April 7, 2022

MANILA — It was in 2021 when President Rodrigo Duterte said that while it’s easy to promise an end to hunger, the path to fulfilling it was not paved like an expressway.

Duterte said this a year after signing Executive Order No. 101 that created the Inter-Agency Task Force on Zero Hunger (IATF-ZH) to address the reasons people go hungry.

The IATF–ZH was asked to work on a National Food Policy (NFP) as Duterte recognized that hunger, and other problems, continued to be serious concerns.

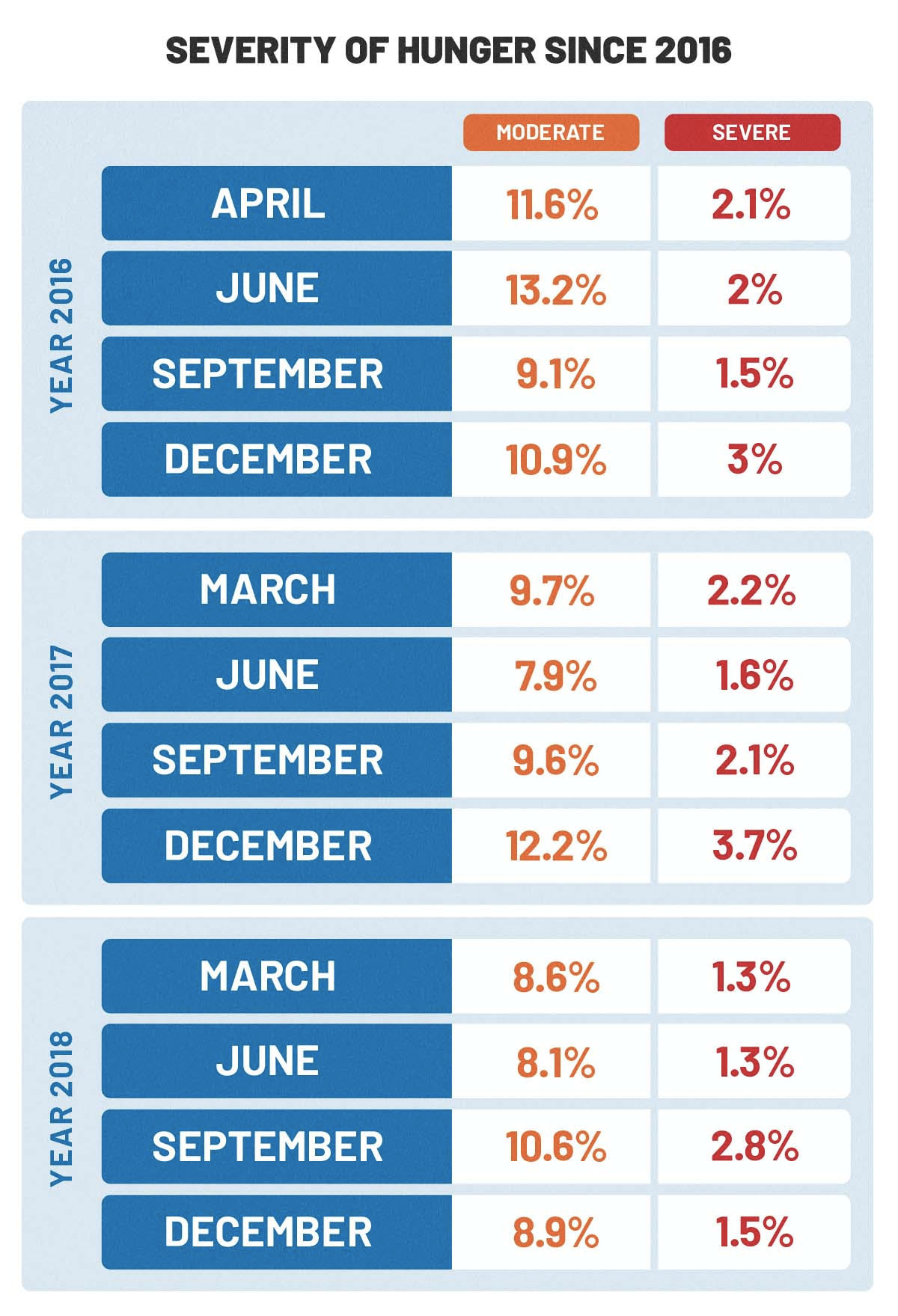

This, as the Social Weather Stations (SWS) revealed in late 2019 (Q4) that 8.8 percent—or 2.1 million—of households experienced hunger—7.3 percent and 1.5 percent had moderate and severe hunger.

