s,” Lau continues, adding that pop culture serves as a source of collective identity in Hong Kong.

Cantopop’s icons — Danny Chan Pak-keung, Alan Tam Wing-lun, Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing and Anita Mui Yim-fong — ruled in the 1980s and early ’90s, often regarded as the genre’s golden age. By the mid-’90s, however, the city’s musicians were facing stiff competition from other parts of Asia. In 2003, the untimely deaths of Cheung and Mui spelled the end of the first wave of Cantopop — Chan having also died prematurely a decade earlier.

The versatility and stage presence of iconic singer-actors Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing (left) and Anita Mui Yim-fong defined the golden era of Cantopop music, spanning the 1980s and early ‘90s. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Rise and fall

Hong Kong’s return to the motherland in 1997 more or less coincided with the growth of digital communication. Compared with the 1970s and ’80s — when Cantopop ballads would satisfy people’s relatively uncomplicated needs in music — the ’90s were a more questing time, and also more open to outside influences. The rise of the internet opened music fans up to a broader choice of artists globally. Suddenly, Cantopop had become more niche than mainstream.

Many Hong Kong artists switched to singing in Mandarin, but by that time, the phenomenal growth of Japanese and Korean music markets had already begun. Compared with Cantopop’s golden age, the bar for Asian pop artists is set far higher today. The sheer number of fans certain Korean and Japanese bands have outside their home countries was inconceivable in the last century. Today the music scene in Hong Kong is part of a pan-Asian landscape.

The internet revolution hasn’t spelled only doom and gloom for Hong Kong musicians though. YouTube and Facebook provide platforms for showcasing new work before a mass audience without financial risk — and as with overseas musicians like Justin Bieber, offer the chance to be discovered by industry bigwigs.

According to the Hong Kong Palace Museum’s Lau, the internet has also enabled Cantopop to diversify. “Social media and crowdfunding platforms have helped nonmainstream musicians cultivate their niche markets and sustain themselves without the support of major record companies,” she notes. While such musicians may not be as rich or famous as their golden-era counterparts, they can appreciate their own higher degree of autonomy. “Independent Cantopop musicians have relative freedom in conveying their sentiments toward society … compared with mainstream artists who are still, to a large extent, constrained by the protocols of traditional media and major record companies.” The latter, adds Lau, continue to prioritize commercial considerations over creativity.

Jacky Cheung Hok-yau is considered one among the “Four Heavenly Kings” ruling the Hong Kong Cantopop scene in the 1990s. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Diverse city

Angela Hui Ching-wan grew up listening to such stalwarts as Eason Chan Yik-shun, Joey Yung Cho-yee and Kay Tse On-kay — and found fame after posting singing videos on YouTube. Having signed with Emperor Entertainment Group while still in secondary school, Hui made her debut in 2010.

Hui feels there’s reason to be optimistic about the future of Cantopop. “In the early 2000s, people still liked listening to love ballads. Today’s Cantopop singers have their own unique identity, with more external influences like K-hip-hop, which can be integrated into Cantopop songs. … Many different types of audiences can now enjoy the genre.”

Pakho Chau, who got his start in 2007, says promotional strategies were simpler back then as there were fewer ways to reach audiences. “These days, we have so many platforms for promotions, and fans can get to know their idols on a more personal level,” he says. “It’s actually a good thing for audiences and artists, who have better communication.”

Agreeing with Hui, Chau notes that Cantopop’s newfound diversity is effecting a general uplift in standards, saying it “opens doors for independent musicians, singers and bands”. At the same time, he considers the ’90s to be Cantopop’s most interesting period to date: back when the “Four Heavenly Kings” of Hong Kong— Andy Lau Tak-wah, Jacky Cheung Hok-yau, Leon Lai Ming and Aaron Kwok Fu-shing — reigned supreme.

Hong Kong’s homegrown Cantopop boy band Mirror is credited with reviving local interest in the music genre. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Celebrating Cantopop

Many Hong Kong people remain nostalgic for Cantopop’s golden era. In July last year, the Hong Kong Heritage Museum opened a new permanent exhibition of local popular culture titled Hong Kong Pop 60+. The showcase features such golden-era Cantopop artifacts as a Sam Hui platinum disc, and stage costumes worn by Anita Mui, Leslie Cheung and Roman Tam Pak-sin.

“Exhibitions related to the soundscape and visual representation of legendary Cantopop icons can be organized in the future to educate people from all walks of life about this important aspect of local popular culture, which forms part of Hong Kong identity,” Lau says. She hopes some of the local universities will consider including the history of Cantopop in their Hong Kong cultural studies programs.

Canto Cocktail, a digital commission by M+ museum, explores online creative practices at the intersection of visual culture and technology. The karaoke generator uses algorithms to compose medleys based on excerpts of 120 Cantopop songs. Local artist Henry Chu Lik-hang is the brains behind the project, which he says “reflects the increased use of machines for making music, and hints at a future when computers can be creators rather than just tools”. Having grown up on Cantopop in TV drama theme songs, on the radio and in karaoke, Chu says he finds comfort in the AI-created melodies.

The first wave of Cantopop may have ended, but — as Mirror’s success shows — the genre is making a comeback in a more modern form. “I believe that as long as there’s an audience for (Cantopop), there will be people making it,” says Pakho Chau.

Affirms Chu: “I see new generations of songwriters, performers and groups with a love for Cantopop that will never change. We all know that nothing can replace Cantopop.”