June 3, 2025

BEIJING – I first met Wang Fangting, better known as Liaoliao, at a sci-fi conference in Shanghai two years ago. She was a guest speaker, who, when stepping on the stage, apologized that she was so nervous that she had forgotten all she had prepared about her paper-cuttings, which seemed “remote from sci-fi or fantasy”.

About 10 minutes later, completely captivated by her “wonderland” shown in the presentation, I rushed to her seat, finding that she already started working on a piece of paper with scissors, a way she had practiced for years to vent negative emotions.

The next time when I saw that paper-cut piece — a two-legged star with a warm smile holding a smaller star before its chest — was at her debut exhibition, My Dear, Your Blossoms Are Scissor-Born in a village in Beijing’s Changping district in early May.

She greeted me at Lodge Kai ETA, an art gallery with a cafe where a part of the exhibits was presented. As she showed me around the space, her 9-year-old son came running to her from time to time, very much attached to his mother.

The exhibits that showcased her last 17-year efforts were displayed in two spaces. One was the dimly lit gallery and another a bright courtyard.

“In this gallery, it’s like back in my early days, when I felt enclosed and growing in the soil, painfully and with confusion. Here, I want to show that personal growing process,” said the 41-year-old artist.

“Then, I became a mother. I had to get out of the soil, connecting with the world, which actually started from my paper-cut illustrations for the book Yuefu. Those works are shown in the bright courtyard.”

At the gallery, the first interactive space was called Paper Shredder of Bad Moods. Visitors could write down or draw on paper whatever troubles them. Then taking the paper and a flashlight, one would walk through the entrance filled with 2-meter-long hanging thorns and snakes made of felt, seeing shadows of those thorns either growing like giants or shrinking on the walls.

Despite challenges from difficult people and events, there is always light filtering in, Liaoliao explained.

“And may we bravely find a path through the thorns that we can stick to.”

After passing through the thorns and snakes, one would come to a shredder.

“Scissors and knives have played a significant role to vent my emotions. You can write down or draw anything unhappy or sad, and throw it into the shredder to turn it into pieces of paper,” she said.

After the exhibition, Liaoliao will reshape the paper shreds into a sculpture.

She then led me into a dark room. She clicked on a button and suddenly the room became a world of fantasy. Groups of small paper-cut figures stood hand in hand on a big table. Most of the figures were white, and some were vivid red, blue and yellow. Varying in forms — ghost, dinosaur, radish, rabbit, or skeleton — they appeared lost, sad, angry, curious or happy.

In the middle of the table was an elliptical trail. Two closely set lighting devices were moving on the trail. Each lighting device had two opposite spotlights so that as they traveled, the shadows of the figures grew or shrunk as if coming to life, especially accompanied by bird chirping sounds.

I was amazed just like two years ago.

A work of the Alice series. PHOTO: PROVIDED/CHINA DAILY

Spark of inspiration

Liaoliao started telling me those figures’ origin. Long before she ever began paper-cutting, there was a time in her early 20s when she would sketch on tiny paint boxes.

“Back then, I felt lost and was in pain, so I drew small, colorless figures curled up alone, hugging their knees, everywhere. Sometimes they were happy and sometimes they were crying. And the crying figures looked very real. They had no color because they were hollow inside, hopeless,” she said.

Around 2008, she hardly went out, living in a reversed day-night cycle, passing long nights with nothing to do. One day, with paper and scissors in hand, she folded and cut the paper much like she did in childhood. When she unfolded it, that small surprise lit a spark.

“Compared to other forms of expression, I appreciate its cleanliness and purity, enjoying the decisiveness and choices made with each cut,” she said.

In 2012, she had these figures stand up.

“They are my buddies,” she said, pointing at them. “Initially, it was just me, all alone. But then, one by one, I started making friends — little buddies to hold hands with. It’s like I finally found a way to connect with the world. Paper-cutting is my way to connect with the world.”

Outside the dark room, visitors could see Liaoliao’s other early works, including those inspired by the classic tale of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

In the finely cut details of Alice series, one could see the smiling face of the Cheshire Cat, the freckles on the face of the caterpillar, the evil-eyed Queen of Hearts playing croquet holding in her hands a flamingo that shuts its eyes tightly, ghostlike rabbits, piled teapots, as well as countless plants and other elements from the story. Alice always wore black circles around the eyes.

“That’s because I always stayed up late back then,” she said, smiling.

Raised in Chongqing, Liaoliao, once timid and self-doubting, grappled with parental critiques on her looks, which made her doubt her own abilities.

At 16, before graduating from senior middle school, she became so rebellious that she decided to quit school and went to Ukraine to study Russian and oil painting.

One year later, without learning much, she returned to China, started fumbling on the way of art creation, until coming across paper-cutting.

Over the years, China Post, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and BBC among others have become her clients. She also did the paper-cut illustrations for 14 books by Cao Wenxuan, winner of the Hans Christian Andersen Award in 2016.