It was a 0.3 percent fall from the 9.1 percent—or 2.3 million—households in third quarter 2019—7.4 percent experienced moderate hunger while 1.7 percent had severe hunger.

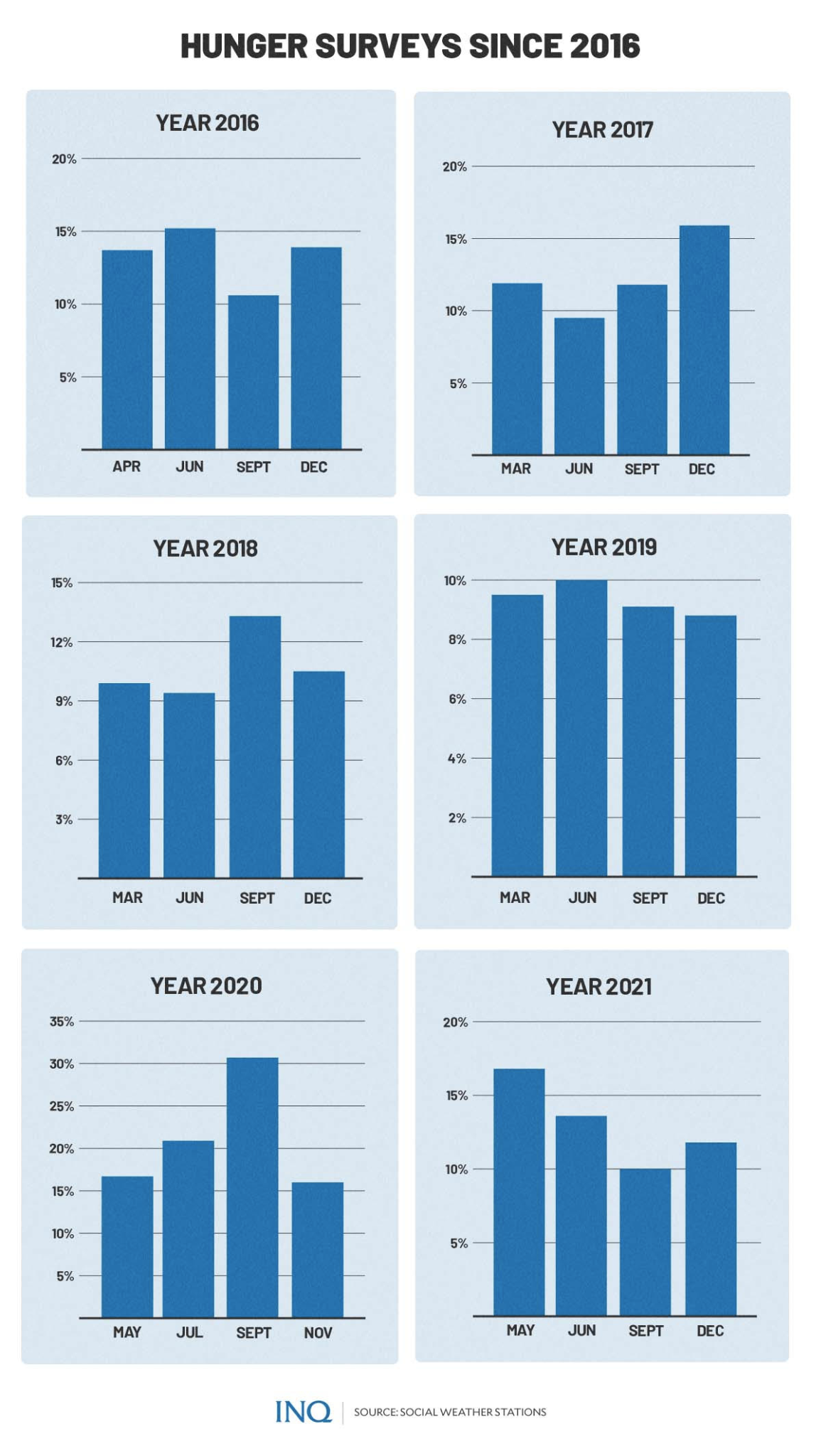

However, as COVID-19 lockdowns brought an economic standstill, hunger hit 30.7 percent of households in third quarter of 2020–22 percent with moderate hunger and 8.7 percent with severe hunger.