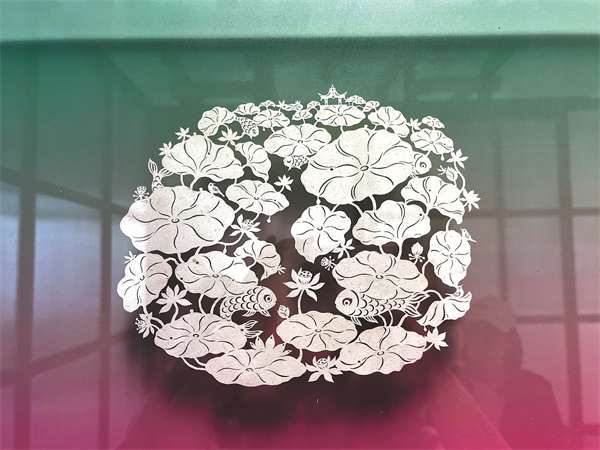

Jiangnan presents a vivid illustration of lotus leaves. PHOTO: PROVIDED/CHINA DAILY

Broader perspective

At the exhibition, there were two owls she created at different stages. The one with feet resembling those of a cat was one of her early works.

She was inspired by a visit to the National Museum of China in Beijing in 2011, where she saw an eagle-shaped pottery vessel from Yangshao Culture (a key Neolithic culture dating back 5,000 to 7,000 years across the northern part of China). “The eagle’s feet drew me out of Western aestheticism,” she recalled.

Another owl she created earlier this year had a pair of sharp claws.

“The previous owl is gentle like in a fairy tale, but this one may bite people,” she said, adding that she created the latter owl during a period when she fiercely defended her son from being bullied at school.

“I’ve changed a lot in the past two years. As I get more experience from different projects, I realize that I can do so many things. I did many things for this exhibition.”

Her eyes glistened.

In the Pomegranate Courtyard, Liaoliao exhibited her later works. An important part was those she created for Yuefu, a poetry collection featuring works from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) to the end of the Six Dynasties period (from the 3rd to 6th centuries).

Creating illustrations for the ancient poems gave her a chance to walk out of self-expression and to think about how to translate the poetic lines into the paper-cut language, how to represent the clouds, the wind, the water or a psychological state in a language she found little reference in the books about traditional Chinese paper-cuttings she had read, she said.

In Yuefu, there is a poem titled Hao Li, which in ancient times meant a place where people’s souls lived after death.

“I worked really hard on this work. It used to be fancy with ghosts spiraling upward, but it didn’t match the poem’s mood — a peaceful, somewhat distant feeling in a place filled with souls,” she said.

In the second version, she drew a big tree in the middle and two little cute ghosts sitting on it. It was too lively, neither right, she said.

“This is the third version. I cut all unnecessary elements, trying to be accurate,” she explained.

“While I made these works, it’s like I was having cross-temporal dialogue with ancient people.”

Chen Lingyun, editor-in-chief of publishing company Cuneiform in Beijing, was among the first visitors to the exhibition.

His first encounter with Liaoliao’s paper-cutting was one piece depicting a carp holding up clouds with a small pavilion on top.

“I felt the charming simplicity in her work, different from the folk style of traditional paper-cutting,” he said.

When he saw her works for Yuefu, he felt her works “resonated with the archaic innocence of those ancient verses while retaining her own delicate ingenuity”, he said.

Apart from the carp piece, he was particularly fond of one named Jiangnan, an illustration for a poem of the same title, in which she depicted the line “lotus leaves everywhere, fish playing among them”.

“The entire work portrays a sea of lotus leaves with varying sizes, lotus flowers, and swimming fish, seemingly endless yet simple and direct, which I really like,” he said.

“Paper-cutting often gives a fragile impression, but Liaoliao’s precise knife work endows her pieces with a simple and resolute quality akin to Han Dynasty stone carvings,” he added.

Visitors get hands-on experience on paper-cutting at the show. PHOTO: PROVIDED/CHINA DAILY

Return to self-expression

The last part of the exhibition included her latest works created for a project about the mythic geography book Shan Hai Jing (The Classic of Mountains and Seas), for which she had spent two years reading materials and watching documentaries to study the physical structures of animals like lizards.

Although the project was canceled, Liaoliao did not give it up. Instead, she found it a great opportunity to return to self-expression. She aspired to use her art language to represent the aestheticism and spirits of the time, but the key issue she needs to solve is to create signature images, “just like those we see in Chinese animated movie The Legend of the Sealed Book”, she said.

In a work called Mountain Spirit II from The Classic of Mountains and Seas, which is an image of a spirit with a snake’s body and boy’s head, delicate hollowed lines made the body muscular.

“The paper-cutting language is the cutout spaces on flat paper. It’s just a two-dimensional sheet. Yet, with the cut-out hollows, you need to convey power, hope, emotions, even pure aesthetics. For example, this mountain spirit. When people look at it, they can feel the twisting motion of a snake because of the cut-out lines,” she said.

“It’s really challenging. What’s easily achieved in painting becomes a puzzle in paper-cutting.”

Stopping before the Mountain Spirit I that shows a bird-body human-head spirit, Liaoliao explained that she wanted to use paper-cutting language to represent a divine state like what stone carving can do. With these works, she was approaching her goal.

“What I really want is for every deity from The Classic of Mountains and Seas to have their own distinct presence and state,” she said, adding that she will continue working on this series in the following couple of years.

“These are just the beginning.”