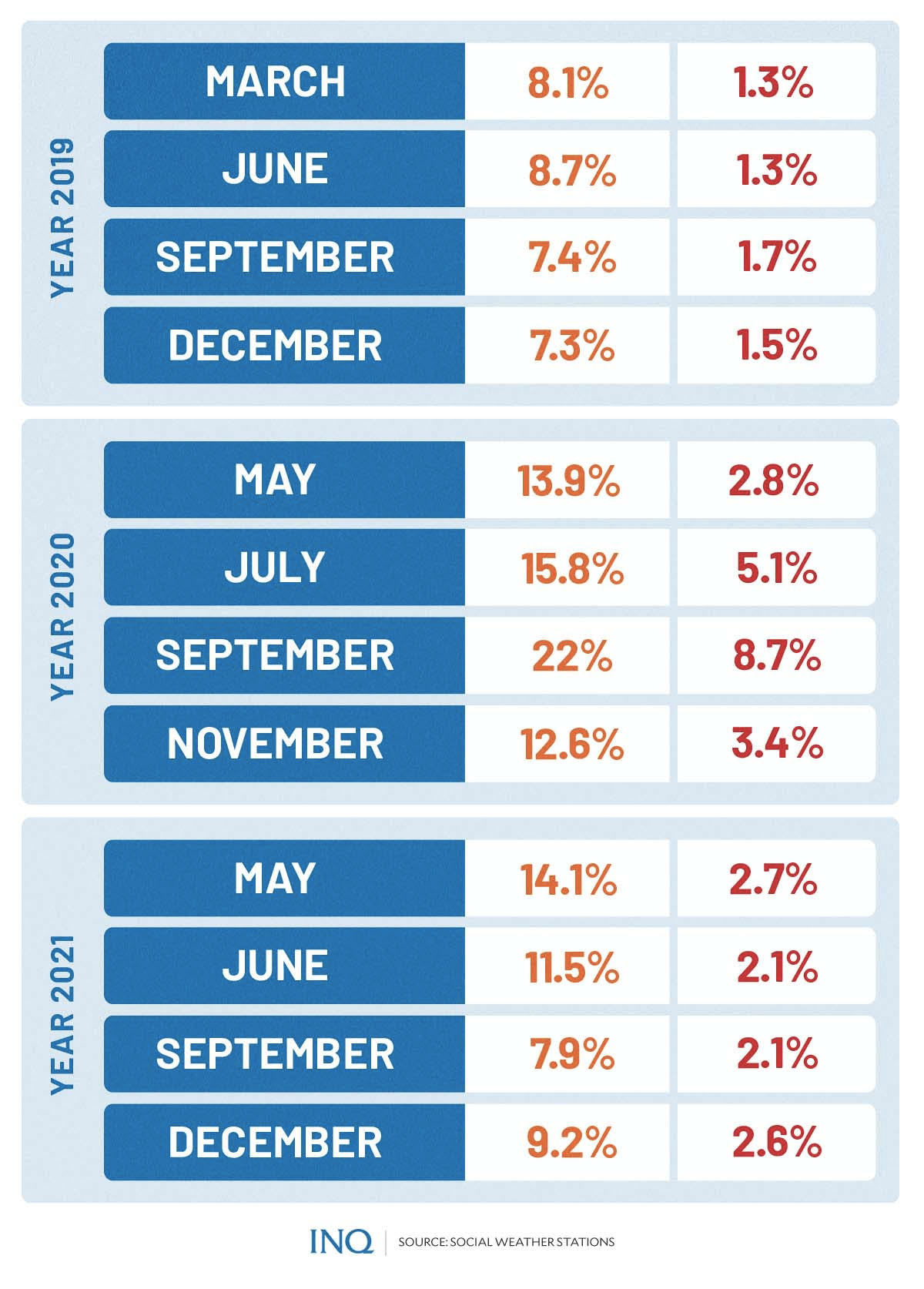

While hunger already fell to 11.8 percent in fourth quarter 2021, last year’s average—13.1 percent—was still well over the 9.3 percent average in 2019, which had been the lowest since 2004:

1998: 11 percent

1999: 8.3 percent

2000: 10.8 percent

2001: 11.4 percent

2002: 10.1 percent

2003: 7 percent

2004: 11.8 percent

2005: 14.3 percent

2006: 16.7 percent

2007: 17.9 percent

2008: 18.5 percent

2009: 19.1 percent

2010: 19.1 percent

2011: 19.9 percent

2012: 19.9 percent

2013: 19.5 percent

2014: 18.3 percent

2015: 13.4 percent

2016: 13.3 percent

2017: 12.3 percent

2018: 10.8 percent

2019: 9.3 percent

2020: 21.1 percent

2021: 13.1 percent

Prevalent

It was in 1998 (Q2) when the SWS decided to ask Filipinos regarding hunger as it saw the serious problem, especially in Mindanao, that year, Mahar Mangahas, president of the SWS, said.

Since then, household heads in Metro Manila, Rest of Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao, were asked regarding the experience of his or her family in the last three months.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The SWS said that in second quarter 1998, hunger was highest in Mindanao (15.3 percent). Mangahas said because the SWS was highly concerned by this, the polling firm decided to keep it on its “agenda” every three months.

Mangahas said SWS tracks the severity of hunger of a household from responses of household heads on how often they experience hunger or “had nothing to eat”.

The “moderate,” which indicates that hunger was experienced once or a few times, was high in third quarter 2020—22 percent of households:

2020 (Q3): 22 percent

2009 (Q4): 18.9 percent

2008 (Q4): 18.5 percent

2010 (Q1): 18.4 percent

2007 (Q3): 17.4 percent

2011: (Q4): 17.7 percent

2014 (Q3): 17.6 percent

2011 (Q3): 18 percent

2012 (Q1): 18 percent

2012 (Q3): 18 percent

The “severe,” which indicates that hunger was experienced often or always, was high in third quarter 2020—8.7 percent:

2020 (Q3): 8.7 percent

2001 (Q1): 6 percent

2012 (Q1): 5.8 percent

2000 (Q1): 5.4 percent

2013 (Q2): 5.4 percent

1998 (Q4): 5.3 percent

2008 (Q4): 5.2 percent

2020 (Q2): 5.1 percent

2000 (Q2): 5 percent

2012 (Q2): 4.8 percent

SWS, since second quarter 1998, already conducted 95 surveys on hunger, saying that in the last 24 years, the rate hit a record-low of 5.1 percent in third quarter 2003. Here are the instances when the rate was low:

2003 (Q3): 5.1 percent

1999 (Q3): 6.5 percent

2003 (Q2): 6.6 percent

2003 (Q1): 6.7 percent

2004 (Q1): 7.4 percent

1999 (Q1): 7.7 percent

1999 (Q2): 8.1 percent

2000 (Q3): 8.8 percent

2002 (Q3): 8.8 percent

2019 (Q4): 8.8 percent)

It was in quarter three 2020 when the rate hit an all-time high of 30.7 percent—22 percent (moderate) and 8.7 percent (severe). Here are the instances when the rate was high:

2020 (Q3): 30.7 percent

2012 (Q1): 23.8 percent

2008 (Q4): 23.7 percent

2009 (Q4): 23.4 percent

2013 (Q2): 22.7 percent

2011 (Q4): 22.5 percent

2014 (Q3): 22 percent

2007 (Q3): 21.5 percent

2011 (Q3): 21.5 percent

2010 (Q1): 21.2 percent

Poverty

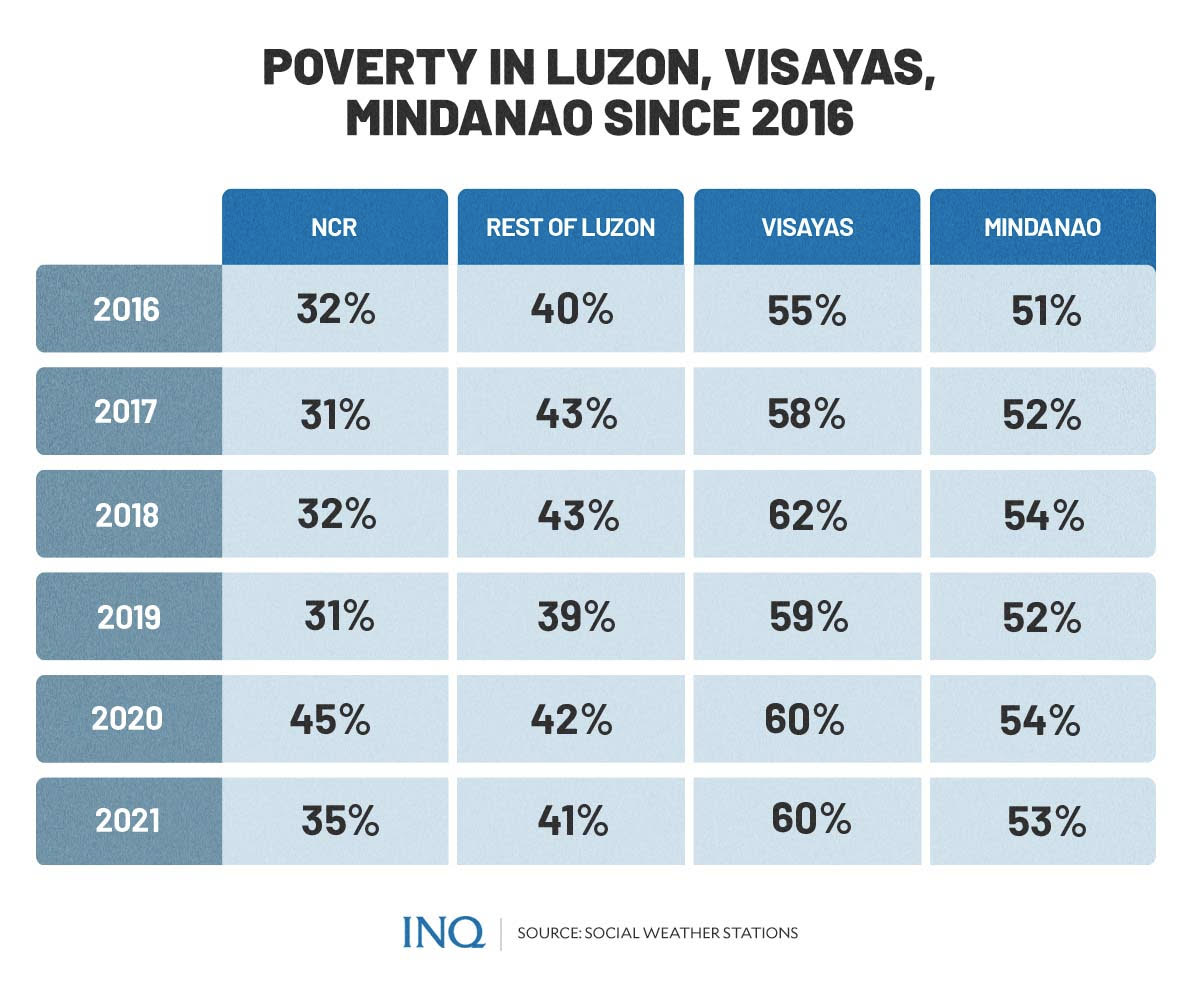

Mangahas said that while poverty and hunger are different, they are related, adding that not all of the poor go hungry, although it is more common for them to go hungry than those who rate themselves as not poor.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

As seen by INQUIRER.net, the rate of Filipino households considered as “poor” was high when severe hunger is prevalent:

November 1998: 59 percent

March 2000: 59 percent

April 2000: 60 percent

March 2001: 59 percent

December 2008: 52 percent

March 2012: 55 percent

May 2012: 51 percent

June 2013: 49 percent

November 2020: 48 percent

Mangahas said that from one quarter to the next, hunger rates, among both the poor and the non-poor, change.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

He said that from third quarter 2021 to fourth quarter 2021, hunger among the poor rose by over 3 percentage points, from 14.3 percent to 17.6 percent, while hunger among the non-poor rose by 1 percentage point, from 6.5 percent to 7.5 percent.

Mangahas said that out of the four SWS survey areas, Metro Manila often has the most hunger and the least poverty at the same time, explaining that families in the metropolis have much less opportunity to grow or raise their own food at home.

In quarter four 2021, Metro Manila had 22.8 percent hungry and 25 percent poor; the rest of Luzon had 9.2 percent hungry and 41 percent poor; Visayas had 9.7 percent hungry and 60 percent poor; while Mindanao had 12.2 percent hungry and 43 percent poor.